Jason Goodwin: 'All he had to do is walk along the same street in his mind and sing out the objects as they cropped up'

Our Spectator columnist discusses the psychology of the individual, ‘The Bloody Fool Theory’ and culturally-specific syndromes.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It all comes down, as Jeeves often remarks, to the psychology of the individual. Years of patient study has convinced me, for instance, that my sister and my father share a weakness for gadgetry.

His manifests in a Heath Robinson arrangement of computer screens, wires, USB adapters, hard drives and a spaghetti of wires and plugs. Hers is embodied in the Thermomix, a kitchen aid that can cook, chop, grind and mince. It will make a béchamel or a carrot cake and comes from Germany, where housewives presumably have a lot of time to study the instruction booklet.

They both love e-bikes, orthopaedic chairs and Roberts radios. For his 85th birthday recently, she bought him a pair of dark glasses with hidden speakers that connect to the music in his mobile phone and play it secretly, just behind his ears, through the bones in his head.

One of his granddaughters remarked, rather sniffily, that they were the kind of thing you’d find in a duty-free shop at the airport. Exactly. He was as happy with them as Eeyore with his popped balloon and a jam jar.

I have been taking an interest in all this ever since another of his granddaughters decided to apply to read psychology at university. Now, the house is full of entertaining books about the way other people’s minds work, which I enjoy reading in bed or on the train.

'The primary symptom of piblokto is screaming and running uncontrollably through snow'

A. R. Luria, a Soviet psychologist, wrote The Mind of a Mnemonist about a man with a depthless memory. S, as he is called in the book, not only recalled long lists word for word – he could still regurgitate the list, without warning, years afterwards. I can forget anything, from my friends’ names to the vital ingredient at the supermarket, so I naturally find this book compelling. S has a form of synaesthesia, which turns every sound he hears into a vivid visual image. Give him a list of words and he would mentally walk along a familiar street, distributing the shapes of the words – or the numbers or sounds – in different places. Then all he had to do is walk along the same street in his mind and sing out the objects as they cropped up.

There is much more about S in this vein, but the point is that Luria was the first truly kindly psychologist, a ‘romantic scientist’ who went out of his way to consider S as a fellow human being, not a freak, with gifts and disabilities like the rest of us.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

S suffered from an inability to forget, a complete synaesthetic overload when it came to reading poetry and a funny feeling when he heard the word ‘zhuk’.

The Penguin Dictionary of Psychology also makes good bedtime reading. I like to drift off thinking about piblokto, for example, ‘a culture-specific syndrome found among Eskimos. The primary symptom is an acute attack of screaming and crying and running uncontrollably through the snow’.

In The Oxford Companion to the Mind, I came across a detailed entry for ‘Military Incompetence’ as a syndrome. We’ve got better at most complex things so why, after 2,000 years or more of practice, are generals still so bad at waging war? It’s not because they are stupid (also known as ‘The Bloody Fool Theory’): incompetence is not exhibited at random through the history of war.

Studies have been made linking ‘the retreat from Kabul in the first Afghan War; episodes in the Crimean war; the Franco-Prussian war, the Indian mutiny and Boer wars’, and so on, down to the siege of Dien Bien Phu and the Bay of Pigs fiasco. I’m sure we could name modern examples. The explanations are complex and astounding. Jeeves, as usual, was right.

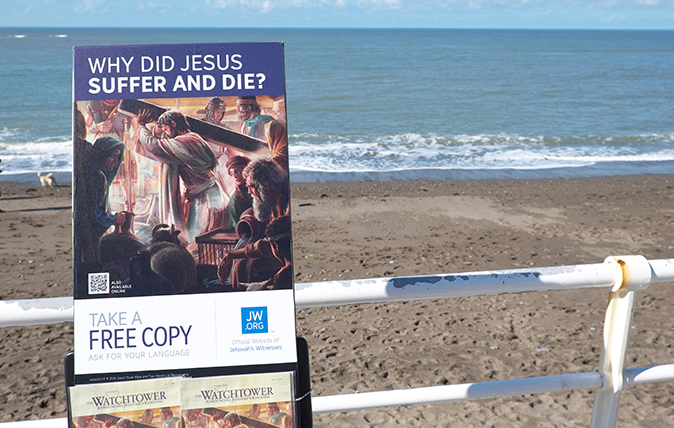

Jason Goodwin: Keeping up with the Jehovahs

'I don’t get into theological debate with them; I simply like to bask awhile in their radiant happiness'

Perfect pilaf rice made simple: A skill that every cook should learn for life

Writer, historian and chef Jason Goodwin whips up perfect pilaf rice.

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: On wardrobes, spontaneous combustion and burning Vladimir Putin

Our columnist takes his life into his own hands by witnessing the ceremonial destruction of Russian premier Vladimir Putin.

Credit: Getty

Jason Goodwin: 'There was nothing there. The original message from St Petersburg, Sergei’s emails, the thank-you email. All gone.'

Our columnist Jason Goodwin recounts a chilling tale of his own brush with the Russians in Dorset.