Samuel Lysons: The man who revealed the Roman Cotswolds

The antiquarian Samuel Lysons played an important role in recording the Roman villas of the Cotswolds. Clive Aslet looks at his remarkable career and methods.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For an archaeologist such as Samuel Lysons (1763–1819), the Cotswolds was a good place to be born. By the 4th century AD, the area had acquired the highest concentration of villas for the Romano-British elite in the country.

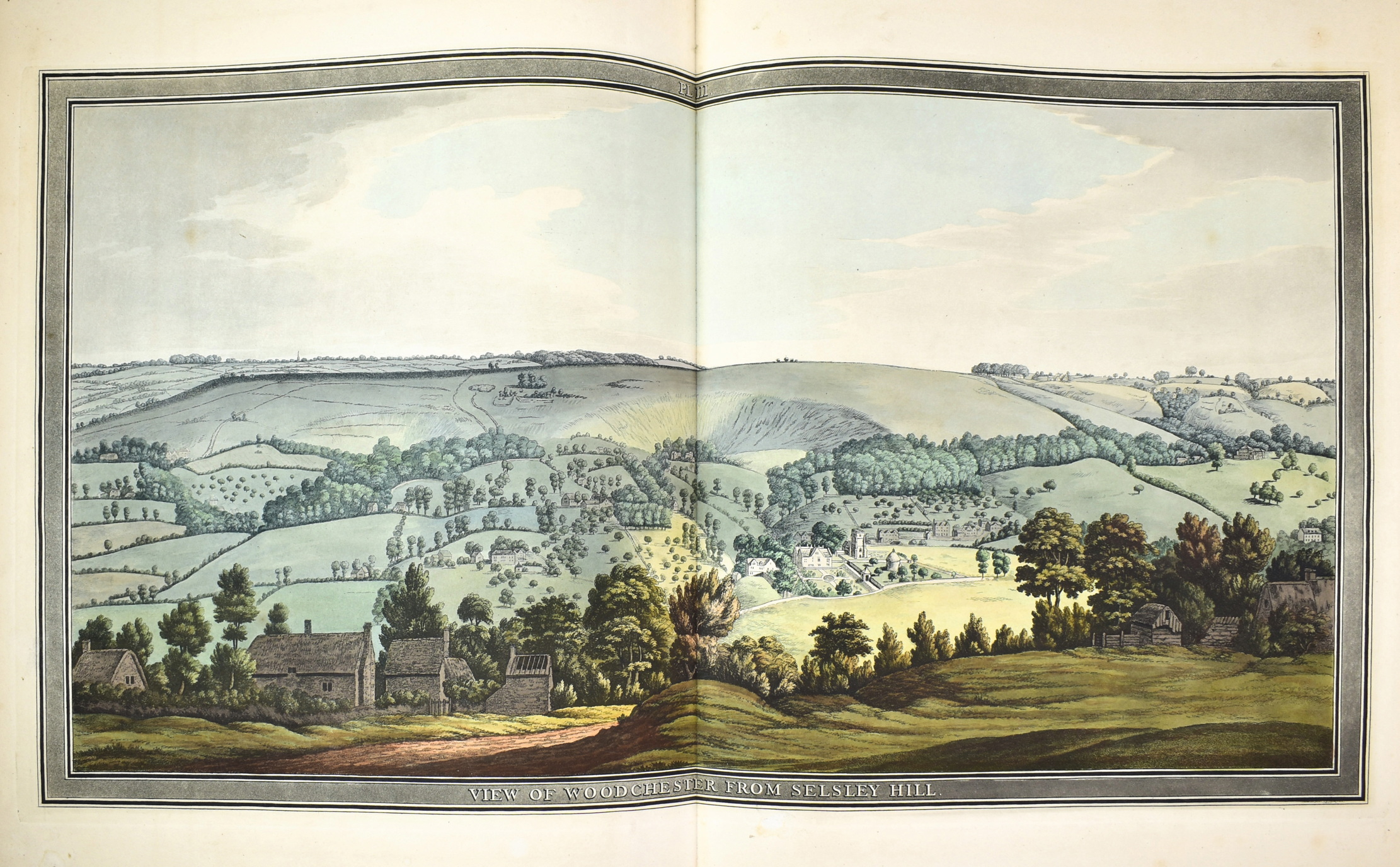

Woodchester was the largest of them, having 64 rooms and three courts, and Lysons’s excavation of it in 1793 established his reputation. It was one of many digs from which finds were sumptuously published after his drawings or with etchings made by himself. The best of the artefacts were among those he gave to the British Museum, founding its Romano-British collection.

