My favourite painting: Michael Billington

Michael Billington chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

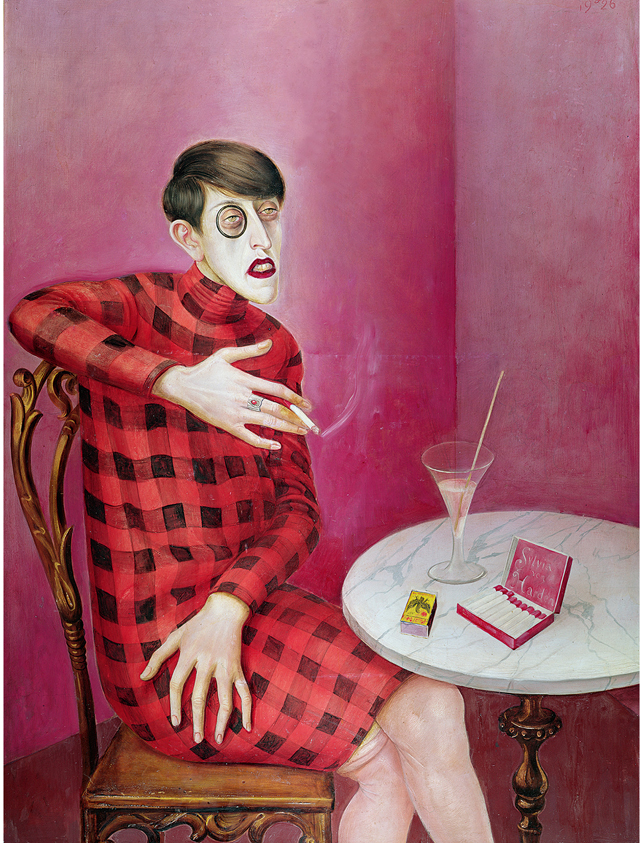

Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden, 1926, by Otto Dix (1891–1969), 471⁄2in by 35in, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Bridgeman Images.

Michael Billington says: I’ve been haunted by this painting ever since I first saw it in a Paris museum. It’s not just because it’s a portrait of a journalist, although there can’t be many of those in art history. There’s something about this woman’s mannish hairstyle, monocle and steely gaze that seems to sum up Berlin in the 1920s. It’s a world that has always fascinated me, whether through the plays of Bertolt Brecht, the music of Kurt Weill or the novels, now increasingly popular, of Hans Fallada. The decadent glamour of the period inspired a furious creativity and savage satire. For me, that’s all summed up in a portrait that, once seen, is never forgotten and that tells you all you need to know about this louche observer of the passing scene.

Michael Billington is Country Life’s theatre critic. He will be bringing out a book about the plays of Shakespeare this autumn.

John McEwen comments: For centuries, German artists have shown the world in warts-and-all reality. After the First World War, the tendency was expressed as an art movement, Neue Sachlichkeit (New objectivity or Matter-of-Factness). Otto Dix was a leading exponent of the style, exemplified by this portrait.

Sylvia von Harden was born von Halle. She changed her name to sound grander when starting as a journalist for the postwar Das Junge Deutschland. Unisex haircut, monocle, American cocktail, Russian cigarettes (inscribed with her name) all proclaim the new, emancipated woman. It remained scandalous to smoke, the public habit in peacetime only excusable for upper-class men and labourers.

In 1959, von Harden wrote an article, Memories of Otto Dix, in which she recalled the chance meeting in the street that led to the painting: ‘I must paint you, I simply must!... You are representative of an entire epoch.’ ‘So, you want to paint my lacklustre eyes, my ornate ears, my long nose, my thin lips; you want to paint my long hands, my short legs, my big feet—things which can only scare people off and delight no-one?’ ‘You have brilliantly characterised yourself,’ said Dix.

Realism in German art, and especially in that of Dix, famous for his pitiless pictures of war and its crippled victims, is equated with ugliness. But not by him. In old age, he said: ‘I wasn’t trying to depict ugliness at all. Everything I have seen is beautiful.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Dix died lauded in both Germanys; von Harden, best remembered for her portrait, died an exile in Croxley Green, Hertfordshire.

This article was originally published in Country Life, April 29, 2015

More from the My Favourite Painting Series

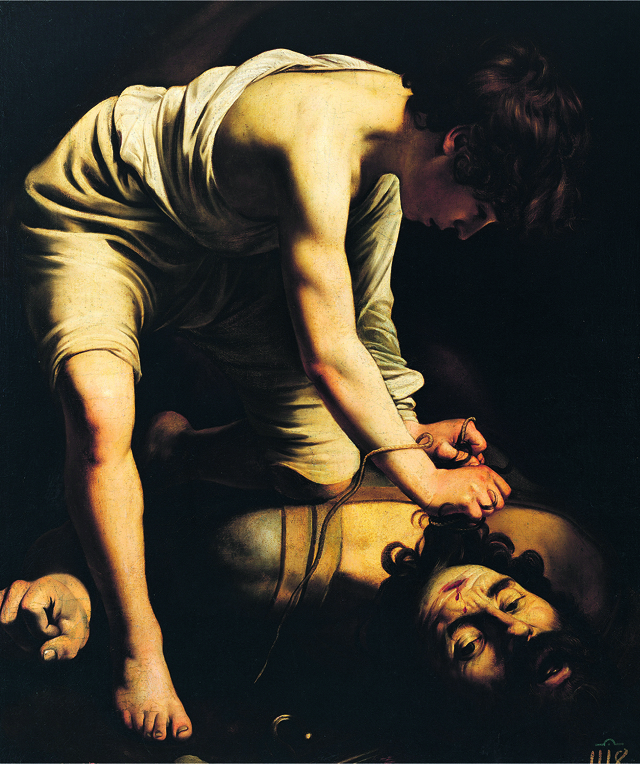

My favourite painting: Dan Pearson

Dan Pearson chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

My favourite painting: Fiona Bruce

Fiona Bruce chooses her favourite painting for Country Life.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.