Peacocks: Everything you need to know about 'the limousine of the avian kingdom'

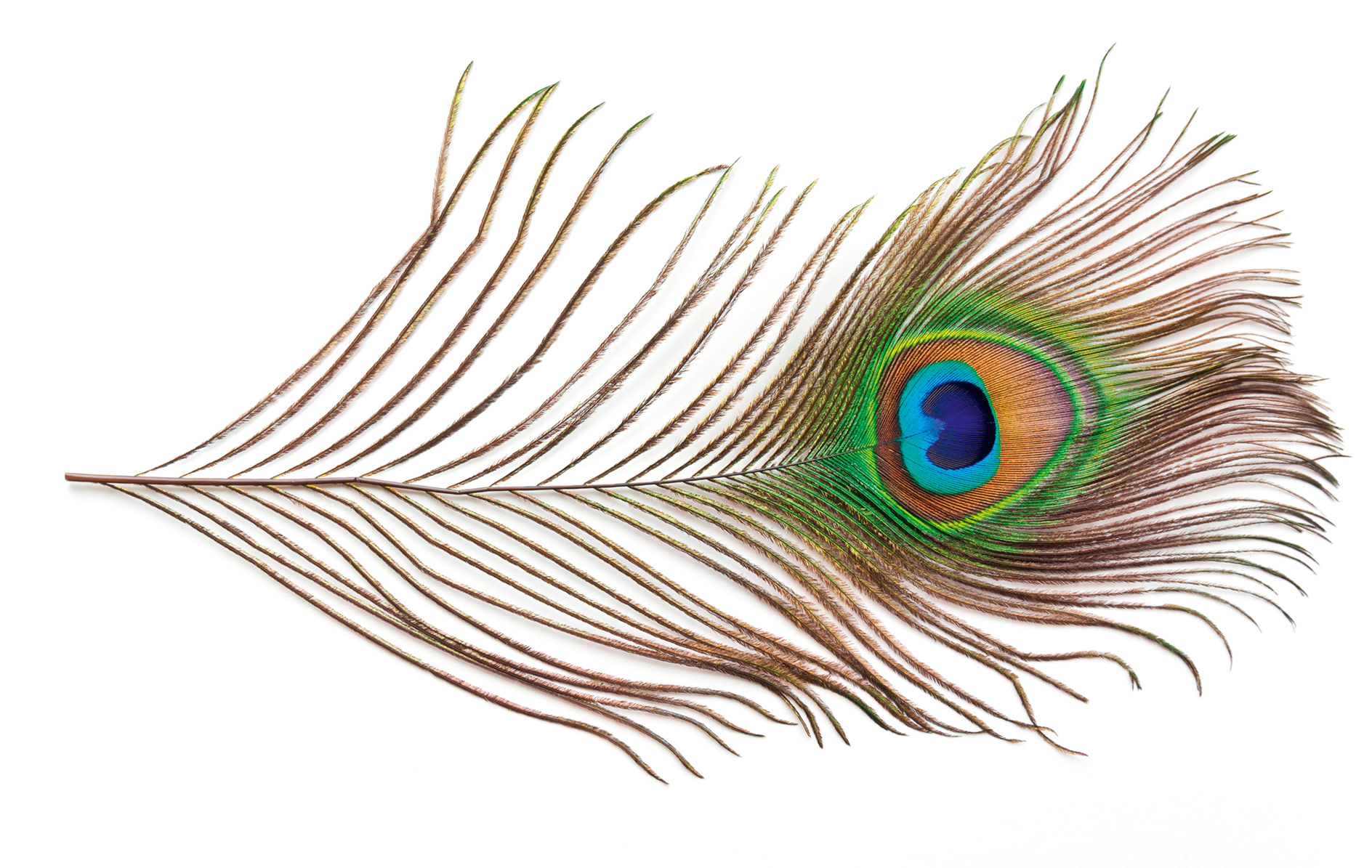

Graceful peafowl have never been shy about coming forward, although most of us admire the males’ flamboyant tail feathers — long a vibrant and striking motif — far more than their grating cries, says Harry Pearson.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With the imperious upturned head and rustling walk of an Edwardian dowager duchess, the peacock is the very emblem of elegant rural existence.

The bird’s exotic radiance fits as reassuringly into a world of croquet lawns, terraces, topiary and ha-has as the russet feathers of other long-ago imported gamebirds do in our meadows and copses.

