Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Martin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As inventive as a Chancellor of the Exchequer might be in finding new ways of raising taxable revenue, there will be others determined to find ways to minimise its impact. Perhaps the classic example is the story of a tax that gave rise to the phrase ‘daylight robbery’ and whose effects can be seen on British buildings to this day, even though it was abolished over 170 years ago.

During the 17th century the intrinsic value of the silver and gold in British coinage was greater than the nominal value of the coin itself, encouraging many to engage in coin clipping, slicing off slithers of coinage to melt down and make counterfeit coins. Despite being a treasonable offence punishable by death, the practice was so rife that according to Lord Macauley, at its peak, only one coin in every two thousand was genuine, destabilising confidence in the British currency and losing valuable income for the Treasury.

In 1696 William III embarked upon an ambitious programme, known as the Great Recoinage, of issuing £7 million of new coinage and withdrawing the debased coins from circulation. Appointed as Warden of the Mint, Sir Isaac Newton improved the efficiency of the Mint by increasing the number of smelting furnaces and using rolling mills powered by horses. Despite the success of the scheme, there were areas of the country where old coinage was still in circulation, enabling coin clipping gangs to operate well into the 18th century. The exploits of one such, the Cragg Valley Coiners, were recently the subject of a TV adaptation of Ben Myers’ novel, The Gallows Pole (2017)

As well as the Great Recoinage, 1696 saw the passing of the ‘Act of Making Good the Deficiency of the Clipped Money’, which introduced a tax on windows. In an age when delving into the particulars of a person’s wealth was deemed to be an affront to their liberty, the authorities used visible and tangible assets as the basis of taxation. Given the expense of glass and the difficulty in producing large panes, the number of glazed windows was seen as an indicator of relative wealth.

Levied on occupiers rather than owners, there were two elements to the tax, a flat-rate of two shillings and then an additional charge dependent upon the number of windows. Properties with between ten and twenty windows were charged an additional four shillings and eight shillings was levied on those with more than twenty.

Over the next century the basis for calculating the tax was altered, a top rate of 20 shillings introduced in 1709 for buildings with thirty or more windows and in 1747 the flat-rate was abolished in favour of a variable rate based on the value of the property, a concept that still remains today with Council Tax. Each window on properties with ten or more windows was charged at 6d a window, rising to 9d a window for those with between fifteen and nineteen windows, and one shilling a window for twenty or more. The top rate was increased to three shillings a window in 1758 and in 1766 the threshold for the charge on individual windows was reduced to seven.

"When William Pitt tripled the rate of the window tax in 1797, thousands of windows were bricked or boarded up overnight"

All industrial and retail buildings, cottages occupied by those who were too poor to pay poor or church rates, and ‘service and business premises attached to dwellings’ were exempt as were windows to rooms which were not lived in, such as dairies, cheese rooms, and milkhouses. Occupiers often carved the purpose of the room on the lintel of the window to aid identification.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Naturally, the new tax led to feverish efforts to identify and exploit loopholes in the legislation, aided and abetted with a little bribery of the local assessors. Some would arrange ‘a few sacks of corn or a little Lumber’ around a room or two in an attempt to convince the assessor that it was not lived in and, therefore, exempt, some, with the connivance of local officials, claimed to be too poor to be liable, and others simply resorted to force, refusing assessors the right to entry and threatening them ‘at the Peril of their lives if they attempted it’.

Just as blocking up chimneys was seen as a legitimate way to reduce the impact of the Hearth Tax in the 17th century, so blocking up windows became an accepted practice, one so rife that it was described in a 1747 report to Parliament entitled ‘relating to the Difficulties and Obstructions which have attended the Collection of the Duties on Houses, Windows, and Lights as ‘the greatest Prejudice to this Revenue’.

Initially, windows were blocked on a temporary basis, ‘done only’, the report noted, ‘with Bricks or Boards, which may be removed at Pleasure, or with Mud, Cow-dung, Mortar, and Reeds, on the Outside, which are soon washed off with a Shower of Rain, or with Paper or Plasterboard on the Inside’. As soon as the assessor left the area, the temporary boarding was removed, leaving the resident free to enjoy the light from the window without having paid any tax for the pleasure.

Over time, with the government exacting fines on anyone reopening an unassessed blocked-up window and the development of a more professional and centralised tax collection system, windows were blocked off permanently with bricks, creating blind or dummy windows. New builds were designed with just enough windows to meet the minimum tax thresholds of nine, fourteen, or nineteen. Alternatively, as a group of windows separated by twelve inches or less was counted as one window, some buildings were built with long rows of adjacent windows.

