Why you shouldn’t fear eating offal — it's food 'to soothe, comfort and delight'

Sustainable eating means cutting waste — and that means using the whole animal. Yet it’s nothing that should make you feel squeamish, says Tom Parker-Bowles.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Parsimony and pleasure: two words that aren’t exactly the most natural of bedfellows. However, when it comes to offal and those more thrifty cuts of meat, it’s a truly joyous union. Cheap, nutritious and verging on the divine, these blessed bits and bobs are far removed from the bland iniquities of arid chicken breast, the po-faced predictability of fillet steak. They offer deep flavour, pure succour and true culinary thrills, plus a veritable riot of textures.

If we are going to eat beasts, it’s only right and proper to ensure we don’t waste one tiny scrap. Not a novel notion, I know, and one that kept civilisation fed for millennia. But in this unthinkingly throwaway age, it’s more important than ever to embrace the whole beast, nose to tail, snout and pout. Yet all too often, these jewels in the carnivorous crown are scorned and ignored, looked down upon, sullied or downright feared.

School food doesn’t help. It never does. Hideous memories of wan, gristly flaps of ox liver, riddled with tubes, that were the mainstay of our Wednesday lunch. Truly depraved, they formed a dish you wouldn’t wish upon your worst enemy. The trick was to slip them into your pocket to be disposed of later.

Or kidneys, bullet hard, with an assuredly uric tang, that polluted — alongside fatty, improperly cooked stewing steak — a particularly wretched pie.

When it comes to all things internal, the names hardly trip lyrically off the tongue: offal, guts, organs, variety meat. Hardly the most attractive of terms, blunt, bloody and brutal. It’s not only the descriptions that repel, but rather our innate fear of the unknown — the sinister, alien whispers of the wobbly and squidgily scary.

