In Focus: Lucian Freud's plant portraits, from the tiny to the vast, all years in the painting

Steven Desmond visits the Lucian Freud exhibition at the Garden Museum, bringing a horticulturalist's eye to works by one of Britain's great 20th century artists.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Let me be clear at the outset: Lucian Freud was not a botanical artist. He was a very great artist who sometimes painted plants. This is a little-known fact and one we should consider carefully. Everyone can now readily form their own opinion on the matter, as the Garden Museum in London is presently hosting an exhibition of Freud’s plant portraits, which runs until next March.

I first encountered Lucian Freud’s work when I was a schoolboy in the 1970s. With a bit of time to kill, I looked into a museum in which that day was a touring exhibition of his portraits. I knew nothing of such things, but was immediately convinced.

Having spent my working life in horticulture, I have always been politely interested in pictures of plants and, as does everyone else, I know what I like. This does not make me an art critic. When I learned that there was to be a centenary exhibition of Freud’s paintings of plants, I was pleasantly surprised and wondered what they might look like. I imagined they might embody that fierce, searching realism we all know from his images of humans.

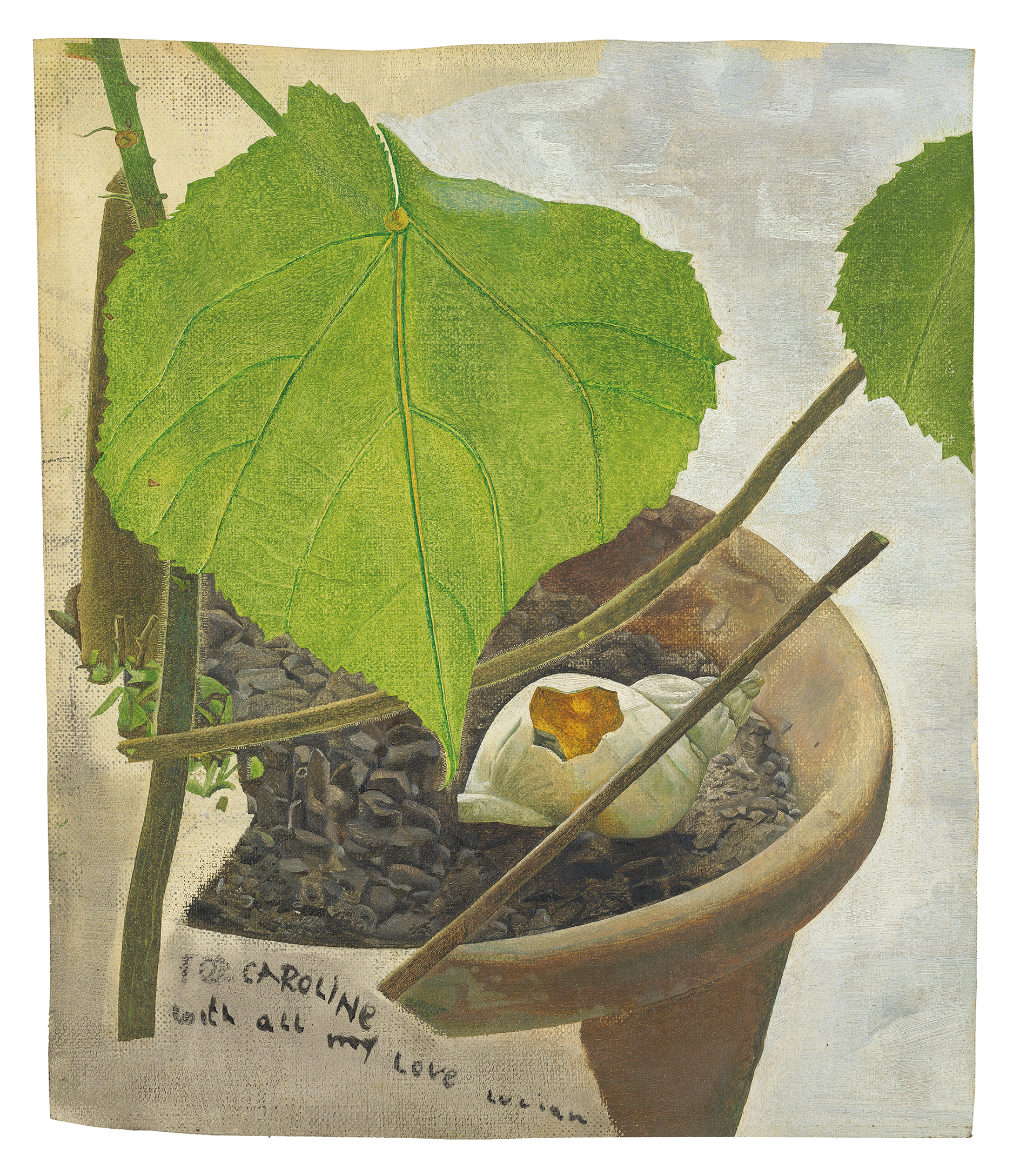

I was right. The big surprise to me is how different they all are. This is not obvious from reproductions on the printed page. Some are huge, others tiny. Most are in oil, but others are in charcoal, complete in themselves. Most are on canvas, but some are murals on a giant scale. Some are of beautiful flowers and fruits, but others are cropped snapshots of shrubs and pot plants in scenes verging on dereliction. It is impossible to identify a style or a manner, which must make them difficult to attribute.

Freud came perforce to Britain as a child in 1933 and essentially got nowhere until, at 17, he joined Cedric Morris’s school for painters in rural Suffolk. This was the turning point. Freud said himself that ‘Cedric taught me how to paint, and more importantly to keep at it’.

