Plasterwork perfection contained within an unassuming Devon farmhouse

The ornate plasterwork of the 17th century reached a high-point in the West Country, as Roger White discovers at the delightful Rashleigh Barton.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For much of its history, Rashleigh Barton has been a modest farmhouse. It sits in rolling countryside above the west bank of the River Taw, across the valley from the little town of Chulmleigh (although it is invisible either from it or indeed any road). The river flows northwestwards to the much more important town of Barnstaple, some 15 miles away, and the main road connecting Barnstaple to the regional centre of Exeter follows its course.

The Rashleigh family originated in Barnstaple, but were in possession of this property by 1196. In 1530, the Rashleigh heiress Ibbot married Thomas Clotworthy from South Molton and, although the Rashleigh name stuck, the estate became a Clotworthy possession until 1708, when it passed by marriage to the Tremaynes of Heligan in Cornwall.

The Tudor Clotworthys found themselves in possession of a late-medieval house built of cob. As is characteristic of Devon, it was long and low with a double-height hall incorporated in the centre of the plan. This was entered through a tall porch – in the position of its low, modern successor built in 1999 after the original had been lost – and warmed by a fireplace with a massive chimneystack, both typical architectural features of the region.

At one end of the hall (to the south), there was a screens passage and, beyond that, the kitchen and buttery, with accommodation above.

The hall itself was spanned by a roof – still surviving and partially visible – with multiple tiers of windbraces, a treatment that, through its greedy consumption of timber, emphasised the wealth of the house’s owners. In a cross wing at the opposite end were the principal family chambers arranged on two floors.

It is presumed that, during the 16th century, one of the early Clotworthys – either Thomas and Ibbot’s son Thomas or their grandson Simon – introduced a floor into the hall, creating new domestic rooms in its roof space that linked the first-floor chambers at the two ends of the house. Such reorganisations of medieval hall interiors are a commonplace of the Tudor period. In the process, the partition closing off the screens passage was replaced with a wall pierced by a single door.

Of the Tudor decoration of the house, we know little, because, in the 1630s, during the tenure of John Clotworthy, its interiors were reordered and overlaid by the sumptuous plasterwork that is the modern glory of Rashleigh Barton.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Externally, Rashleigh Barton’s modest size and plain, whitewashed walls do little to raise expectations of an exciting interior (Fig 2).

The porch leads into a corridor, the successor to the screens passage. To the right (south) lay the original kitchen and services. Access to the room above it was provided in the 1630s by a stair turret and external gallery.

The latter (Fig 3) is now internalised by the addition of new kitchens, probably in the 19th century, to the rear of the hall.

At the time of this addition, the original services were completely reconfigured to create two comfortable rooms, one of which was a cosy, oak-panelled winter parlour. The parlour joinery, complete with Clotworthy arms over the fireplace and a frieze of firebreathing dragons, may be partly recycled from elsewhere in the house. To the south again, the Clotworthys added a granary range, never directly accessed from the house.

Across the passage from the winter parlour, a door opens into the hall, a singlestorey room with a simple beamed ceiling and an even simpler granite fireplace, probably of Tudor or late-medieval date (Fig 4).

By the early 17th century, the hall had ceased to function as a dining chamber in gentry houses, although it remained one for servants.

This probably explains why at Rashleigh Barton no particular effort was made to introduce fancy decoration here. Rather, it was concentrated on the withdrawing spaces beyond and accessible through a door at the opposite end of the room from the entrance passage.

The ground-floor parlour was where the family could meet, talk, relax informally and sometimes eat (Fig 1, at the top of this page). Above it was the great chamber, which was for all formal entertaining, including dining, music and dancing.

The parlour has a flat ceiling divided by deep, plaster-clad beams into three oblong compartments. At the centre of each is a shield of Clotworthy heraldry (Fig 7), out of which elaborate foliage trails loop and intertwine across the remaining surface.

The curlicues sprout hops, pears, pomegranates, apples and different flowers and the intervening spaces are occupied by such creatures as elephants, camels, lions, boars, pegasuses and cockatrices, not to mention birds, butterflies and assorted bugs. The design and modelling are not sophisticated, but are immensely endearing.

To connect this upgraded parlour with the yet more elaborately decorated great chamber above it required a suitably handsome staircase, which was provided in a new projection at the north end of the wing. This rises to a landing enclosed by typically Jacobean elongated column balusters (Fig 5). The vestibule at the top of the stairs – an antechamber to the great chamber – suffered badly during the long years of Rashleigh Barton’s neglect, when much of the ribbed barrel vault collapsed (Fig 8).

However, the tympana of the end walls retain their elaborate strapwork cartouches centred on Clotworthy heraldry, with putti perched nonchalantly on the extremities and, in one of them, the initials ‘IC’ (for John Clotworthy) and ‘MC’, together with the date 1633. Visitors would have seen this before passing through the door beneath into the richly embellished great chamber that was the climax of the Jacobean interior.

