In Focus: The Hogarth masterpiece which shows that sometimes you need to 'listen' to a painting

A small exhibition at the Foundling Museum focuses on one painting — an image that inspires Huon Mallalieu to reflect on Hogarth’s enthusiastic orchestration of sound.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Seven years ago, I argued in Country Life that we should often listen to paintings as well as look at them. From the 15th century onwards, many painters have worked to insert sounds into our minds as well as colours, images and stories.

What I called ‘the conscious manipulation of our imaginations through suggested sound’ is particularly evident in late-16th- and 17th-century Flemish and Dutch art, but it continues, through Courbet, who said that he wanted people to hear the deer moving in his woods and his rollers crashing onto the shore, to Maggi Hambling, who similarly wants us to hear her waves breaking on the Suffolk shingle.

At first, as with Bosch’s literal instruments of torture, suggested sounds made the painter’s intentions clear to illiterate audiences, who ‘heard’ the hellish dissonances or heavenly choirs. Later, contemporaries of such specialists in music-making scenes as husband and wife Jan Miense Molenaer and Judith Leyster may well have been able to tell what tunes and songs were being performed from painted gestures and props.

At the time of my article, I thought that the more overtly loud a subject — say a railway station by William Powell Frith or a cavalry charge by Lady Butler — the more difficult it might be to listen to what we see.

Too much noise could overwhelm the individual sounds. However, this small display at the Foundling Museum, focused on William Hogarth’s The March of the Guards to Finchley, brings the crowded canvas to raucous life.

It was painted in 1750, five years after the events that inspired it — the chaotic response to Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s march on London during the ’45 Jacobite rebellion.

The action is set on the northern edge of London, where the Tottenham Court Road ran into the country. In the foreground, a milling crowd is studded with drunken and lecherous soldiers, who are mostly reluctant to follow their more disciplined brethren already on the march.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

They are attended by all the low-life of the city: prostitutes, ballad-mongers, pugilists, pickpockets, tricksters, piemen, spies and many more. Mother Douglas, the leading bawd of the day, has moved her girls from Covent Garden to service the occasion from a convenient house.

The central group of a grenadier beset by two women, one pregnant and selling sheets of the Hanoverian God Save the King, the other belabouring him with one of her pamphlets, has been interpreted as the tug of divided loyalties.

However, there may be more to be said, as at least one of her pamphlets was anti-Stuart, despite being labelled The Jacobite’s Journal. This was the title of a Hanoverian satire produced after the rebellion by Hogarth’s friend Henry Fielding and deployed as government propaganda.

A soundscape commissioned from the musician and producer Martyn Ware leads us through the throng, highlighting and interpreting the incidents and allusions and revealing ‘how Hogarth orchestrated the natural and man-made sounds of London, to capture the vibrancy and complexity of 18th century life’.

A valuable accompaniment to the main display is a number of alcoves in which headphones, wall-based interpretation and engravings are used to delve deeper into topics and contexts.

On my visit, I coincided with a class of schoolchildren, who were naturally enthused by the performance. This reminded me that, when I wrote about the subject in 2012, I was told of an inner-city class that was asked to describe what it had seen on a visit to the National Gallery. As one child, they responded with the noises they had ‘heard’ in favourite paintings.

In this spirit, it would have been valuable had there been room for a second display here of another ‘noisy’ painting or print — perhaps The Enraged Musician — with a challenge to people to sit in silence with it and note down all the sounds that it made them hear in the mind’s ear.

‘Hogarth & The Art of Noise’ is at The Foundling Museum, 40, Brunswick Square, London WC1, until September 1 — www.foundlingmuseum.org.uk

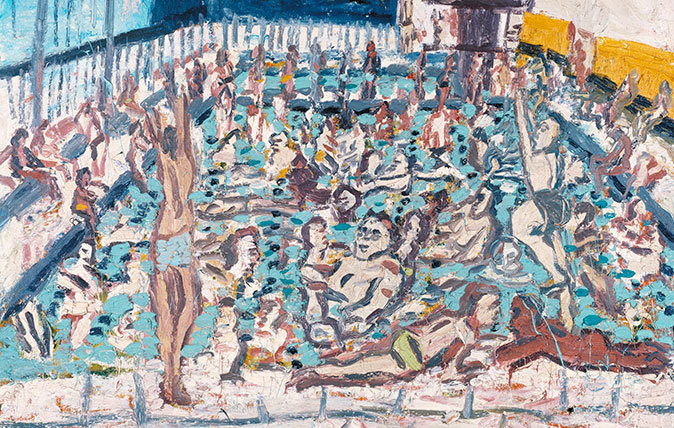

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

Credit: A British countryside image by Paul Sandby RA, courtesy of the Nottingham City Museums & Galleries

In Focus: The 'jobbing artist' who pioneered new technology and defined countryside painting as we know it

The landscape artist Paul Sandby divided critics even within his own lifetime, but what he left behind is an honest

In Focus: Bomberg, the trailblazer who led the way for modern British art but died an impoverished war veteran

Coinciding with the sixtieth anniversary of the artist’s death, the touring exhibition of David Bomberg’s work is entering its final

After four years at Christie’s cataloguing watercolours, historian Huon Mallalieu became a freelance writer specialising in art and antiques, and for a time the property market. He has been a ‘regular casual’ with The Times since 1976, art market writer for Country Life since 1990, and writes on exhibitions in The Oldie. His Biographical Dictionary of British Watercolour Artists (1976) went through several editions. Other books include Understanding Watercolours (1985), the best-selling Antiques Roadshow A-Z of Antiques Hunting (1996), and 1066 and Rather More (2009), recounting his 12-day walk from York to Battle in the steps of King Harold’s army. His In the Ear of the Beholder will be published by Thomas Del Mar in 2025. Other interests include Shakespeare and cartoons.