The term archaeologist is, of course, an anachronism; a younger friend of Horace Walpole, Lysons was proud to call himself an antiquarian. Archaeology — a word that had only recently come into currency — then meant the study and display of ancient objects, not the broad study of places or culture by forensically analysing what remains.

Today’s more rigorous archaeologists can be dismissive of his work, with its emphasis on making spectacular finds rather than diligently exploring the layers of a site to establish its historical development. Nor, to modern sensibilities, did Lysons improve the objects he unearthed by restoring them to their imagined condition when they were first made. This, however, was common practice both in the sale of antiquities and their representation in books at the time. Where he differed more positively from many of his contemporaries was in recording smaller finds.

Overall, however, we ought to be grateful for Lysons’s endeavours simply because much would have disappeared but for his interest. The perils to which newly discovered sites were exposed in the late 18th century is plain from a letter in the Gloucester County Archives written to him by a Mr Luders in 1807. Announcing that the remains of a villa had been found outside Bath, the writer urged him to hurry there ‘before the frost & the various visitors should lessen their size & beauty’.

In 1810, Lysons described his method to Henry Brooke, one of whose tenants had found ‘a quantity’ of tessellated Roman pavement a couple of feet beneath a ploughed field near Cheltenham. ‘The first thing,’ Lysons replied, in a letter quoted by Lindsay Fleming in a short memoir published in 1934, ‘would be to get half a dozen mason’s labourers or ditchers who are used to the management of the spade, they would make considerable progress in a few hours as the pavement does not lie deep.’ He then recommends cutting trenches at right angles until a wall was found, which could be followed. It may sound rough and ready, but was as methodical as any other way of proceeding at the time.

Confusingly, there were three generations of Lysons called Samuel. The eldest, the father of the figure who concerns us, was the rector of Rodmarton, near Cirencester, with antiquarian tastes. The third Samuel Lysons was a nephew who was also rector of Rodmarton and published The Romans in Gloucestershire, 1860, among other books.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Our Samuel Lysons was educated at home before being sent to the grammar school at Bath, then at the height of its prosperity. There he trained with a lawyer, before being called to the Bar. It was said that he might have become Lord Chancellor, but Bath opened other avenues to him. He met Mrs Piozzi, who introduced him to Dr Johnson (who judged him to be ‘an agreeable young man’). Another friend was the portraitist Thomas Lawrence, with whom he discussed his passion for etching and engraving, which kept him up long into the night.

Lawrence painted his portrait, too. A young Lysons is shown gazing clear-sightedly into the distance, delicate features full of intelligence; he expressed his opinions, with a zeal some people found disconcerting, in a fearless voice. ‘Want of manner,’ as Lawrence put it, was generally forgiven due to his sincerity and attainments. From 1785, he exhibited at the Royal Academy, as well as practising law at Middle Temple, and, in 1786, was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries.

In the first week of his coming to London, he met no less a person than Sir Joseph Banks, the gentleman botanist who had travelled with Capt Cook on the first of his great voyages of exploration and was now advising George III on the development of Kew Gardens. As president of the Royal Society, a post he occupied for 41 years, Banks promoted contact between the scientists of that institution and the topographical historians of the Society of Antiquaries, regarding the accurate documentation of the historical record as part of British Science. Lysons himself rose to be treasurer and later vice-president of the Royal Society.

In 1796, Banks took him to show his drawings of Woodchester to the Royal Family, who made him a favourite; he became — in the King’s words — ‘teapot man’ to Princess Elizabeth, by sending her interesting teapots he found during his travels to add to her porcelain collection. He also dispatched finds from his archaeological work. In 1803, royal influence secured Lysons a post for which he was ideally suited: Keeper of Records at the Tower of London. He diligently applied himself to the organisation of the archive and never practised law again.