Yet, although we have grown accustomed to its presence, the peacock retains an air of exclusivity. It is a polished, ornamented and expensive version of its cousin the pheasant — the limousine of the avian kingdom.

Keeping peacocks: what you need to know

- Peacocks are categorised as livestock rather than wildfowl, which means that the owner is responsible for any damage they cause to gardens or property

- Peacocks are noisy and are not suitable for residential areas. If statutory noise-nuisance complaints are upheld, owners can be subject to legal action

- Ideally, you should keep one male and four to five females

- Peacocks have little traffic sense and need to be kept away from roads

- They must be acclimatised to their surroundings by being kept in a pen for about six weeks. If they are let loose before then, they are likely to disappear

- Originally from Asia, peacocks do not like cold, wet weather and need somewhere to shelter

- Ground-nesting females are vulnerable to attacks by foxes

Why do peacocks show off their tails?

Even the bird’s sworn enemies cannot deny that the peacock is spectacular. His habit of flipping open his tail feathers as a flamenco dancer does her fan is one of the wonders of the natural world. Clearly, the peacock is doing it to attract the dowdy peahen, but how he does it is a matter of keen debate.

Some naturalists believe it is all about the vibrations — once he’s unfurled his feathers, the peacock flutters them at about 24 times per second. The resulting airwaves set the crest on top of the peahens’ heads vibrating. She knows the male is around even before she sees him and, from the force of the vibrations, can tell exactly how long his tail feathers are. And that is important, because it seems that, for the peahen, size really does matter.

Another school of thought is that the eye-catching spots on the peacock’s tail feathers look to the myopic peahen like some succulent grape or blueberry. The longer the feathers, the more berries the peacock is offering. Perhaps he is simply luring the female with the promise of a nice supper?

The unwieldiness of the tail feathers is an example of the handicap principle of sexual selection. As the alpha male gorilla lies down and bares his chest and throat to the world, so the peacock signals his self-confidence by reducing his ability to flee with a lot of pointless flummery. Demonstrating that you are fearless can be attractive to females: it is why boys buy motorbikes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

How peacocks came to Britain

The peacock’s journey from its native India to the grounds of the British country house was long and convoluted. It started, perhaps, with Alexander the Great. When the Macedonian king first saw peacocks on the banks of the River Ravi in the Punjab, he was so astonished by their iridescent beauty he thought they must be divine and — as he was descended from a God himself — some sort of distant relation. Alexander ordered the birds protected and sent some back to Greece.

Although Phoenician traders probably brought peacocks to Europe some 600 years before Alexander, it was the charismatic conqueror who popularised them. His tutor Aristotle also played his part in the peacock’s voyage to our shores. The great philosopher conceived the idea that the peafowl’s flesh did not corrupt after death. This misplaced belief led to the bird being associated with immortality and the resurrection. As a consequence, it became an early symbol of Christianity. The catacombs of Rome were decorated with images of peacock feathers. Word of the bird spread as missionaries travelled westward.

Muslims took a different view. To them, the bird was vain and evil. Its shrill keening a curse from the Almighty — punishment for having helped the Devil slip into the Garden of Eden. That is the public perception of the peacock in a nutshell. For one person, the bird is a heavenly creation whose pride, as William Blake noted, ‘is the glory of God’. To others, it is a satanic menace that keeps entire communities awake at nights, rips the roofs off garden sheds with its sharp claws and destroys flowerbeds in its greedy quest for food.

Whatever the principles underpinning the display, the tail feathers proved almost as attractive to people as they did to peahens. They were so sought after and so widely traded in the Dark Ages that, by the 9th century, they could be found as far apart as Osaka and Oslo.

The first mention of the bird in England comes shortly after the Norman Conquest, although it’s hard to believe successful Romans — who took ostentatious delight in serving peacock at banquets, largely because the birds were so expensive — hadn’t imported a few to our shores long before that.

By the 14th century, the peacock was sufficiently well known in England to feature in Chaucer as a symbol of strutting vanity. Like Alexander, English knights took a more positive view. They were inspired by the bird. They took ‘the peacock vow’ and decorated their helms with the bird’s feathers. In Elizabethan times, the courtly swishing movements of the peacock gave rise to a dance craze called the ‘pavane’, derived from pavón, the Spanish word for peacock.

Can you eat peacocks?

