The Great Hall at Hampton Court, the building that 'brings the visitor closer to the world of Henry VIII than any other'

John Goodall looks at the remarkable history of Henry VIII's celebrated great hall at Hampton Court Palace.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For all the changes it has undergone, Hampton Court arguably brings the modern visitor closer to the world of Henry VIII than any other building in Britain. Its link to the founding king of Protestant England has always been important, not only to the popular perception of the palace, but also to the monarchs who occupied and developed it into the 18th century. Towards the end of its period of royal occupation, indeed, there were several proposals to rebuild the court.

All these grandiose schemes, however, aimed to preserve at least one inherited structure: Henry VIII’s great hall. The choice was not fortuitous. Not only was the hall exceptionally large and splendid, but it was the public centrepiece of the Tudor palace and, by extension therefore, its chief and most imposing architectural antiquity.

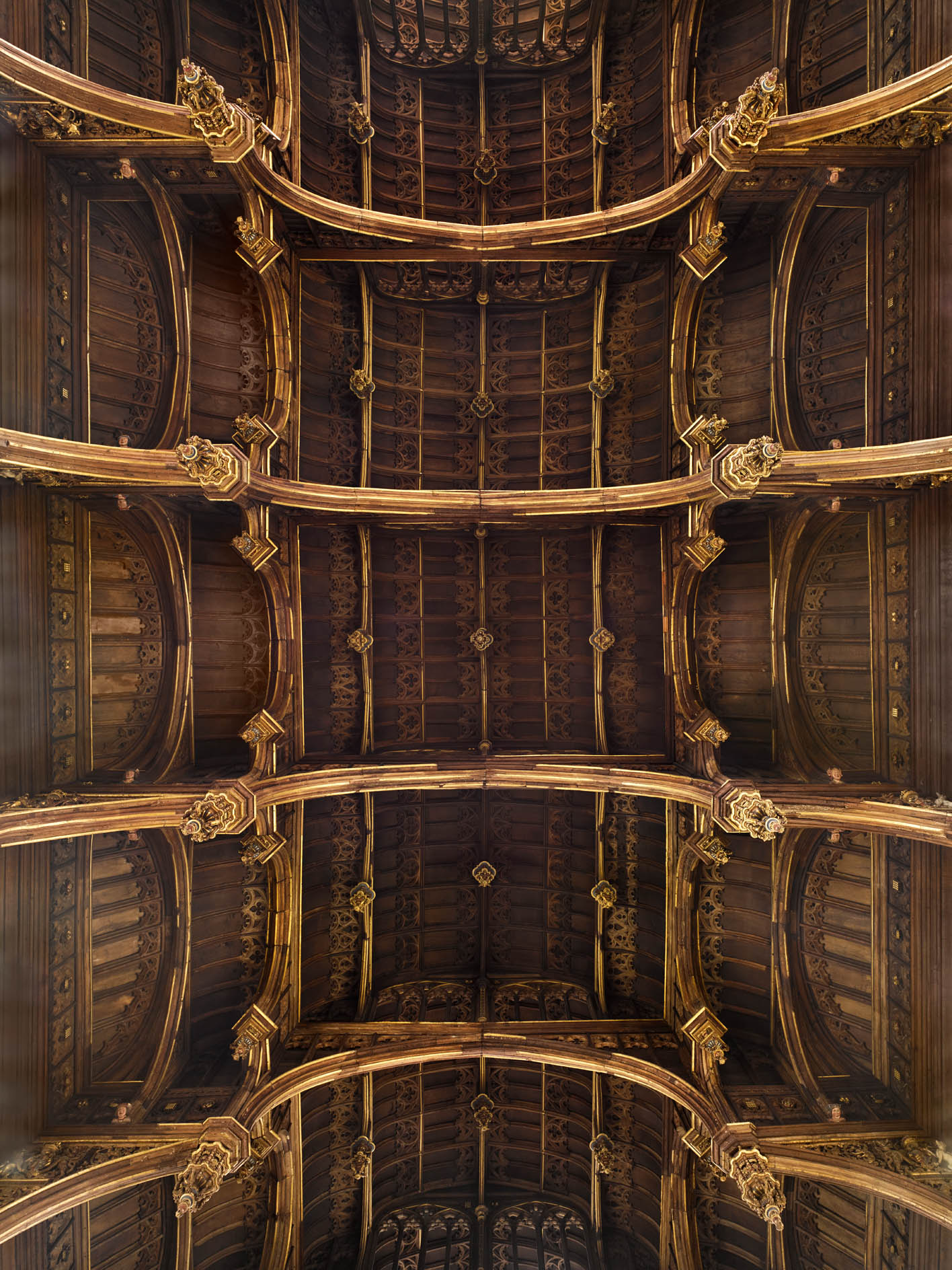

The modern visitor who climbs the stair from the middle gatehouse and walks into the great hall might be forgiven for thinking that they had stepped back in time. The Tudor interior with its spectacular roof seems perfectly preserved and the walls are hung with 16th-century tapestries depicting the story of Abraham.