Archaeology was but one branch of Lysons’s broader concern for local history. This found expression is an almost insanely ambitious project that he undertook with his beloved brother Daniel, Magna Britannia, being a concise topographical account of the several counties of Great Britain, the first volume of which appeared in 1806. The subtitle belies the scope of the venture. There is nothing obviously ‘concise’ about it.

The Lysonses sought to assemble all the available knowledge about the counties of Britain, contemporary, as well as historical. They listed squires and gamekeepers, as well as churches and ancient monuments. Proceeding alphabetically, they started with Bedfordshire, but had not got beyond Devon when Samuel died. The Gloucestershire chapter was never published. In a letter of 1793 he describes himself as having ridden about the county ‘(not less than Eight hundred miles) since I arrived in it, making drawings and when bad weather drove me home, etching them…’. But that was for a different project: Views and Antiquities in the County of Gloucester hitherto imperfectly or never engraved, which appeared in 15 parts between 1791–1803.

A sketch of the church at Woodchester shows workmen on ladders scaling the roof: repairs were under way. But this was reworked to depict some more interesting work in the foreground, being undertaken by a couple of labourers. One, in a smock, is wielding a pickaxe, as his companion looks on, leaning on a long-handled spade. They are uncovering the remains of the Woodchester villa under Lysons’s own eye: he shows himself seated, with sketchbook, on the edge of the trench.

Banks may have given financial help, as, on one occasion, Lysons thanked him for providing a tent, adding that he intended to have closed my campaign ‘till the Easter vacation, but further discoveries have been made which interest me so much that I shall not fear bad weather, I shall pitch it over a mosaic pavement & sit like a Roman general, commanding my troops, in their works I think we should apply for some of the overplus flannels…’.