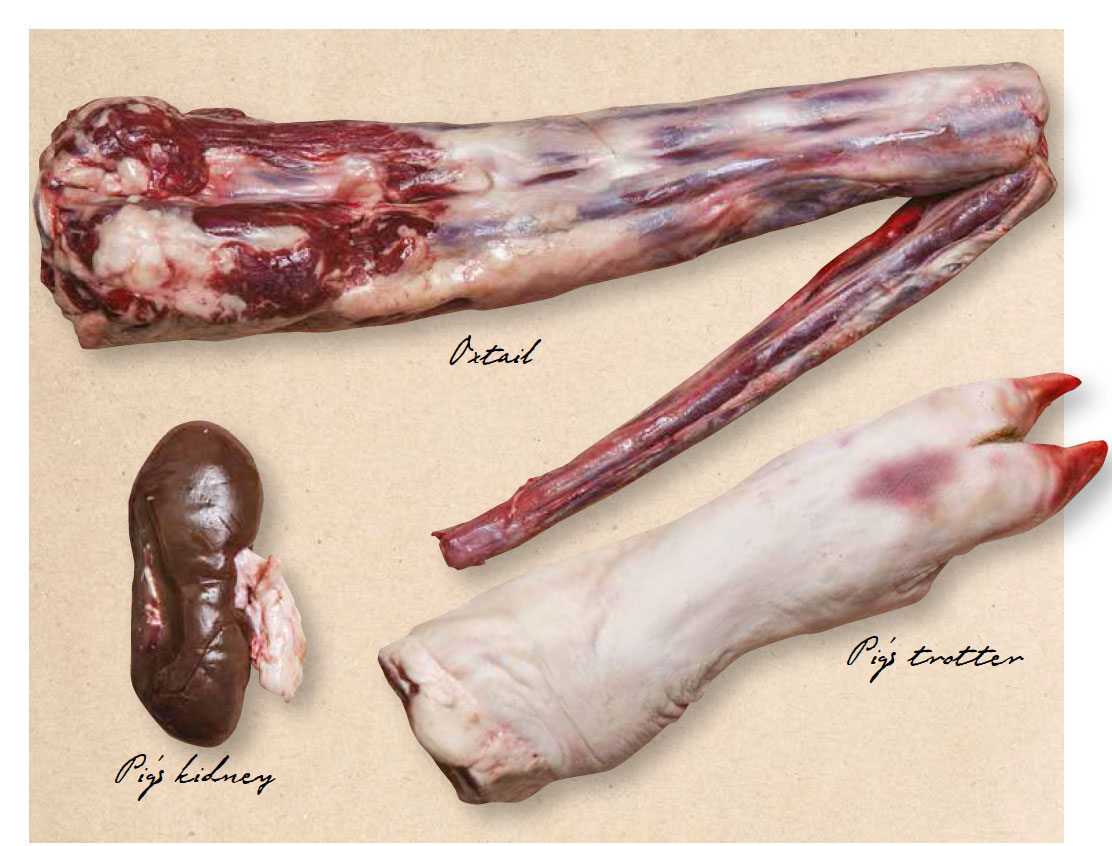

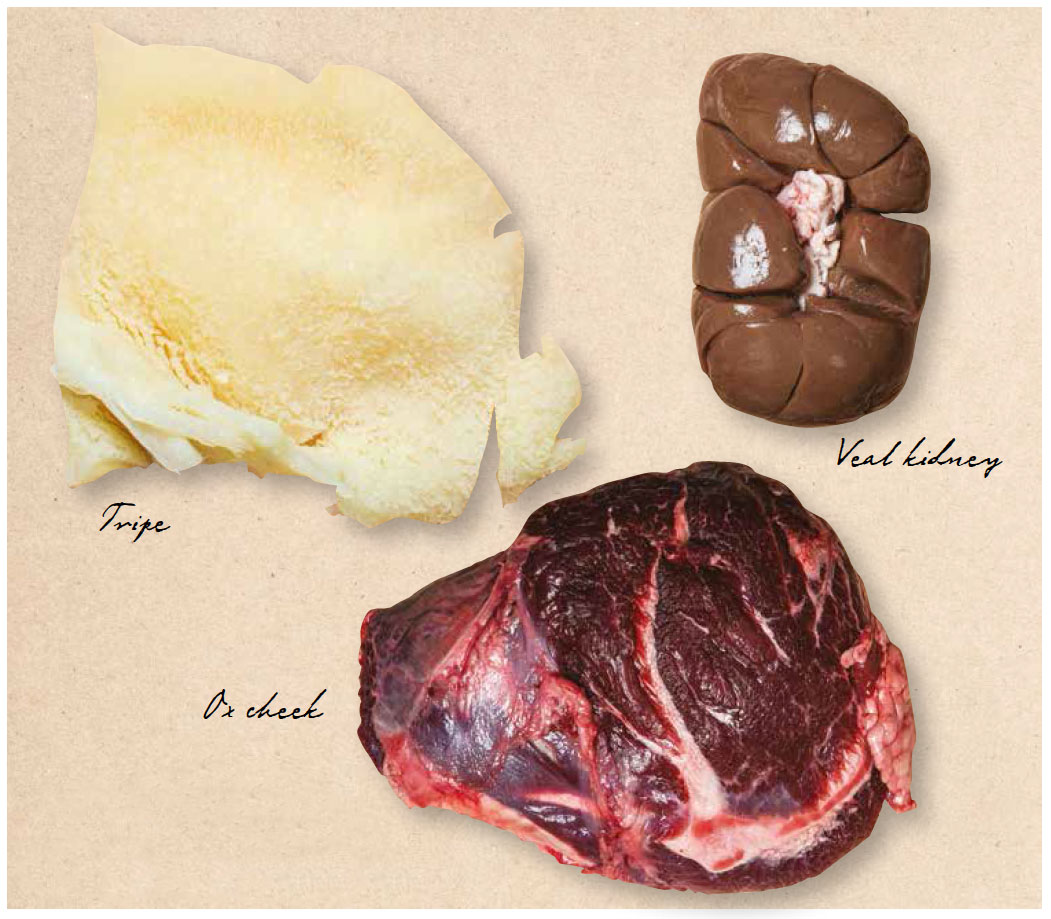

However, it’s exactly those textures that make offal so appealing. In most of the great food cultures, texture (or hau gum, mouth-feel in Chinese) is every bit the equal of taste. The cartilaginous crunch of tendon or ear, the bounce of kidney, tripe’s tender chew. These are things to be craved and worshipped rather than abhorred and despised. Offal isn’t about some macho form of extreme eating, visceral kicks for the very drunk or dumb. These are bits to soothe, comfort and delight.

As Fergus Henderson, the man behind London’s St John restaurant and the high priest of ’umbles, so rightly points out: ‘Nose-to-tail eating is not a bloodlust, testosterone-fuelled offal hunt. It’s common sense and it’s all good stuff.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It sure is. How do I love thee? Let me count the ways. Oxtail stew, soft as a sigh, with a great mound of buttery mashed potato. Brains, lavishly creamy and oh so delicate, lightly dusted with flour, fried in butter, then served with beurre noisette, lemon and capers. Devilled kidneys, pert and just pink, those cayenne- and mustard-spiked juices soaking deep into thick brown toast.

Tongue, sliced thin, with sauce gribiche. Brawn, in a pellucid, parsley-spiked jelly and pig’s-head croquettes. Yakitori chicken hearts, fresh from the coals. The liverish chew of bavette. Menudo, or Mexican tripe stew, a fiery hangover cure of some magnificence.