For many centuries, tapestry remained the most expensive and luxurious wall covering in English domestic interiors and this particular set — heavy with gold thread — was commissioned by Henry VIII in 1537 from the Brussels workshop of Willem de Kempeneer. They were at Hampton Court by 1543–44 and almost certainly hung in this space on identifiable occasions, such as the reception of the Admiral of France in 1546. Their original brilliance has greatly faded, but a century later, in 1649, they were the single most expensive item in the entire art collection of the Crown, valued at a staggering £8,260.

Despite such authenticity of experience, however, the great hall is much more interesting than a mere survival. Rather, its fascinating story tells the tale of the palace as a whole. Our understanding of this owes a great deal to the work of Simon Thurley, whose important monograph Hampton Court (2003) constitutes the foundation for the present understanding of the development of the palace.

The architectural history of Hampton Court properly begins in the 15th century, when the manor was in the possession of the Knights Hospitallers. It stood in close proximity to the royal palace of Sheen, which was rebuilt first by Henry V and then by Henry VII, who renamed it Richmond. For this reason, the manor became desirable as a residence for courtiers and, in 1494, was leased out to Lord Daubeney. The courtyard house he knew and developed occupied the site of the present inner court and the position of its hall with kitchens to the north and a chapel to the east are still reflected in the layout of the Tudor palace.

In 1514, Cardinal Wolsey acquired Hampton Court and, under his supervision, it became by degrees a building of royal splendour. Wolsey added a new entrance or base court, completely redeveloped Lord Daubeney’s withdrawing apartments and created the present chapel (Country Life, November 12, 2014). It’s one mark of the sophistication of his patronage that he famously ornamented his buildings with roundels of Roman emperors by Giovanni da Maiano. As the poet John Skelton mockingly asked in about 1520, which court should you attend, the King’s Court or Hampton Court? ‘The King’s Court’ he observed ‘should have the excellence but Hampton Court hath the pre-eminence’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

By the end of 1527, the ‘King’s Great Matter’ of his divorce from Catherine of Aragon had placed the cardinal’s relationship with Henry VIII under strain and, in January 1529, Henry VIII, as part of wider appropriations of his property, took control of the palace and its building operations. Over the next decade and at the stupendous cost of about £46,000, he enlarged, repaired and improved the buildings. The progress of these huge works can be charted in surviving documentation, as well as in the varying dimensions of the millions of bricks used.

A small circle of royal craftsmen were engaged in oversight of the building work. There were two senior masons, John Moulton and Christopher Dickinson, and two senior carpenters, James Nedeham and William Clement. William succeeded James as King’s Master Carpenter in 1532 after the latter became Clerk and Surveyor of the King’s Works.

Lord Daubeney’s hall, which began to be demolished in 1532, was an early victim of Henry VIII’s aggrandisement of the palace. In the spring of the same year, six skins of parchment and four of vellum were purchased for drawing the designs of the new building. Nedeham clearly played a particularly important role in the work and even after his promotion was paid for riding from Westminster and spending 22 days ‘drawing of plats and making of moulds for the new hall’.

In many important respects, the design of the new hall at Hampton Court was pre-ordained. For time out of mind, any English residence of pretension had been entered through a chamber of exceptional size that was covered by an open timber roof and warmed by a central hearth. These were the spaces where, by long tradition, the entire household was fed and public festivities took place. The important thing about the new building, therefore, was that it was designed on an appropriately regal scale.

The new hall at Hampton Court was the last important building in this tradition erected by an English king. That was essentially because Henry VIII chose to assemble his vast and unwieldly household, and assume the protocol that attended it, only in a small group of major palaces (of which Hampton Court was one). When his Court was resident, the hall would have been intensively used. About 600 junior members of the household probably ate here in two sittings each day.

The plan of the building was entirely conventional, although the elevation of the hall above a vaulted undercroft was an unusual arrangement in England, where ground-floor halls were more common. There are nevertheless many important medieval precedents for this, as, for example, Richard II’s 1390s hall at Portchester, Hampshire, or the hall at Durham Castle in its various forms from the 11th century.

The main and service entrances were clustered at one end of the room and closed off from the main volume of the interior by a screen with two openings. At the opposite end of the hall was the dais, a privileged space defined by a step and lit by a projecting bay or oriel window. When it was being used for meals, the interior was furnished in the manner of a college hall with a high table across the dais and tables ranged lengthwise through the body of the room. This furniture would all be swept away for special events. On such occasions, the lower walls, which have a blank lower register, could be hung with tapestries.

In time-honoured tradition, however, the chief architectural glory of the hall interior was its roof, which was in the process of being covered in lead by the summer of 1533. The challenge of creating splendid hall roofs had been a spur to the invention of English master carpenters for centuries and this example is of a form unimaginable anywhere else in 16th-century Europe.

