Sir Christopher Wren: The life and times of a legendary architect, from 'miracle of a youth' to national treasure

Personable, yet naturally reserved, ‘that miracle of a youth, Mr Christopher Wren’ not only designed many of our most notable monuments, but also an artificial eye. Three centuries on from his death, Clive Aslet considers the man behind the architecture.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

One of the finest portrait busts carved in England during the late 17th century can be seen in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Made in 1673, it shows Christopher Wren at the age of 40, with rich curly locks tumbling to his shoulders and a loose shirt beneath the classical robe in which he’s swathed. The features are alert, mobile, determined; high eyebrows suggest scepticism, with Wren’s somewhat bulging eyes seemingly trained on a distant object that only he can see.

Edward Pierce, the stone carver and mason who made this tour de force, perhaps after a lost French original, worked with Wren on several projects and must have been in his company many times. He knew his subject well and brilliantly captures the quality for which Wren has always been known: genius.

Every contemporary description of Wren confirms the evidence of the bust. Although diminutive in stature, he was a handsome man, whose dazzling gifts were recognised from childhood. As an adolescent at Oxford, he would be called ‘that miracle of a youth Mr Christopher Wren’. Unlike some other prominent figures in the Royal Society — the uncouth Isaac Newton, the distinctly peculiar Robert Hooke — he was invariably courteous and frequently to be seen in Hooke’s company in the coffee houses around Whitehall, where he lived and worked.

In architecture, his immense oeuvre, from St Paul’s Cathedral and the City churches to Hampton Court, Kensington Palace and the Trinity College library in Cambridge, seems to reflect the balance and reasonableness of his personality. As a mathematician and astronomer, he sought to achieve the ‘natural beauty’ (as he called it in one of the tracts gathered in Parentalia by his son, also Christopher), which belonged to geometry and ideal proportions. ‘Customary beauty’ might be attached to things we have grown up with, ‘as familiarity breeds a love to things not in themselves lovely’, but was a snare and a delusion (although he was capable of designing in Gothic for associational reasons: see the great Tom Tower at Christ Church, Oxford).

Christopher Wren: Timeline of a life

- 1632 Born in East Knoyle, Wiltshire

- 1651 Graduates from Wadham College, Oxford

- 1653 Obtains an MA and is elected fellow of All Souls College, Oxford

- 1657 Appointed professor of astronomy at Gresham College, London

- 1661 Elected Savilian professor of astronomy at Oxford

- 1662 Co-founds the Royal Society

- 1662–63 Designs the chapel at Pembroke College, Cambridge, and the Sheldonian Theatre at Oxford

- 1665 Visits Paris and meets Gian Lorenzo Bernini; the trip greatly influences his work

- 1669 Appointed Surveyor-General of the King’s Works. Marries Faith Coghill

- 1670 Oversees the reconstruction of the churches lost in the Great Fire of London of 1666

- 1671 Designs the monument to the Great Fire of London with Robert Hooke

- 1673 Knighted by Charles II

- 1675 Wren’s wife dies. His revised plans for St Paul’s are accepted after several rejections. Commissioned to design the Royal Observatory at Greenwich

- 1677 Weds Jane Fitzwilliam, who dies three years later

- 1680 Becomes president of the Royal Society

- 1682 Commissioned to design the Royal Hospital, Chelsea

- 1689 Begins remodelling work at Kensington Palace and Hampton Court

- 1695 Starts construction of the Royal Naval Hospital at Greenwich

- 1696 Begins building the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral

- 1697 The first service is held at St Paul’s

- 1698 Appointed Surveyor General for Repairs to Westminster Abbey

- 1711 St Paul’s is finally declared complete

- February 25, 1723 Dies

Wren could make a grand Baroque gesture when he needed to, as in his Roman Catholic chapel for James II and the Royal Naval Hospital, but it was far from habitual with him. Brought up as a High Anglican, he distrusted overt emotionalism — or enthusiasm, as it was coming to be called. Albeit outwardly personable and well mannered, he was impenetrably reserved. A Hooke or a Pepys recorded even their sexual practices in their diaries. By contrast, we know next to nothing about Wren’s two wives or his feelings towards them.