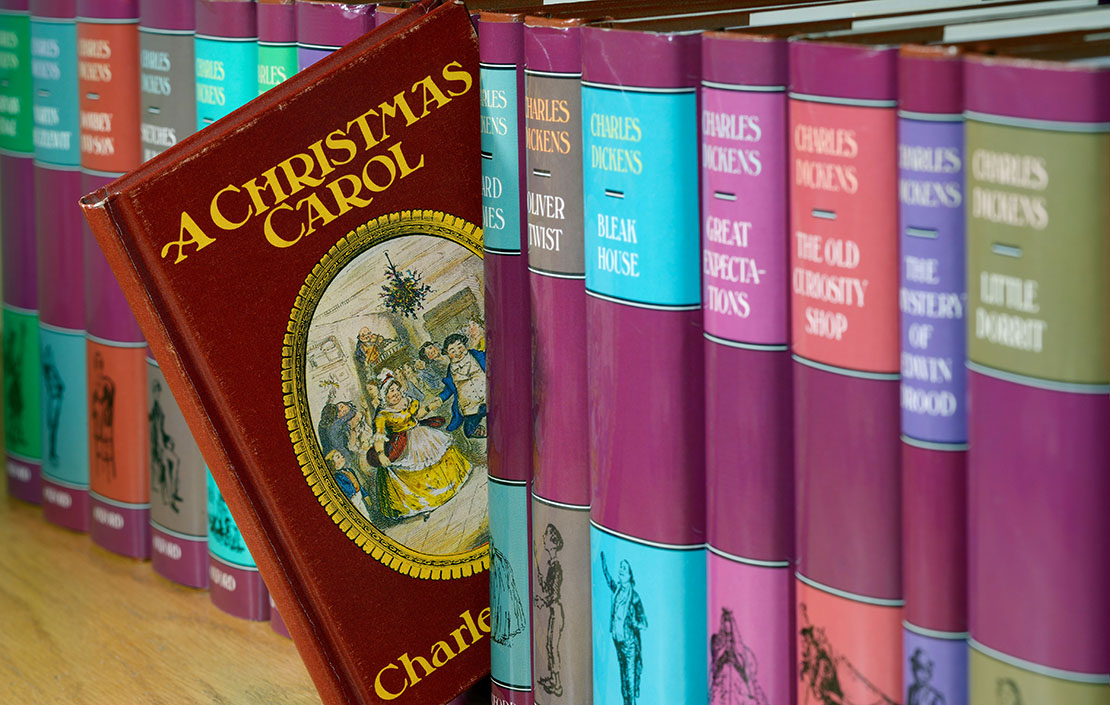

The peacock’s association with English country houses began in the Middle Ages. Most likely this was because, like white doves, the peacock was a colourful addition to the garden that could be eaten in winter when game was scarce. Peacock pie was a Christmas delicacy in medieval England — despite reports that suggest the meat was tough and coarse and physicians believing it was indigestible and unbalanced the humours.

Despite such concerns, people carried on eating the bird, generally roasted and carried to the table on a bed of its own feathers.

By the 18th century, when peacocks imported by the East India Company became fashionable, the peacock was ornamental and rarely eaten. One of the last recorded meals of roast peacock was served in 1914, at a luncheon held by poets W. B. Yeats and Ezra Pound at Crabbet Park, West Sussex, the home of Arabian-horse breeder Wilfrid Blunt. Perhaps it is a sign that the caterers, marshalled by Augusta, Lady Gregory, had little confidence in the savour of the gaudy fowl that roast beef was also on the table.