Sweetbreads, gently burnished and studded with slivers of black truffle. Grilled ox heart with pickled walnuts and horseradish, akin to the rich and most regal of steaks.

'If you’re going to kill the animal, it seems only polite to use the whole blessed thing'

Dishes can be as complexly classical as Pierre Koffman’s stuffed pig’s trotters or as blissfully simple as a roast chicken oyster, sneaked from the carcass as a true cook’s treat. Far from being the off-cuts, they’re the stars, ingredients that are rightly revered in most cultures, but rather disdained by us.

When it comes to cheaper cuts, breast of lamb or skirt steak, ox cheek, knuckle of pork, ribs or tail, there’s something magical in transforming tough, unyielding raw flesh into a morsel you could cut with a spoon. They may not crave the fast heat of the pan, but tuck them in to braise or stew, go slow and low, and that unforgiving collagen will be coaxed, oh so gently, into luscious, lovely gelatin.

Shin of beef is only the start. Breast of lamb Sainte Ménéhould, that Elizabeth David favourite, braised, deboned, sliced, bread-crumbed and baked. Bliss. And did I mention those stews and braises?

Okay, so I’ve come across dishes on my travels that would test even the most visceral of palates. Raw tripe salad in Laos, more porcine chewing gum than decent dinner. Eating with a lovely local family, there was no way I could leave a scrap. Squeak, squeak, squeak it went, as I tried, gamely, to swallow the damned stuff and grin at the same time. There’s texture and there’s just too much.

Tripe, usually one of the four stomachs of a cow, is perhaps the most difficult and divisive of all offal types. I love to eat it in modest amounts, cut into small pieces. The flavour is subtle (especially when it’s been bleached), but definitely hints at the more feral side of the beast.

In dishes such as Claude Bosi’s gratin of tripe and cuttlefish at Bibendum, it becomes a soft, slippery work of art. The same for Andrew Wong’s spiced Sichuan version at A. Wong, where it’s cut into tiny slivers. Or Simon Hopkinson’s Chinese tripe, fragrant with star anise and chilli. If you ask him very nicely, he might send you a pot.

My friend Manoli’s mother makes a special Greek Easter soup, fragrant with herbs and lemon. The tripe is cut into small, postage-stamp-sized mouthfuls. That classic northern dish, tripe and onions, is, however, one step too far. Too bland, too much tripe.

Andouillettes, those intestine-stuffed French sausages that wear the stench of the sewer, can be tricky. No amount of mustard can mask their rank lavatorial reek. I want to love them, really I do, however, at the likes of Chez Georges in Paris or Brasserie Georges in Lyon, I’ll always back down and slink towards the less brutal charms of rognons d’agneau à la dijonnaise.

Equally testing was lu, or cold blood soup, supped at a truck stop in northern Thailand. I certainly wouldn’t have ordered it if eating alone, but I was in the company of some great Thai chefs and, well, it would have seemed churlish — not to mention unadventurous — to say no. The spicing was fierce, but that ferric tang unmistakeable. Raw pig’s blood is definitely an acquired taste, although proper black pudding, made with the fresh stuff, is a sausage of true beauty.

'It’s only really the UK and the USA that turn up their noses at such things. Which seems idiotic'

I’m not certain that taco de ojo, or cow-eyeball taco, will appeal to many, but eaten in a Mexico City market and smothered with lime, pico-de-gallo salsa, hot sauce and avocado, anything is palatable. Again, you’re after that gelatinous texture.

The Mexicans, as with any other strong food culture, value and adore offal and cheap cuts. What serious cook doesn’t? Eating the cheap bits may have been born out of necessity (the poor could seldom afford prime cuts), but quickly turned into a genuine passion.

In fact, it’s only really the UK and the USA that turn up their noses at such things. Which seems idiotic. As the food writer and true offal aficionado Matthew Fort points out: ‘Forget about parsimony! Offal is extremely digestible and extremely nutritious. Offal is the food of the Gods.’

Once again, trust your butcher. I’ve never known one who didn’t delight in the more obscure parts of the beast, because that’s where the real flavour is. Better still, eat well and salve your conscience. As Mr Henderson so rightly declares: ‘If you’re going to kill the animal, it seems only polite to use the whole blessed thing.’

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Tom Parker-Bowles: Why a well-stocked larder is a very splendid thing, and the building block for 1,000 dishes

A well-stocked store cupboard is an essential of British life in the 21st century, says Tom Parker-Bowles as he reveals

Credit: Graham Day / Getty

In praise of the great British sausage – and five of the best bangers you can buy

Few foods are equally at home on the tables of royalty as they are at the local greasy spoon, but

Tom Parker Bowles is food writer, critic and regular contributor to Country Life.