It is easy to imagine why this might have been. Born in 1632, Wren was the only boy in a large family of girls. Like his great Edwardian votary Sir Edwin Lutyens, he was a sickly child and, although he passed through Westminster School, his stint there was short. Instead, he received his first lessons from his father, also Christopher, at his Wiltshire rectory. Dr Wren was remembered in Parentalia as ‘a Learned Man, skillful in all the Branches of Mathematicks’, who, according to the architect Christopher’s own account, introduced him to Organics (biology) and Mechanics (engineering); he rose to become Dean of Windsor. Yet even that height was exceeded by Wren’s uncle Matthew, who became the Puritan-hating Bishop of Ely.

The cosiness of this boyhood ended abruptly with the Civil War from 1642. Bishop Wren was imprisoned, not to take his liberty until 1660; his brother the Dean was reduced to burying the most precious insignia of the Order of the Garter in the garden before the Windsor deanery was sacked by Parliamentarian troops. There was no likelihood of Wren following his father and uncle into the Church.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Smitten by a bad illness in 1647, Wren convalesced at the home of a famous doctor, Charles Scarburgh, whose interests included mathematics, anatomy, optics, astronomy and architecture — all later pursued by Wren. From there, he went to Wadham College, Oxford, where the new Warden, Dr John Wilkins, was not only tolerant of Royalists but a Virtuoso, as men of science were then called; he also speculated about the possibility of flying machines, space travel and submarines. As a gentleman commoner who could dine at high table, Wren joined a group of inquisitive and empirically minded individuals that later founded the Royal Society.

According to Parentalia, Wren’s contributions to the New Philosophy, exhibited at Wadham, included an Artificial Eye, an instrument for taking a copy when writing a document, ‘Several new Ways of graving and etching… Divers new Engines for raising of Water, A Pavement harder, fairer and cheaper than Marble… A way of Imbroidery for Beds, Hangings, cheap and fair. New Ways of Printing. Pneumatick Engines’. The list goes on.

Not all the credit can go to Wren alone for these inventions, because he worked collaboratively. (This would also be the case with his architectural career, raising many questions of attribution.) But we can see that Wren bent his mind to the solving of practical problems. Soon, he would occupy the chair of astronomy at Gresham College in London, followed, in 1661, by the Savilian Chair of Astronomy at Oxford; but astronomy also had its practical application, as a means of helping navigation, which Wren was required to teach at Gresham. His interest in optics stretched to both telescopes and microscopes, as well as the dissection of the eyeball of a horse. Scarcely had he returned to Oxford before he was unofficially studying the condition of old St Paul’s Cathedral, abused, then neglected, under the Commonwealth.

Wren’s first foray into architecture came in 1663, when his uncle Matthew — the no-longer-incarcerated Bishop — gave a chapel to Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he was Master. This modest structure was followed by the more ambitious Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, somewhere in which the public ceremonies of the university could take place. These buildings introduced ideas that remained constant throughout Wren’s career. Both were Classical in style, reflecting his reading of his father’s copy of Vitruvius’s treatise and his admiration for the architecture of Ancient Rome, although he only knew it from engravings; both provided unencumbered spaces that allowed congregation or audience to see and hear everything before them. The design is based on a D-shaped Roman theatre — Wren wanted to keep the auditorium free from obstructive columns; to do this he made use of a system recently invented by the Savilian professor of Geometry, John Wallis, for creating self-supporting flat roofs over spaces too big to be spanned by beams. Beneath it, the ceiling was painted in trompe-l’oeil to represent the awnings pulled over Roman theatres to keep off the sun.

Two years earlier, Wren had given the King drawings of insects made with the help of a microscope, followed by a lunar globe depicting the surface of the moon, which could be studied through the new telescopes. This may have inspired Charles II to ask Wren to direct the fortification of Tangier, an arduous job, which he turned down on grounds of health. Disappointed on this occasion, the King would soon prove a great patron. During his exile, he had seen at first hand the role that architecture played in Louis XIV’s projection of monarchy.

Wren himself went to France in 1665, when the University of Oxford was closed by plague. Paris not only provided access to the scientific community, but gave Wren, as he wrote on his return, ‘daily conference with the best Artists’, among them Francois Mansart and a grumpy Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose bust of Louis XIV may have inspired Wren to commission the one from Pierce. He adopted the French manner of drawing. He studied the construction of domes, a feature of building completely unknown in England. It was the only time he would venture overseas and the trip formed him. By chance, it also enabled him to escape the Great Plague.

