Queens' College, Cambridge: The seat of learning that helped set the mould for Cambridge's most beautiful colleges

John Goodall looks at the early history of Queens’ College, Cambridge, the college that helped define the tradition of academic architecture in the city. Photographs by Will Pryce for the Country Life Picture Library.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It has long been appreciated that the main courtyard of Queens’ College represents a new departure in the architecture of Cambridge. For the first time in the history of the university, this building, rapidly constructed between 1448–50, brought together in coherent architectural form all the chief elements — the gatehouse, hall, services, chapel and lodgings — of a college.

What is not generally understood, however, are the origins of this remarkable design, as suggested by the complex early history of the foundation.

During the late summer and autumn of 1446, a group of wealthy burgesses in the parish of St Botolph’s, Cambridge, made gifts of property towards the site of a new college in the city. They were undoubtedly encouraged in their generosity by their energetic parish priest, one Andrew Dokett. He had recently fought a legal battle to release St Botolph’s Church in the city from the controlling hand of Barnwell Priory and been confirmed as its rector.

He also had some connection with a student lodging in the city known as St Bernard’s Hostel (he has been described as its governor, but it’s not clear what the evidence for this is). As originally conceived, the new college was almost certainly intended as an aggrandisement of this institution.

The immediate spur to Dokett’s project was probably the wholesale transformation in the wider fortunes of Cambridge and its university brought about by the foundation here of King’s College by Henry VI in 1441. This began its existence as an isolated institution and grew by stages in ambition through the 1440s. Hitherto, Cambridge University had been a poor relation to Oxford with its great collegiate foundations of Merton, New College. With the example of royal patronage to encourage new donors, however, from the 1440s, Cambridge began rapidly to redress the balance.

Perhaps because of his interest in King’s College, Henry VI was pleased to support the process of establishing Dokett’s new site. As part of the legal formalities, Dokett was granted the parcels of land that made up the proposed site of the new buildings off Trumpington Street. Then, by a royal charter of foundation sealed on December 3, 1446, the King bestowed them on the corporate body of ‘St Bernard’s College’, comprising a president, Dokett, and four fellows, ‘or more or less’, depending on the resources available.

Within a few months of securing this licence, however, Dokett’s plans had changed. He acquired a new building plot for the college between the River Cam, the Carmelite Friary and what is today Silver Street, part of the present site of Queens’. In August 1447 he secured a new foundation charter that not only relocated St Bernard’s College to the new site, but authorised the institution to hold an endowment in perpetuity up to the value of £100 per annum (a very costly concession, the associated payment probably costing five times that sum).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Perhaps the most surprising thing about this charter, however, is its glittering witness list of noblemen and courtiers. What had begun as a local initiative was developing into something grander.

Explanation for this is undoubtedly to be found in Henry VI’s patronage of King’s College, Cambridge. In 1443, he formally linked this institution with another college he had founded, at Eton, next to his birthplace at Windsor Castle. His intention was that boys would pass from the school attached to the college at Eton to university at Cambridge (an idea first enshrined institutionally in the pioneering late-14th-century foundations of William of Wykeham, Bishop of Winchester). Work to both royal colleges was under way when they were connected, but Henry VI’s ambitions for them soon outstripped what had been accomplished. Incredibly, in early 1448, he determined to start them both afresh on a much grander scale.

Henry VI’s new architectural proposals were set out in an indenture known as ‘The King’s Will’, dated March 12, 1448. This directed that the new buildings at both Eton and King’s should be realised ‘in more notable manner than any [others] of my said realm’ and described plans to match. To help realise this stupendous vision, each institution was promised £20,000, to be paid in annual installments over two decades.

Henry VI was directly involved in preparing these proposals (and actually continued fiddling with them subsequently). Notes and even perhaps a drawing that informed the associated discussions still survive. The final designs presumably drew on a spectrum of professional advice, but they were probably framed by his principal mason, Robert Westerley, and — as the King knew and had visited Cambridge — were substantially discussed at Windsor and viewed through the prism of Eton, which, by degrees, became Henry VI’s particular obsession. All this is relevant to Queens’ College because it must explain an undated petition drawn up by Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, now held at Queens’.

The petition notes the recent establishment of Dokett’s college and observes that Cambridge University had ‘no college founded by any queen of England hithertoward’. Margaret, therefore, asked to be given the ‘foundation and determination’ of this institution, which would be ‘called and named the Queen’s College of St Margaret and St Bernard’ (Fig 8) so that, with King’s College, it would provide for the ‘conservation of our faith and augmentation of [a] pure clergy… like as [the] two noble and devout Countesses of Pembroke and of Clare founded two colleges in the same university called Pembroke Hall and Clare’. The activities of the college, the Queen proudly observed, would redound to the ‘laud and honour of [the] sex feminine’.