The roof is supported on projecting hammer beams, a form first turned to decorative account in the 1390s at Westminster Hall. The huge pendants were carved by one Richard Ridge. Pendants are not only found in such major hall interiors as Edward IV’s 1470s hall at Eltham, but in elaborate vaults of the period. It’s a curiosity of the Hampton Court roof that most of the subsidiary structural timbers are concealed beneath panelling, also an idea drawn from the treatment of vaults. As the nearby timber vault of Wolsey’s chapel illustrates, the masonry and carpentry traditions were inextricably linked.

Overlaying every element of the roof is a wealth of carved decoration, including figures, crests, heraldry and Renaissance motifs. Another London carver, Thomas Johnson, created the spandrels with royal arms and the initials of Anne Boleyn, by then Queen of England. The bills for the work reveal that the roof and its decoration was also painted — particularly striking would have been the decoration of the panels, with blue in evocation of the sky. In the spring of 1534, a richly decorated louvre or ‘femerell’ was added to the top of the roof.

The louvre was removed in 1663, but is shown in early views of the palace. It notionally stood over the position of the hall’s central hearth to let out smoke from the fire. Whether such a fire ever actually existed is an open question, but the inclusion of this detail underlines the conscious architectural archaism of halls, as fireplaces existed in grand English interiors by the 11th century. In the summer of 1534, Galyon Hones installed heraldic glass in the windows.

For the next century or more, the hall was a stage set for important occasions. It was also consistently admired by visitors and became a place where curiosities were displayed. In 1598, for example, the traveller Paul Hentzner described a looking glass, alabasters, portraits and a Bible that were shown to him here. As late as June 1662, the diarist John Evelyn simply described the hall as ‘a most magnificent room’. Forty years later in 1702, however, William III ordered that the interior be converted into a theatre. The work was interrupted when he died shortly afterwards, but it was completed by George I in 1717.

This may sound like a radical change, but the hall had long served as a setting for theatrical productions and the changes probably did little more than make permanent the kinds of temporary transformations it had undergone many times before. Added to which, it’s likely that the roof remained exposed (as the medieval roof over the busy law courts in Westminster Hall remained exposed). Certainly, enough was visible to inspire the fashionable architect William Kent to imagine the original interior in an engraving dedicated to the King in 1749. Antiquarian interest in Gothic architecture steadily increased and, in 1800, George IV directed the architect James Wyatt to remove the theatrical fixtures and repair the Tudor detailing.

Wyatt created a rather barren interior, but his work raised awareness of the building and laid the foundations for its next transformation between 1840 and 1846. In 1834, Edward Jesse became Deputy Surveyor of Royal Parks and Palaces. He was keenly interested in Gothic architecture and called on the services of his friend Rev John Mitford, editor of the Gentleman’s Magazine, ‘to evoke some of the atmosphere of the time of... Henry VIII’. It was helpful to Jesse as he struggled to get the necessary funds that Hampton Court had been successfully opened to the public for free in 1838 and that the hall was not initially accessible to visitors.

Under Jesse’s direction, the hall again became a monument to Henry VIII. Thomas Willement installed new stained-glass windows celebrating the descent of each of his wives from Edward I, as well as a related scheme of glass in the neighbouring Watching Chamber. Meanwhile, armour and hunting trophies were displayed on the walls. The former, since removed, were conceived by William Stacey, who had also worked on the 1820s displays of armour at the Tower of London. Perhaps Jesse’s most significant achievement, however, was to secure the Abraham tapestries for the interior in 1841. Finally, in conformity to the fashions of the moment, he also grained the roof to resemble natural wood.

Time and heavy use took their toll on the hall and, in 1922, a survey revealed serious structural defects with the roof. Recent repairs to the great halls at both Eltham Palace and Westminster had given the Ministry of Works experience with the problems of dealing with structures of this kind and a major restoration project ensued. The work was finally completed in April 1927, at a cost of £36,000. As part of this project, the stone floor of the hall was replaced with wooden boards and the 1840s graining of the roof was stripped away, together with the Tudor paint beneath it.

The great hall today is the opening interior of the tour of the Tudor rooms created by Historic Royal Palaces, which has managed Hampton Court since 1989. In a future article, we will examine the formal approaches to the royal apartments that superseded this great Tudor interior when Hampton Court was redeveloped as a Baroque palace.

For further information on Hampton Court, including opening hours, visit www.hrp.org.uk

The traditional Brick-Maker who supplies Hampton Court: 'It’s like kneading dough'

There is only one company left in Britain still producing hand-made bricks – and their customers include the likes of Hampton

A centuries-old altar cloth from a rural English church turned out to be the 'lost dress' of Elizabeth I, and it's set to go on public display

An altar cloth that turned out to be part of a gown belonging to Elizabeth I is going on display

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.