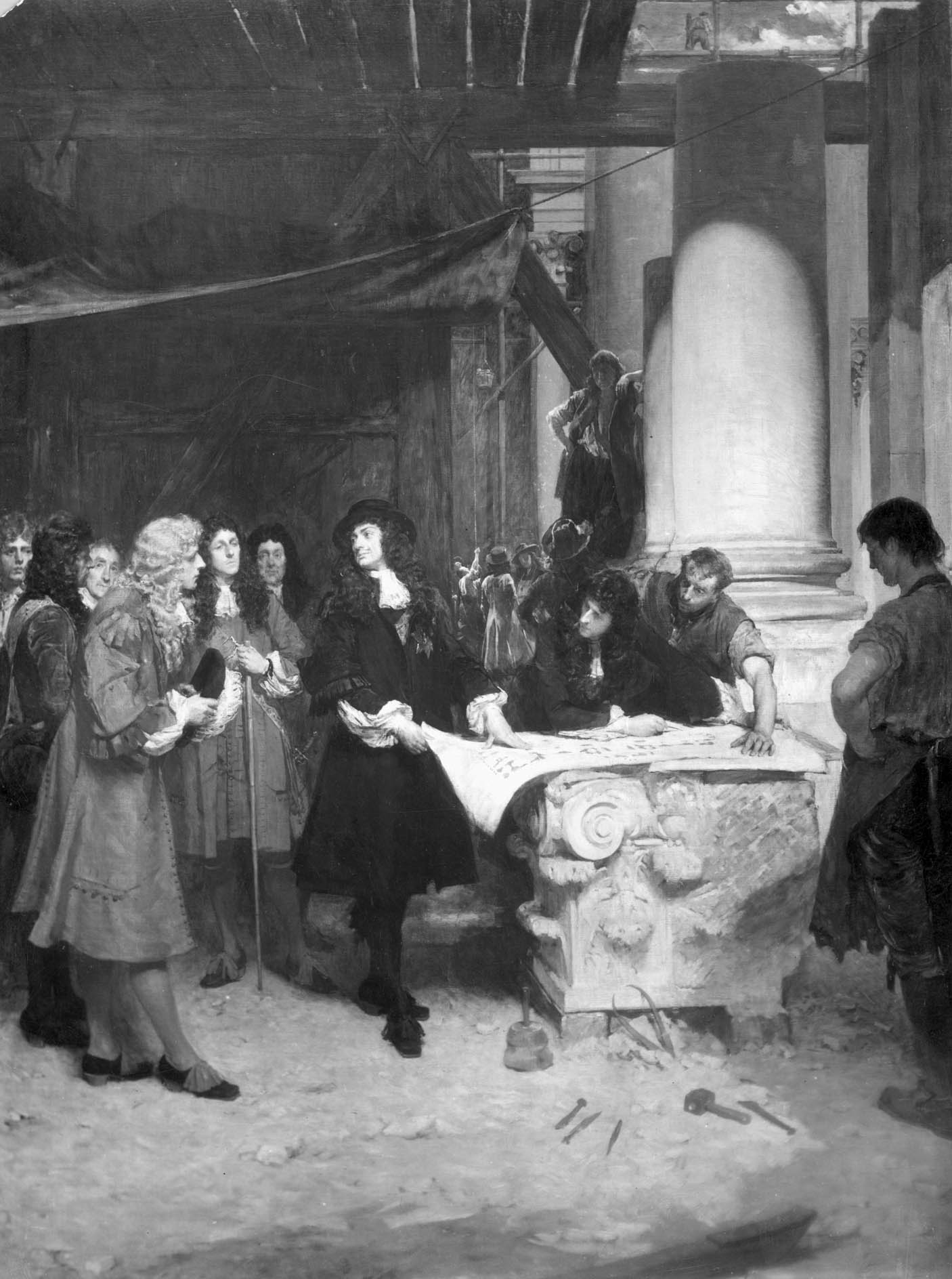

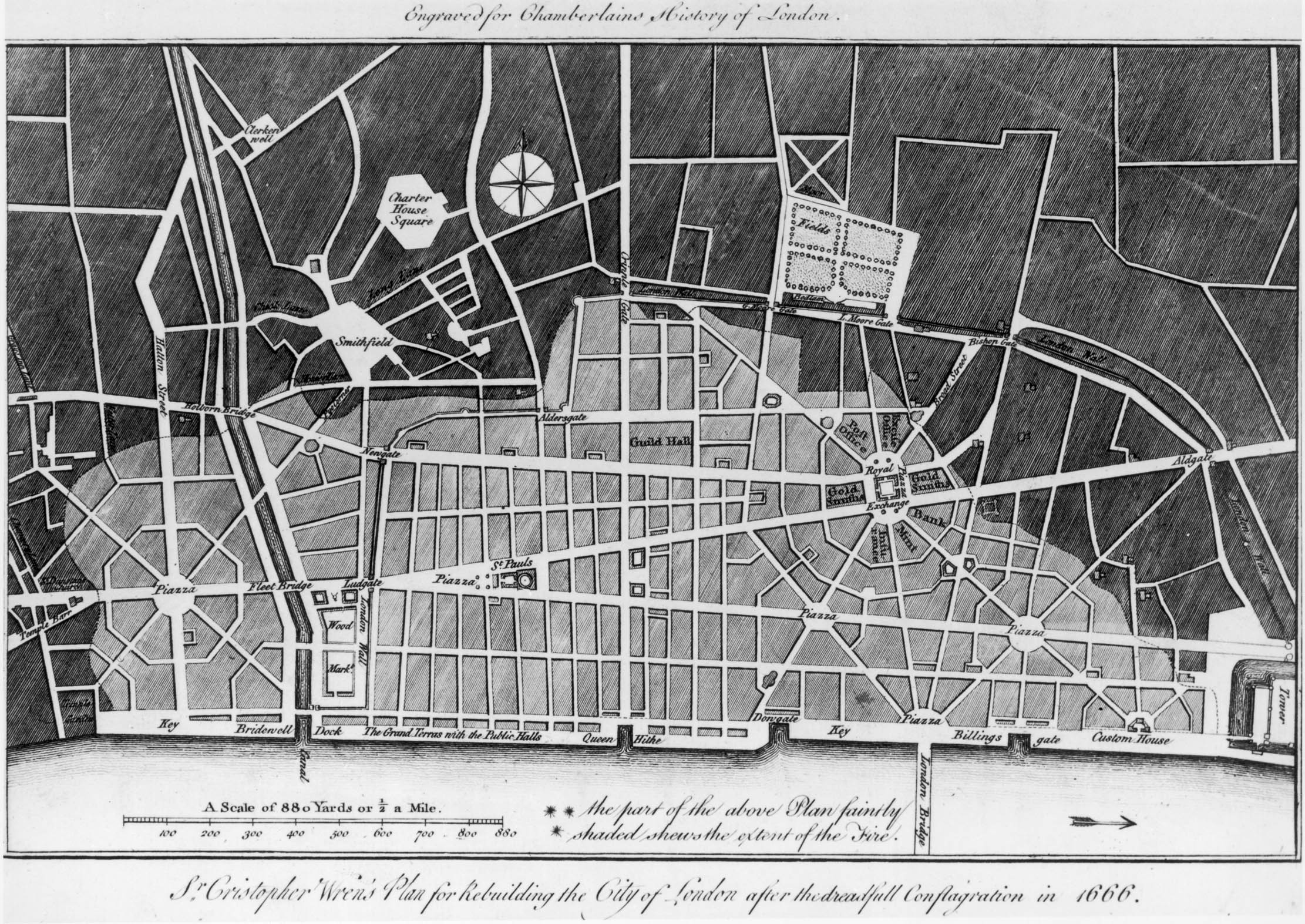

Wren returned in March 1666, a few months before the Great Fire turned the City of London into a blank canvas for architecture. He rose to the challenge by presenting the King with a scheme to rebuild London along new lines, replacing narrow, irregular medieval streets with order and geometry: grids, avenues and piazzas. It would have made London the most beautiful city in Europe.

In the end, the need to get London working again, before merchants moved their businesses elsewhere, meant there was no time to negotiate with the numerous private owners whose properties were now ruined; the City was rebuilt to the old plan. But it was impossible to patch up the old St Paul’s, which had already been in a bad way; Wren was chosen to design the first new English cathedral for centuries and the only one then to be completed in the lifetime of its architect. He also designed the majority of the ‘Wren’ City churches — 53 of them — and had oversight of those primarily designed by his colleagues (it was not only for Wren that architecture was collaborative in the 17th century).