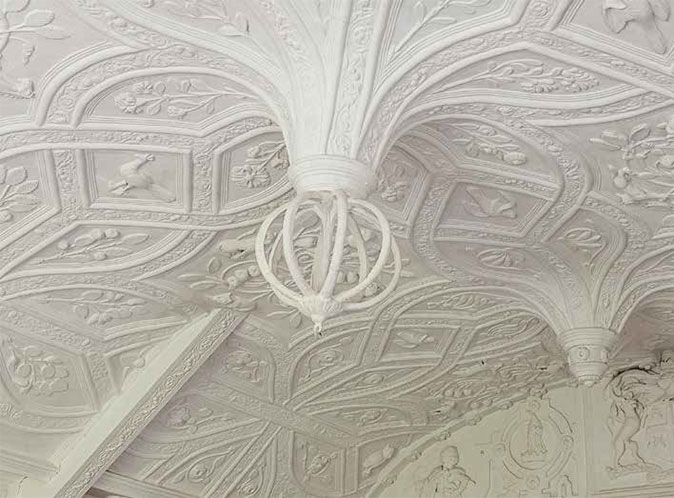

The chamber walls are bare – no doubt, originally, there would have been hangings or panelling to conceal them – and the crudity of the fireplace opening suggests that a more elaborate affair, possibly with overmantel, is missing. The decorative effort is all now concentrated on the ceiling, a barrel vault that has clearly been superimposed on the earlier medieval rafters (Fig 6, above).

The latter protrude somewhat awkwardly through a dense web of ribs that curve, intersect and interweave like the pattern of a particularly elaborate knot garden. Many of the resulting compartments are, in fact, filled with stylised sprigs of flowers and it is indeed known that the patterns of such Elizabethan and Jacobean ceilings were often inspired by what went on in the garden.

The four largest compartments are concavesided octagons and these are occupied by foliage tangles of exactly the same varieties as the parlour below: apples, pears, hops and pomegranates. Paired with these are quartets of animals – foxes, dogs, lions and unicorns respectively. Even this does not exhaust the profusion of motifs, which also feature goats, rams and birds (including a peacock and a dopey owl). All this arranges itself around three pendant bosses, the central one in the form of an openwork cage.

The ensemble is completed on the inner wall with arms said to be those of William Bourchier, 3rd Earl of Bath, although, as he died in 1623 and the plasterwork here is probably a decade later, they perhaps refer to his eldest son Edward, the 4th Earl. The Bourchier seat was at Tawstock Court near Barnstaple and John Clotworthy was presumably a protégé who aspired to entertain his powerful patron at Rashleigh Barton.

The question that obviously presents itself is who the author of this display of rustic virtuosity in plaster might have been. The existence of the Abbott family from the village of Frithelstock, a north Devon ‘dynasty’ of plasterers going back to the late 16th century, has been widely accepted since the publication in 1940 of a Country Life article by Margaret Jourdain. This focused on a surviving sketchbook full of what, on the face of it, looked like Elizabethan and Jacobean motifs, seemingly compiled by one John Abbott, born in 1639.

It was thought at one time that the sketchbook was a testament to the longevity of a stylistic vocabulary that had long gone out of fashion elsewhere, passed down through generations of Abbotts.

In fact, the dates occurring in the plasterwork at Rashleigh Barton make Abbott’s involvement here impossible and, in any case, there are no similarities with Abbott’s documented work, which is dated to the 1680s and in the characteristic idiom of Charles II’s reign.

Subsequent writers drew attention to Abbott’s grandfather, also John, who died in 1635 and may have been the first of the family to take up the profession, or his father Richard, born in 1612.

More recently, doubt has been cast on the very existence of an Abbott dynasty, as there is no direct evidence to confirm the identity of any plasterers in the region prior to the mid 17th century. However, even if the Rashleigh plasterwork cannot be by John Abbott the younger, the nearness of the estate to Frithelstock does at least allow the possibility of involvement by his elderly grandfather or youthful father.

There does, in any case, seem to be a definite overlap in both idiom and motifs between the Rashleigh great chamber and the ceiling of a house in Boutport Street, Barnstaple, dated 1620. There also are also comparisons to be made with the more ambitious ceilings in the gallery at Lanhydrock and the great chamber at Prideaux Place (see Country Life, June 9, 2010), both in Cornwall and both of about 1640.

A major difference is that both of those grander schemes incorporate biblical scenes, whereas the Rashleigh ceilings are entirely secular in their vocabulary. Whether this reflects Clotworthy’s attitude to life and religion, and whether the plasterwork as executed has any specific symbolism, must remain an open question.

The passing of the estate to a Cornish family in 1708 meant that Rashleigh quickly declined into the status of a tenanted farmhouse.

The building was spared extravagant renovation, but it also suffered attendant neglect: the hall became a workshop, the south wing degenerated into a garage with hayloft above and cows wandered through it. The parlour and great chamber ceilings survived, but the anteroom ceiling partially collapsed.

By the time the Tremayne family finally sold the estate in 1975, the building was in a parlous condition, from which successive new owners gradually rescued it, notably Lord and Lady O’Hagan in 1987–88. Some aspects of the restoration might now be judged rather heavyhanded, particularly the insertion of plate glass into windows where small leaded panes would have been more authentic and sympathetic, but the important thing is that Rashleigh Barton has survived and that Russell and Ali Mabon, its owners since 2006, have made it a comfortable, stylish and workable family home.

By Roger White; photographs by Justin Paget.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.