The King assented to the terms of his wife’s petition and issued yet another foundation charter, dated March 30, 1448. Events now moved incredibly fast. On April 8, the Queen issued a writ from Windsor Castle directing that the foundation stone be laid on her behalf by her chamberlain, Sir John Wenlock. He performed the task a week later, placing a stone at the south-east corner of the chapel. It bore a Latin inscription: ‘Our refuge will be in the power of our lady Queen Margaret; and this stone is in sign of this.’ To celebrate this event, the Queen issued her own foundation charter dated the same day, April 15, 1448.

The foundation stone must have been laid with a full knowledge of the design of the college, because the day before it was set in place — on April 14 — Dokett contracted for carpentry of the lodging ranges of the present main court. The contract is unusual, taking the form of a bond for £100 that had to be repaid if the work wasn’t completed by June 24 following. Even before that contract had expired, on March 6, 1449, another one was drawn up between the same parties and in the same form for £80 to roof the hall, furnish it with benches and fit the kitchen, buttery and pantry and the remains of the courtyard ‘in as hasty wise as they may goodly after the walls of the said houses be ready’.

Final payment for the second carpentry contract was due on September 14, 1450, by which time it seems reasonable to assume that the front courtyard had been completed. The layout imitates the arrangement of a grand house of the period, but is regularised to a striking degree. In time-honoured institutional fashion, the gatehouse incorporated the muniment chamber of the college (Fig 2). Its vaulted entrance passage directly faces the door to the screens’ passage across the courtyard (Fig 1). To the left of the passage are doors to the kitchen and services and to the right the hall, its interior lit with a richly detailed oriel window (Fig 6).