The theme unifying this great corpus of building was a personal adaptation of the Baroque to an Anglican agenda, based on clear sight lines and rich decorative carving by Grinling Gibbons and others — not in the form of gesturing saints, but swags and garlands of fruit. On their complex medieval sites, each church presented a problem, which Wren solved through geometry. Aisles were avoided where possible. Domes created magnificent central spaces, although in tension with the altar at the east end. One masterpiece among many is St Stephen’s Walbrook, which combines a rectangle and square with an octagon and circle, all lit by clear glass windows — as Wren said, ‘nothing can add beauty to light’.

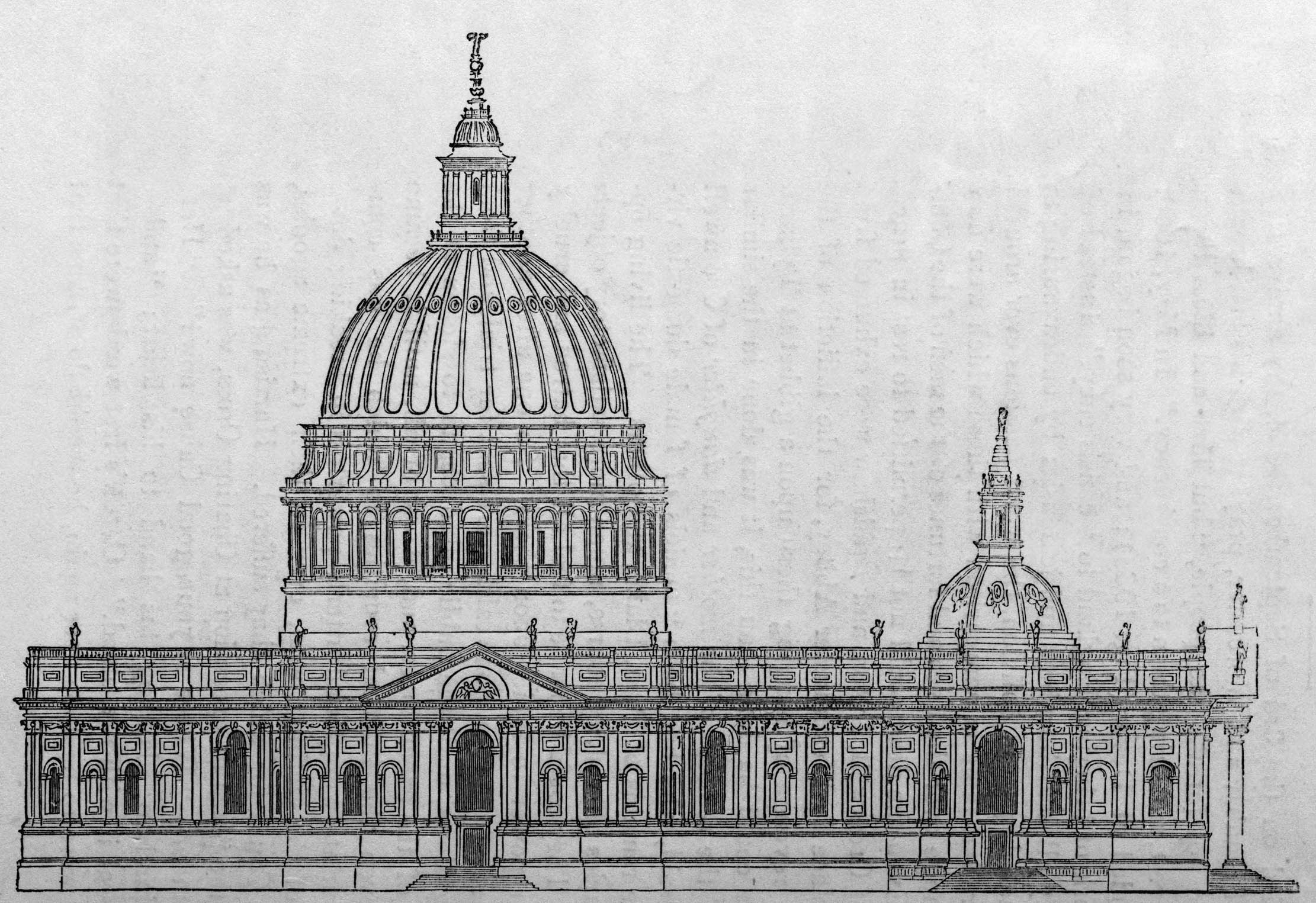

Work on St Paul’s did not get under way for full 20 years after the Great Fire. It took until 1696 for the construction of the dome to begin. By this time, the design had gone through several stages, from being a Greek cross to the form revealed in the Great Model of 1672–73, still displayed in the St Paul’s Trophy Room, in which a Greek cross would have been approached through a portico of giant Corinthian columns and a vestibule surmounted by a secondary dome.