When William Pitt tripled the rate of the window tax in 1797 in response to the need to raise revenues to counter the Napoleonic threat, thousands of windows were bricked or boarded up overnight. The President of the Society of Carpenters told Parliament that almost every homeowner in London’s Compton Street had contacted him to reduce the number of windows in their property as a matter of urgency.

Two statistics graphically show the extent of window blocking. By 1726 the amount of revenue raised by the tax was around £100,000 less than it had been between 1703 and 1709. In 1851, despite the exponential growth of the population and the impact of the Industrial Revolution, glass production was at the same level as it was in 1810.

As an independent country in 1696, Scotland was spared the window tax until William Pitt extended its reach in 1784. In response, the Scots became enthusiastic window blockers, many buildings bearing the tell-tale signs of frames infilled with bricks, which came to be known as ‘Pitt’s pictures’.

During the 19th century there was a growing recognition that damp, overcrowded, and unlit housing was injurious to public health. Charles Dickens weighed in to help the campaign to abolish the tax, telling Parliament in 1850 that ‘we are obliged to pay for what nature lavishly supplies to us all, at so much per window per year; and the poor who cannot afford the expense are stinted in two of the most urgent necessities of life’.

The campaign was so successful that the tax was abolished on July 24, 1851, a move marked by a cartoon in Punch magazine in which a family welcome the arrival of a smiling sun through their new window. Pitt’s pictures can still be seen, a reminder of a tax that really was daylight robbery.