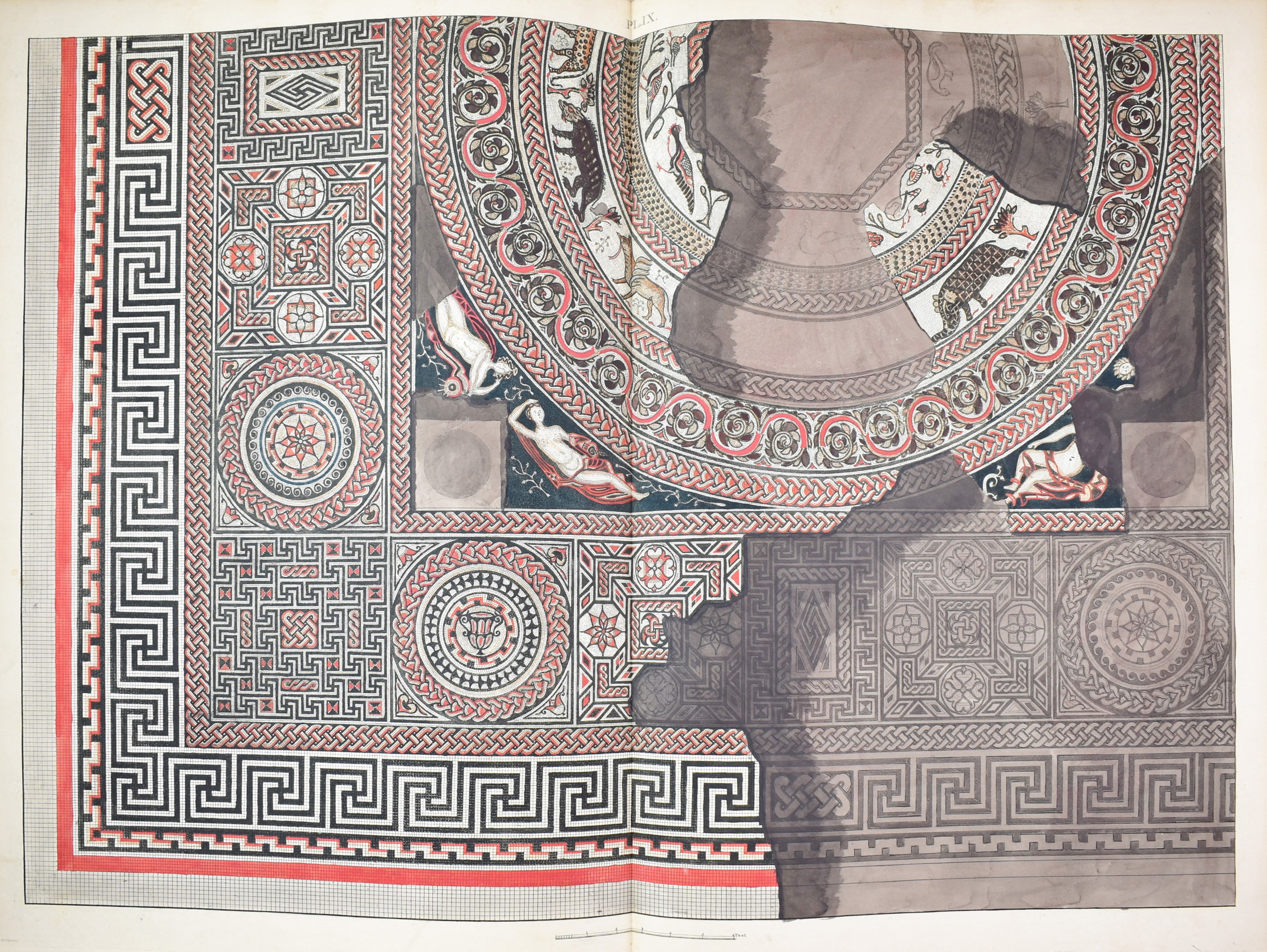

In 1797, his findings were published in An Account of the Roman Antiquities Discovered at Woodchester, with a text in English and French and dedicated to George III. The French translation may have been intended to appeal to Napoleon, as Lysons sent him a copy, in the hope that ‘the savants of France might embark on similar researches’. Knife blades, fragments of sculpture and a scrap of mosaic pavement were given to the British Museum, although the ‘great pavement’ depicting Orpheus with his lyre charming animals — ‘the largest and finest known in Britain,’ according to the Pevsner’s ‘Buildings of England’ — was left in situ; last uncovered in 1973, it is best appreciated in Lysons’s superb coloured engraving.