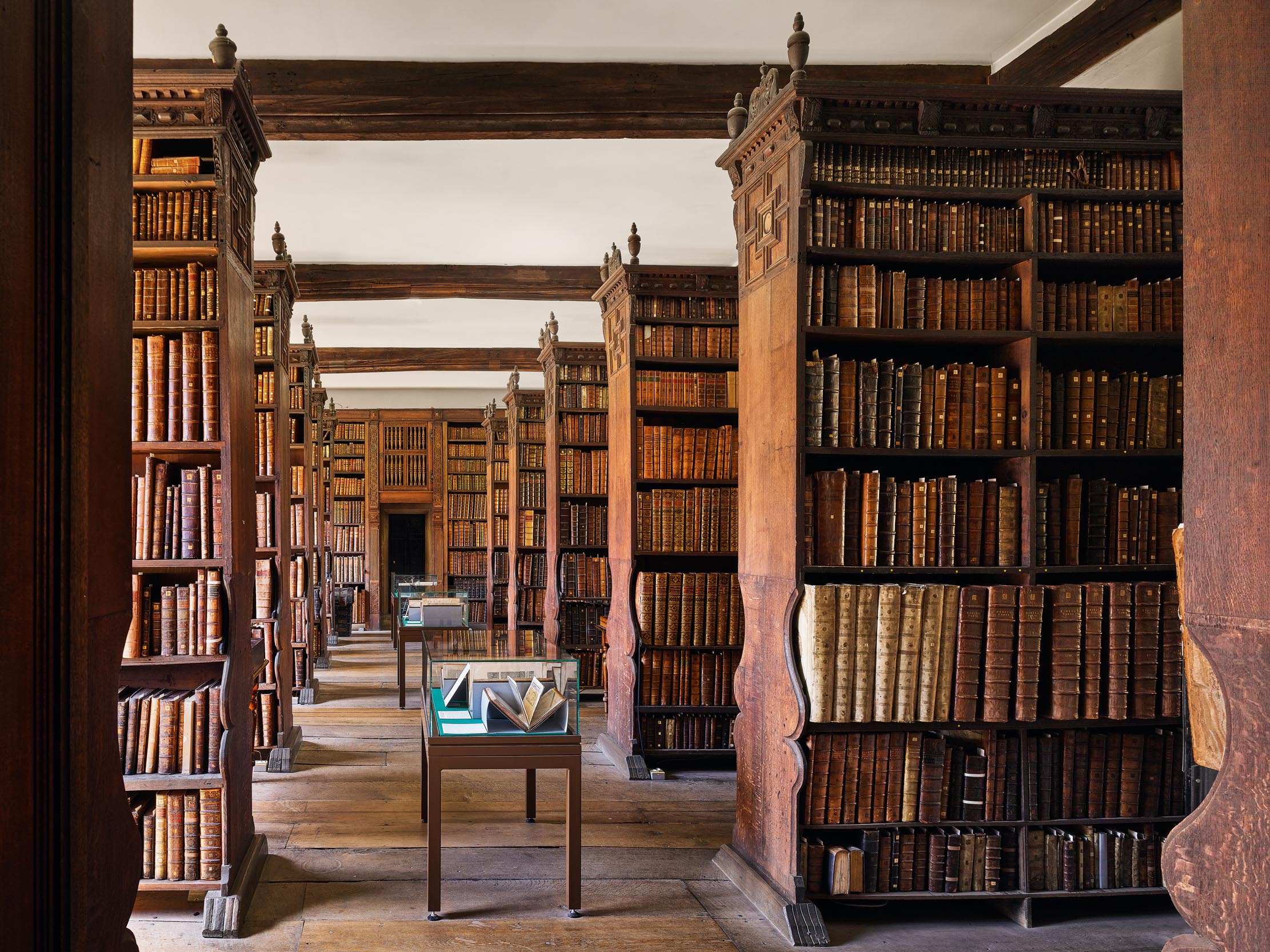

Opening off the dais is a parlour, the Combination Room (Fig 3). Subsumed within the volume of the north range are the library (Fig 7) and chapel (now also a library), the latter arrangement a striking point of contrast to the monumental chapels of Eton and King’s. The remainder of the court is encircled by accommodation. Beyond the main courtyard, towards the river, is a subsidiary court overlooked by the president’s lodgings (Fig 9).

The carpentry contracts of 1448 and 1449 have conventionally been cited as evidence that Dokett took sole responsibility for the construction of the college. Also, by extension, that the Queen had little further to do with her foundation. Yet building a college in two years flat implies access to resources far beyond those available to Dokett working alone. Added to which, the crucial stages in the process of design evidently took place in a short window of time — March and early April 1448 — which precisely coincides with the redesign of King’s College and Eton by Henry VI. The idea that the Queen didn’t take a direct interest in the architecture of her own college at this particular moment, therefore (and after having just founded it), is almost incredible.

The Queen’s involvement has a bearing on the central question of who designed the college. It’s usually attributed to the master mason Reginald Ely, who, by 1444, was in charge of the works at King’s College and, from at least 1446, was a parishioner of Dokett’s in St Botolph’s. Certainly, it’s quite clear that the two men knew each other well and it seems plausible that Ely contributed in some way to the new college; indeed, his will of 1463 grants property to the foundation. The attribution to Ely places Queens’ in a tradition of Cambridge building and explains its regularised plan as an evolution of ideas already present in the city and university.

Assuming the involvement of the Queen, however, the context of the design looks radically different. The debates that framed The King’s Will largely took place at Windsor and, although Ely presumably contributed to these, the senior professional who must have directed them and been physically present was the King’s master mason, Robert Westerley. Would it not have been with him, therefore, that the Queen devised and signed off the plans for her college? If so, the Cambridge precedents for Queens’ are an irrelevance and its design should instead be understood as a wholesale importation to the university.

That interpretation — and Westerley’s involvement — might explain several surprising features of Queens’. For example, the walls (built of clunch) are faced in high-quality brick that is detailed in stone and ornamented with patterns of brick burnt black in the kiln, termed diaper (Fig 5). This combination of materials is most obviously prefigured at Eton in the 1440s (and in Westerley’s lost work at Syon, Middlesex) rather than in any Cambridge building. Indeed, the use of brick in the 1440s is itself a mark of court-connected architecture. Similarly, the main façade incorporates miniature turrets (Fig 4), an architectural borrowing from Eton that is probably derived — as is the gatehouse of Queens’ — from the 14th-century remodelling of the Upper Ward at Windsor Castle.

Whatever the provenance of its design, the remarkable speed at which the college was completed would itself prove important. In 1450 — when construction was drawing to an end — a sequence of political crises culminated in the popular uprising known as Jack Cade’s Rebellion. Three years later, after a period of steadily mounting political tension, the King had a mental collapse and the kingdom slid into the internecine struggle familiarly known as the Wars of the Roses. Work to Henry VI’s colleges lapsed, leaving their chapels as vast, roofless and incomplete shells.

The same political difficulties probably account for Margaret of Anjou’s seeming lack of interest in her college in the 1450s and Dokett, ironically, lived to secure the support of her Yorkist rival, Elizabeth Woodville, as the titular founder of the college; hence the plural form of its name.

Despite Lancastrian misfortunes, however, Queens’ did stand physically complete and it offered a much more realistic model for future imitation in Cambridge than King’s. In the process, it shaped the whole tradition of architecture in the university. We will look further at the subsequent development of its buildings in the next article.

Newnham College, Cambridge: 'The most convincing and delightful example of the "Queen Anne" style in existence'

To mark the 150th anniversary of the foundation of Newnham College and the arrival of women scholars in Cambridge, Kathryn

Credit: Justin Paget for the Country Life Picture Library

Magisterial and picturesque: The Master’s Lodge at St John's College, Cambridge

Between 1863 and 1865, Sir George Gilbert Scott created a new lodge for the Master of St John’s College, Cambridge.

Credit: Will Pryce/©Country Life Picture Library

The Chapel of Trinity College, Oxford: A return to splendour

One of Oxford’s most admired interiors has been revived, as John Goodall reports.

The snowdrops of Oxford: How the city fell in love with winter's most entrancing flowers

The city of Oxford has long been a destination for snowdrop enthusiasts and one of the university’s colleges displays its

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.