How the pre-Raphaelites became obsessed with peacocks

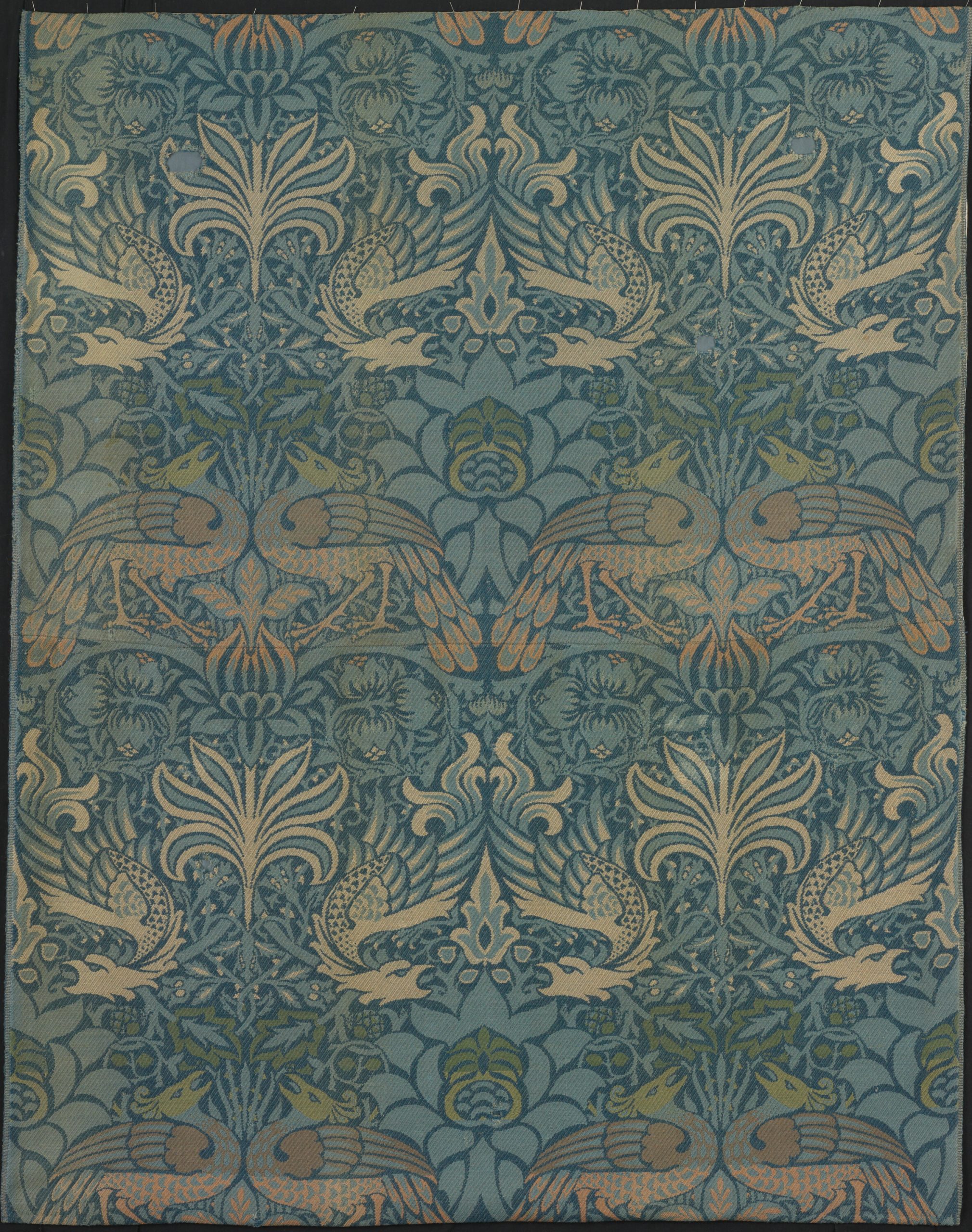

Blunt and his wife, Lady Anne, had once moved in Pre-Raphaelite circles and, given this group of artists’ penchant for colourful romanticism, it’s no surprise to learn that peacocks fascinated Dante Gabriel Rossetti so much that he kept one as a pet at his house in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. It irritated the neighbours so much that the ground-landlord, Lord Cadogan, subsequently banned residents from keeping the birds, but, inspired by it, Rossetti’s friend, William Morris designed his celebrated Peacock & Dragon fabric for Liberty in 1878.

A year earlier, James McNeill Whistler’s enchantment with Rossetti’s bird had resulted in him designing the green, blue and gold Peacock Room in the Kensington home of Frederick Richards Leyland. Alas, so garishly over-the-top was the interior, Leyland flew into a rage at the sight of it and refused to pay the fee the American artist demanded.

The legal wrangle over payment plunged Whistler into bankruptcy and his co-designer, Thomas Jeckyll, suffered a nervous breakdown. The US painter was not the first person to be bedazzled by the beauty of peacocks, nor would poor Jeckyll be the last to be driven to distraction by them.

Topiary: The ancient art of transforming nature into cubes, pyramids and peacocks

A celebration of pheasants, 'some of the most beautiful birds in the world'

We tend to think of pheasants as a relatively ordinary sight, but they're among the world's most beautiful birds — and

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Jason Goodwin: 'His novels tend to involve a party of opinionated conversationalists descending on a remote country house to talk, drink, dispute and fall in love'

Jason Goodwin tells us about his latest collaboration with graphic designer Richard Adams: a bound and illustrated Christmas story for

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.