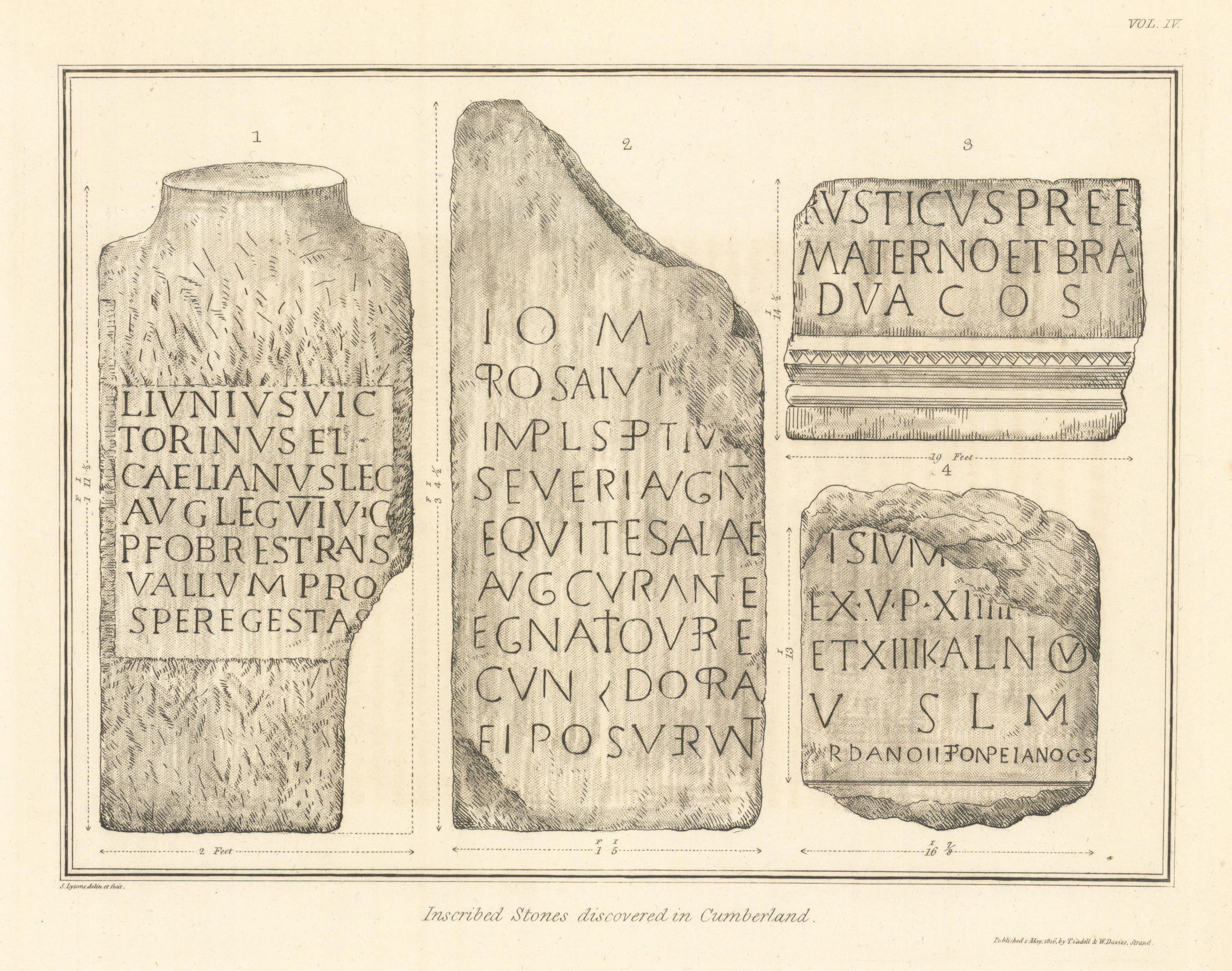

In 1801, Lysons published the first volume of arguably his greatest work: Reliquiae Britannico-Romanae: Containing Figures of Roman Antiquities Discovered in Various Parts of England. As he got older, he was not only increasingly fêted, but suffered from rheumatism (he was glad when a legacy from an aunt enabled him to keep a carriage). This may explain why the labour of producing the book was shared with Richard Smirke, brother of his old friend Sir Robert Smirke, architect of the British Museum — Richard being ‘an artist distinguished for the accuracy of his pencil, and his zeal for antiquarian exactness’.

The third volume features one of Lysons’s most glamorous Cotswolds discoveries, the villa at Withington. The frontispiece to that volume shows the work under way. We see trenches and mosaics, wooden fences and tents, all somewhat rudimentary, but orderly; in the middle distance, men are at work digging in a field striated with ridges and furrows (probably an indication that the pasture had been ploughed up during the Napoleonic Wars, rather than a survival of medieval cultivation). The best of the Withington mosaics were sent to the British Museum, where some have been on display ever since. As he wrote in the Advertisement to Reliquae, the engravings copied them ‘with scrupulous fidelity, [being] carefully coloured from the originals’.

For Lysons, accuracy was paramount, although, as he charmingly admitted in a letter of 1809, difficult to achieve. He had ‘long given up being astonished, or surprised at any inaccurancy in my own Drawings or any body else’s. — I am only astonished when upon a comparison with the things themselves I find them accurate. N.B. Since I have taken this method my astonishment has been very little excited indeed’. Very few copies of the Reliquae were published, perhaps less than 100, and many plates were cancelled due to Lysons’s perfectionist standards.

A print by George Cruikshank of 1812 shows Lysons in his element at the ‘Antiquarian Society’, of which he was then vice-president. Wearing a brown coat, his hand on a volume of the Magna Britannia, he is listening intently, with a look of vigorous intelligence, to the secretary, Nicholas Carlisle. Seven years later, his pre-eminence was recognised by the Royal Academy, when he was made its Antiquary. It was a final honour. He died the same year, unmarried, of heart failure. On hearing the news, Lawrence wrote to Joseph Farington from Rome, ‘there was no man high in station or eminent in genius, but would have mentioned Mr Lysons as his guest with security of a favourable impression on the hearer’s mind’.

Clive Aslet is a journalist and architectural historian. He edited Country Life for 13 years

Credit: Bettmann Archive via Getty

'We had to extract her by her legs in an undignified fashion so she could meet him and join us all at the table': The trials and tribulations of the country-house lift

Anyone with a fear of being trapped in a lift may wish to look away, warns Melanie Cable-Alexander, as she