Although it was approved by the King, the Great Model design may have proved too radical for the cathedral authorities, whose services did not always attract large congregations, nor could it have been built in stages, as had been specified.

There were other iterations and the cathedral as built emerged only in the sixth design. This has a more pronounced nave, to suit Anglican liturgy, and stronger piers to support the dome. The dome has been a symbol of London ever since it was raised. It represents an extraordinary feat of engineering, due to the need to support a tall stone lantern. To achieve this, the outer dome, built of timber covered in lead, hides the load-bearing structure: a brick cone, itself only 1ft 6in thick, reinforced by an iron chain.

This relatively light structure relieved the pressure on the piers of the crypt, which were showing signs of trouble. The profile of the cone was calculated using previous work by Hooke on the ‘hanging chain’ or catenary arch, which again lessened the weight. Wren rightly called the finished cathedral ‘my great work’, based on principles derived from the ancient world.

In the 1680s, Wren built the Royal Hospital at Chelsea, to house soldiers ‘broken by age or war’ for Charles II, but the King never obtained the palace he had been craving since his first days on the throne: the King’s House at Winchester was incomplete at his death.

It says much for Wren’s reputation that he succeeded in retaining the Surveyorship of the King’s Works, first awarded in 1669, through the reigns of James II, William and Mary and Anne. William and Mary were luckier in their palace projects than Charles II, as Wren created Kensington Palace out of an old Jacobean pile and fitted the rambling mass Hampton Court for their occupation; economy, speed of building and the shortage of Portland stone caused by the quantity being used for St Paul’s dictated that, like Chelsea Hospital, they would be built from brick.

After Mary’s sudden death from smallpox in 1694, William perpetuated her memory by building the Seamen’s Hospital at Greenwich — a far more palace-like structure than his own Kensington. Out of piety to the earlier Stuarts, the Queen’s House, begun by Inigo Jones for James I’s Anne of Denmark and finished for Charles I’s queen, Henrietta Maria, was retained, forming a diminutive centrepiece Wren had hoped to replace with a chapel crowned by a dome almost on the scale of St Paul’s. As a result, the focal point of the grandest parade of Baroque architecture in Britain is a small, chastely rectangular house, designed as a caprice.

In 1711, Wren had his portrait painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller: his hand holds a pair of dividers and rests on a plan of the newly completed St Paul’s, weighted down by a copy of Euclid. An immense full-bottomed wig has replaced the abundant curls of Pierce’s bust and the face has lost the old brio; it is pensive, haughty, sad.

He was then 79 and would live for another 12 years. Old age brought disappointments and it had always pained him that Christopher, his son, was not clever. He would, however, surely have been pleased with the epigraph Christopher came up with for Wren’s tomb in St Paul’s: Lector, si monumentum requires, circumspice. Reader, if you seek his monument, look around.

Tributes to Christopher Wren

Events are being held throughout 2023 to mark the 300th anniversary of the death of Christopher Wren. Here are a few of the biggest, but you can see wren300.org to find out more.

- March 8–September 30 @Greenwich: 300 years of Wren guided tour, Greenwich, London SE10

- April 15 The Georgian Group 2023 Symposium on Wren’s later work and

- April 16 Wren 300 concert, both Trinity College, Oxford

- May 17 Christopher Wren’s Medical Discoveries: ‘Architect of Human Anatomy’ lecture, Gresham College, London EC1

- June 13–24 Wrenathon choir performances, various churches across the City of London

- June 14 Sir Christopher Wren: Architect & Courtier lecture, Gresham College, London EC1

- September 22 The Professional World of Sir Christopher Wren conference, Ax:son Johnson Centre for the Study of Classical Architecture, Cambridge

St Paul's Cathedral: Part church, part street spectacle, all masterpiece

St Paul's may not have the London skyline to itself as it once did, yet Sir Christopher Wren's masterpiece still

Carla Carlisle: 'I felt a surge of gratitude and hopefulness that’s hard to describe. You could call it Thanksgiving.'

A visit to St Paul's Cathedral provokes a flood of feelings in Carla Carlisle.