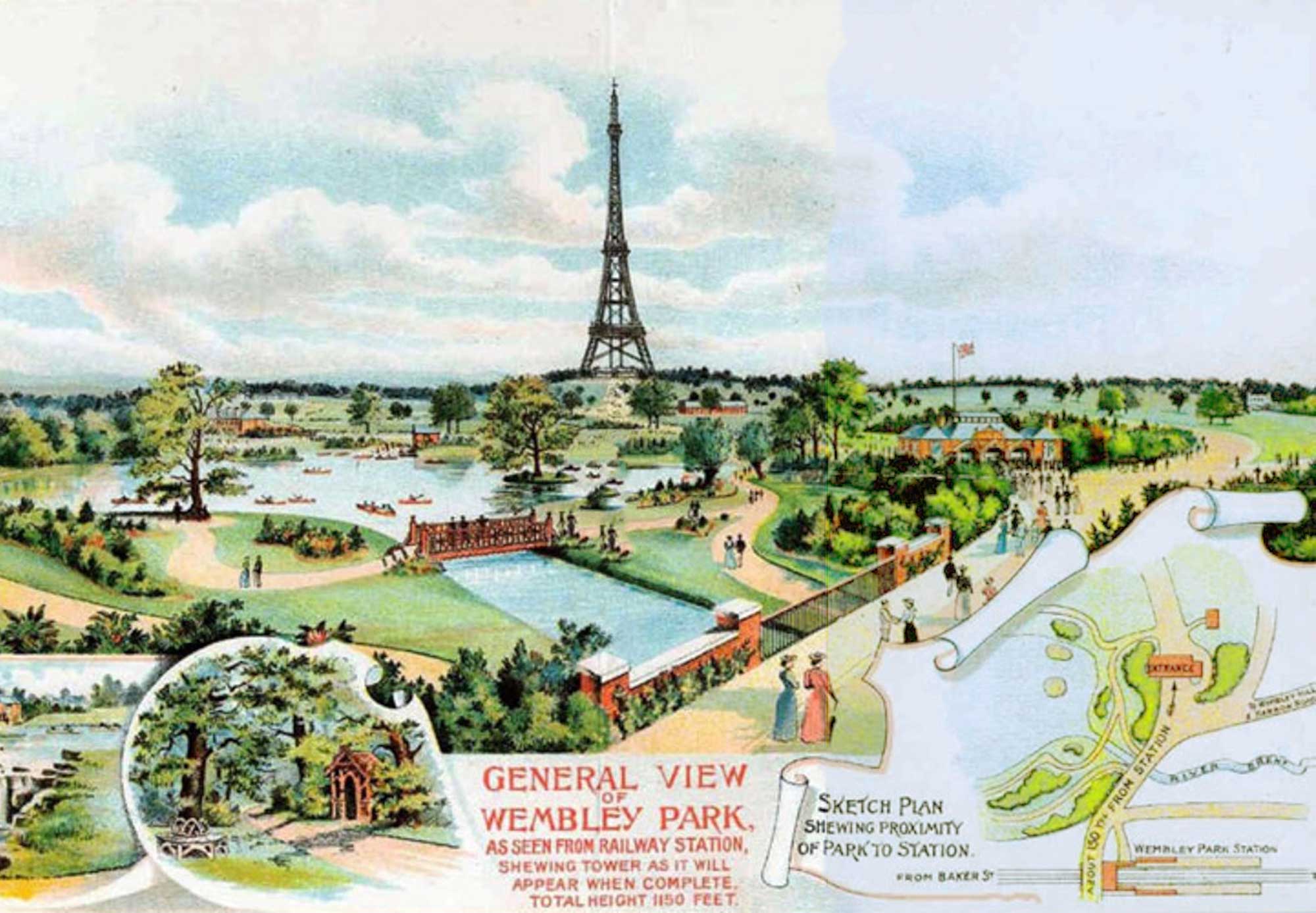

How London nearly had its own Eiffel Tower

England and France competed fiercely for bragging rights in the 19th and early 20th centuries — but no version of France's

How Alexandra Palace has survived fires, bankruptcy and even gang warfare in 150 years as London's 'palace of the people'

Alexandra Palace has suffered every imaginable disaster, yet remains enduringly popular even a century and a half after its official

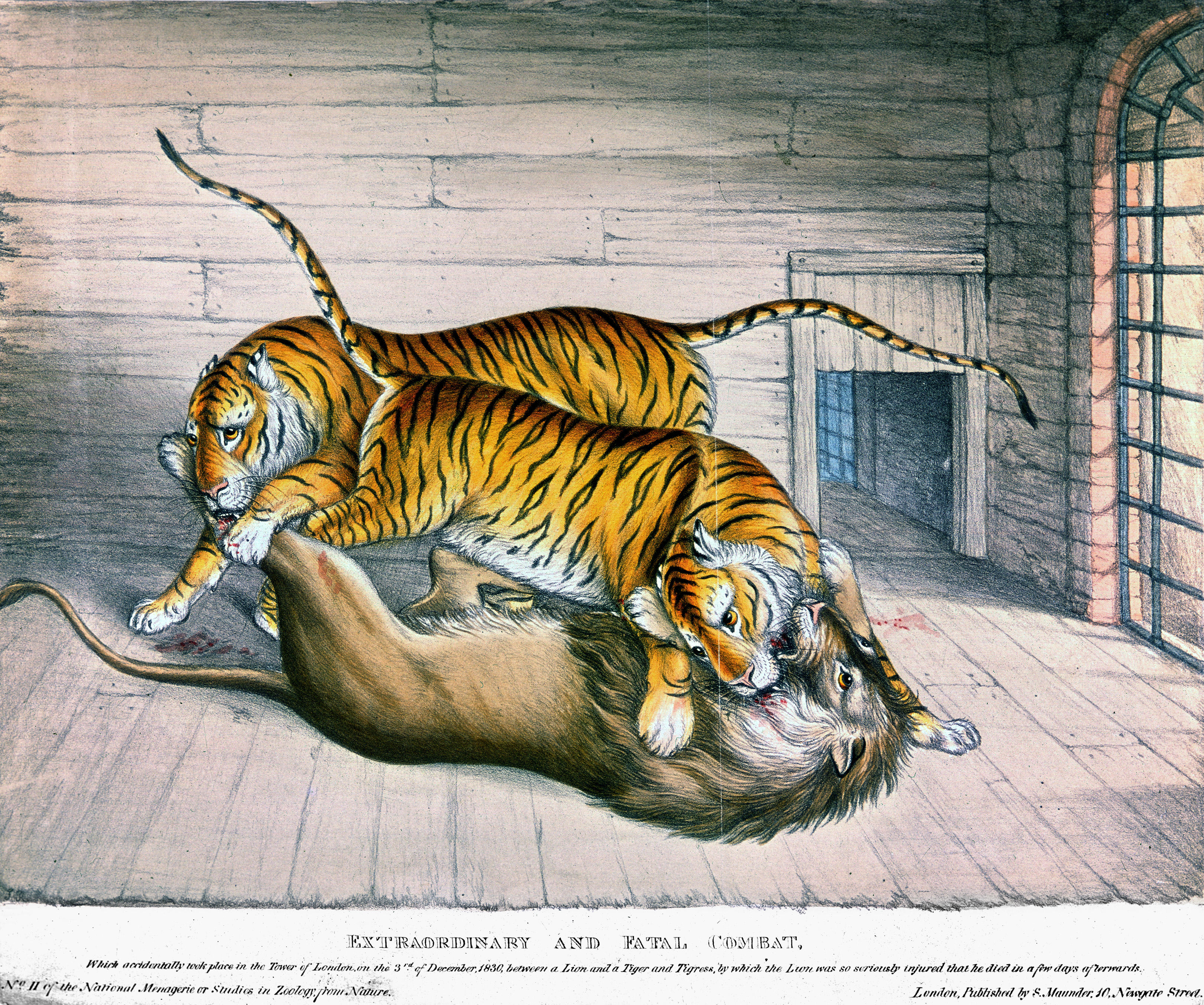

Curious Questions: Did the Tower of London menagerie provide the animals for London Zoo?