I found myself wondering how interested in plants Freud actually was. He always had pot plants, increasingly drawn and grim-looking with time, as he never attended to their needs. His assistant David Dawson said ‘he planted things and let them grow, grow and grow. He never touched anything’. He was no gardener.

"The plant portraits here are always meticulous, whether of a giant cyclamen on a wall or a tiny image of a lemon sprig"

The garden plants steadily out-grew their intended space and reached up to the second-floor windows. Freud was untroubled by this and painted cropped sections of what he saw, sometimes of giant, sprawling, seedling buddleias, the sort that adorn railway lines and failing parapets. As did Eliot Hodgkin, he drew attention to things we routinely overlook.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The plant portraits here are always meticulous, whether of a giant cyclamen on a wall or a tiny image of a lemon sprig. They are very accurately observed, so, in that sense, they are botanical. Sometimes, the paint is chunky and spiky, but usually it is perfectly flat and radiates calm order. He always took his time. His pictures took more than a year to complete and, in the case of one of my favourites, the enormous Two Plants, three years. This, of course, had to account for the growth of the plant over that time.

I was interested to discover that Freud admired the work of Constable, in whose honour there is a charcoal drawing of a tree trunk, and of Monet, whose garden at Giverny he revered. He also recalled a print of Dürer’s Great Piece of Turf, of 1503, on his parents’ wall in Berlin. It happens that I love that work, too, which always helps.

Two paintings, in entirely different styles, stick in my mind. One is a fruiting banana painted at Ian Fleming’s Goldeneye estate in 1953, thrillingly realistic, and the other the grave of Freud’s beloved dog Pluto next to an overgrown buddleia of 2003. Each tells the story of that moment in Freud’s unnervingly rackety life.

This is not a large exhibition and anyone can walk around it in a few moments. It is, however, well organised and so full of good things that I recommend it without hesitation. Freud was not afraid to discuss his paintings and once said he hoped that, if he concentrated enough, ‘the intensity of the scrutiny alone would force life into the picture’. It did.

The Garden Museum’s Lucian Freud exhibition runs until March 2023 — see gardenmuseum.org.uk for more details.