Exhibition review: What is Luxury? at the V&A

Beyond bling.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What is Luxury?’, asks the show now occupying the central exhibition space in the V&A. It’s a timely question. Although, to many people, the answer might be obvious— a bit more than they have at the moment—we also live in an age of ultimate possibility, financially at least. Income levels have pulled apart and the very rich are now billionaires. Naturally, the sales of luxury goods are booming. The growl of the supercar, the pop of the Louis Roederer Cristal cork and the whirr of the cash machine are the (metropolitan) noises of the age.

But the curators of this show invite us to look beyond the obvious. People to whom Prada and Louis Vuitton represent the height of aspiration will be awakened to the glories of the human spirit in its quest to tempt the consumer with ever new and more wonderful stuff. Some of the pieces are incredible. If I hadn’t actually seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it was possible to make a chandelier using dandelion clocks—with a tiny LED light in the middle of each seed head. That surely meets a definition of luxury familiar to some households: the quality of being easily broken.

Rumpelstiltskin spun straw into gold; Giovanni Corvaja has performed an almost equally impossible feat by weaving gold thread into a hat. Although the technique of enriching tapestry with gold thread was familiar to the Renaissance, nobody, apparently, has thought of using it for a headpiece before. Sig Corvaja spent 2,500 hours on the project, which uses 160km (100 miles) of superfine 22-carat and 18-carat gold thread.

Nora Fok has used much more humdrum materials to make her Bubble Bath necklace: toy marbles and nylon filament. But each marble has been wrapped in an infinitely delicate covering that has, astonishingly, been micro-knitted to fit. The effect is other-worldly, like the bubbles that might collect around an underwater wreck.

Chung Hae-Cho makes cups from lacquer—and nothing but lacquer (except a little fabric around which it adheres). Usually, lacquer is applied to wood; the artist has invented a process for using it practically neat.

I don’t know which awes me more—the imagination of the craftsmen in conceiving such work, the patience with which they have pursued their ends or the technical ingenuity needed to make it.

Contemporary objects are contrasted with a selection of cleverly chosen objects from other epochs that exemplify traditional aspects of luxury. A chasuble from Venice demonstrates the consummate skill of 17th-century needleworkers, who could turn simple linen thread into a ravishing lace filigree of scrolling flowers. A silver-covered howdah from India of about 1840 is the only piece in the show to interpret luxury as pure swank. A jewel-encrusted gold crown from 18th-century Portugal—well, it’s a crown.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Notice that all these pieces were made to be used, which surely heightens their luxuriousness. It’s one thing to own a fabulous object, but how much more splendid to get the piece out of its tissue paper, whether for an elephant ride or a church service.

In association with the Crafts Council, the show necessarily has a focus on objects. I liked most of them, from the gold-leaf-coated skimming stone to the exquisite briefcase, its leather surfaces decorated with swallows and flower garlands. Strangely, however, I didn’t feel that actually owning any of them would add greatly to my life—which made me wonder if they were true luxuries. To that question were added others in the second half of the show. What if, by 2052, plastic becomes a precious material? What if a vending machine could supply biological data on demand from a sample of our saliva?

Interesting perhaps, but they seemed to miss a trick about the nature of luxury today. One definition of it must be the life-enriching experiences that are most difficult to find. Pre-industrial societies wanted to keep warm, eat well and show off, so fur-lined robes, spices and gold plate were among obvious luxuries. Our 21st-century priorities are different. The meanest of houses have central heating, we eat too much and the most sophisticated consumers are ‘moving beyond bling’.

That comment was made to me on the opening night by Niccolò Barattieri di San Pietro, head of the property company Northacre, which sponsored the show; ‘the international rich increasingly want authenticity, rather than instant gratification’, homes in historic places rather than flashy new-builds. As wealth piles up, but fewer people feel comfortable about showing off, the trend is towards what might be called (with apologies to Thorstein Veblen, who coined the term ‘conspicuous consumption’ in 1899 to characterise the competitive extravagance of the plutocracy) inconspicuous consumption.

Not every billionaire yearns to be anonymous (remember Sir Richard Branson), but many do. In a crowded, prying age, privacy is at a premium. Silence is golden. Bright stars in a velvet-dark sky astound citydwellers used to horizons with an orange glow. One exhibit in the show hints at intangibles such as these: to help redress the balance in an often over-organised world, Marcin Rusak has produced a kit that will help rediscover spontaneity. It includes a dial-less watch that heats up with the sun, a compass for discovering random places and a blanket to keep warm on the journey. When everyone has satnav, there’s a real luxury in getting lost.

‘What is Luxury?’ is at the V&A, London SW7, until September 27 (020–7942 2000; www.vam.ac.uk)

Exhibition review: Mackintosh Architecture at RIBA, London

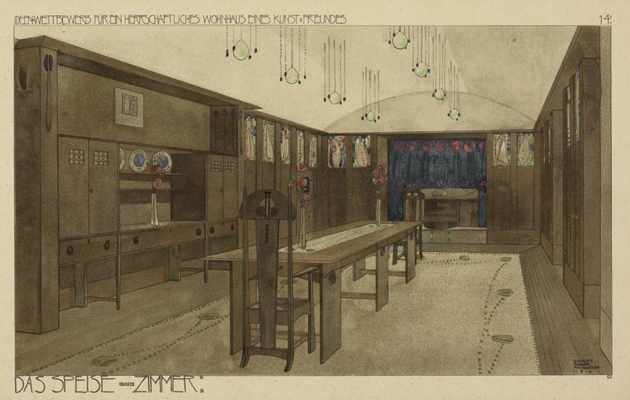

Gavin Stamp explores a show of Charles Rennie Mackintosh designs.