Wolves in the Tower of London and an elephant so well trained that Lord Byron wanted to adopt it as

Curious Questions: When does summer actually start?

You'd think it would be simple. It's anything but, as Martin Fone discovers.

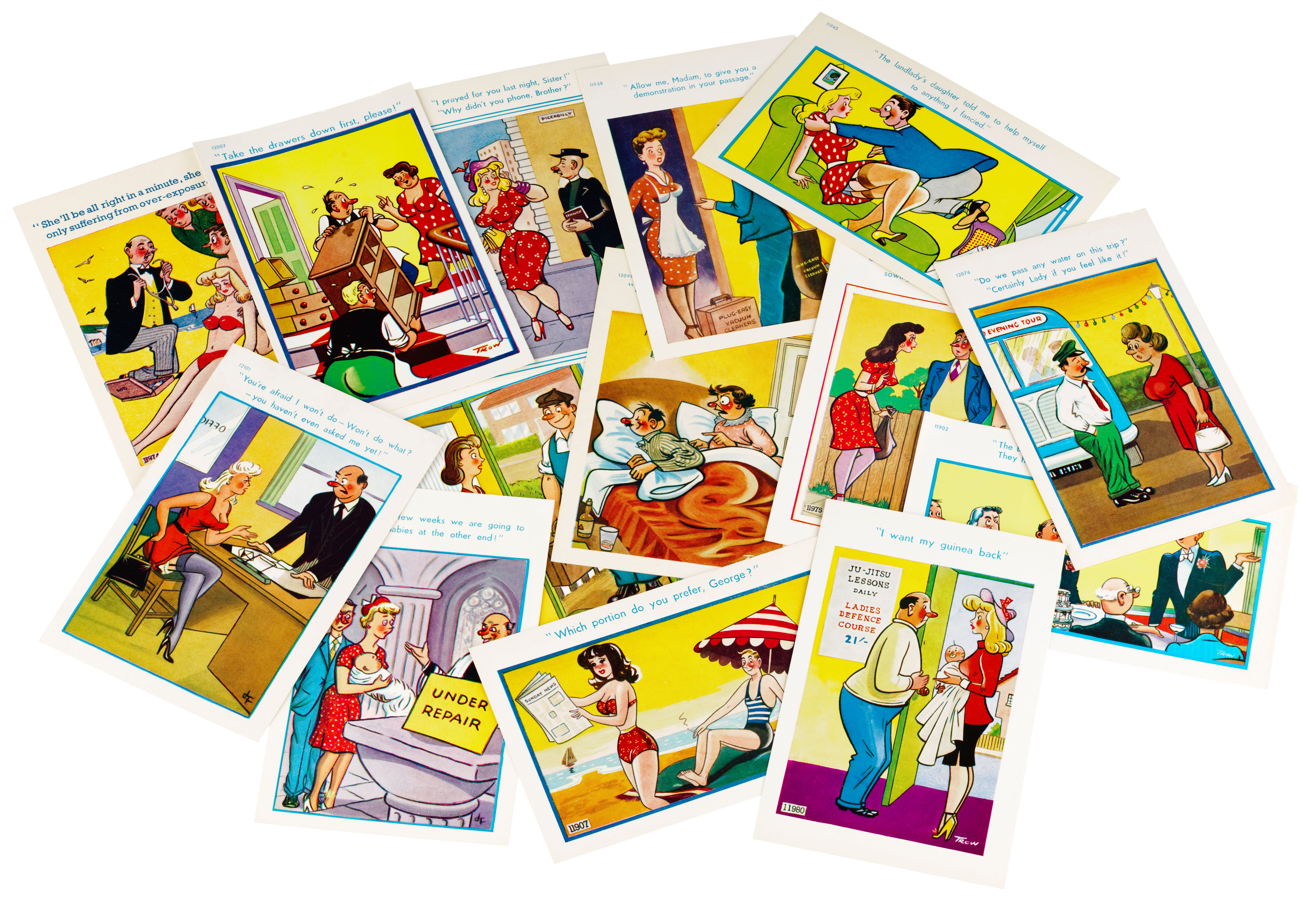

Whatever happened to saucy seaside postcards?

Saucy seaside postcards were once a mainstay of British life over the summer, but these days they're rarely seen. Martin

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.