Henry Moore: The sculptor who achieved the impossible

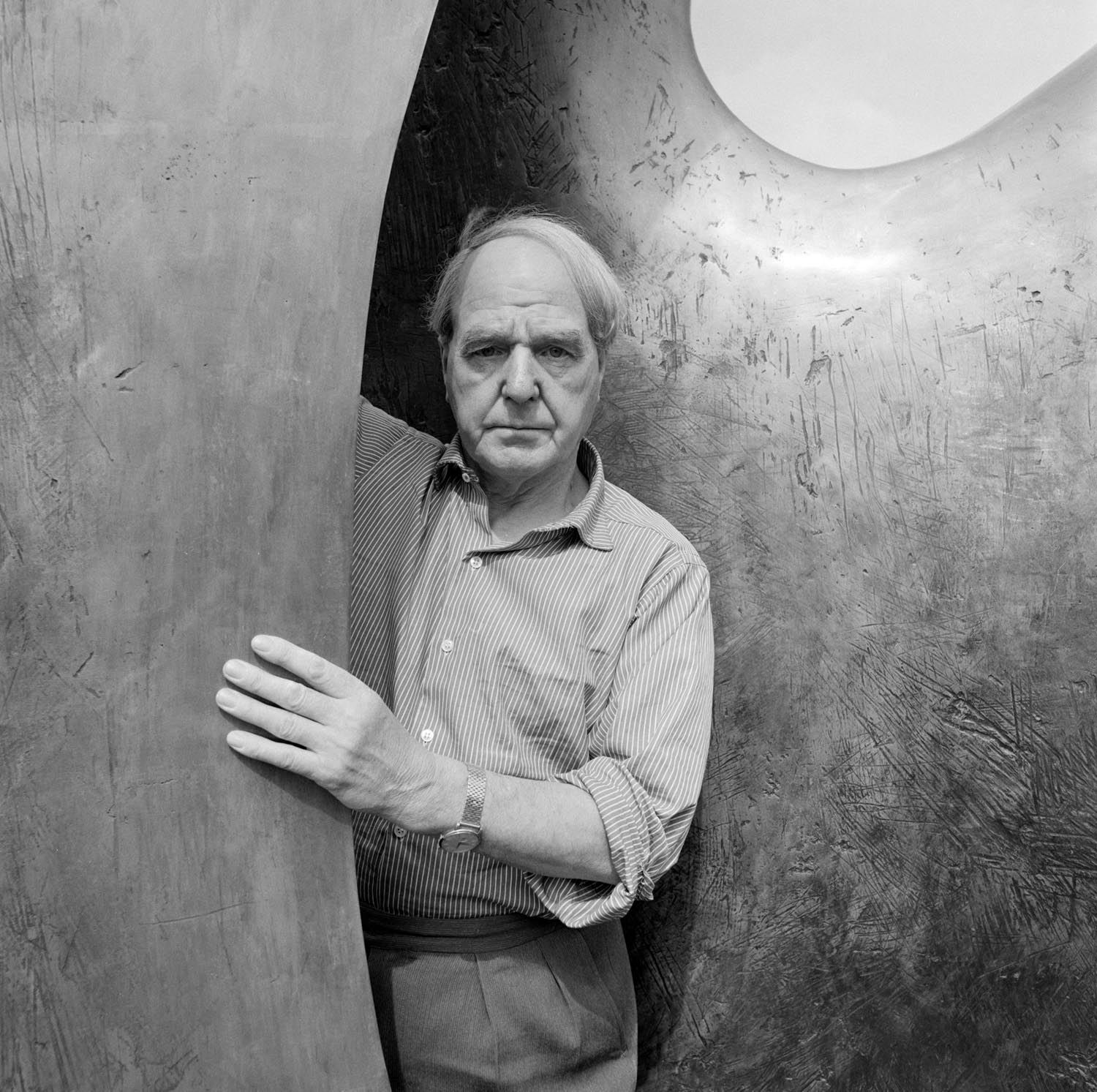

Henry Moore achieved international fame as a sculptor, despite once being denounced for promoting ‘the cult of ugliness'. And he also remained a most unassuming man, finds Laura Gascoigne, as two new exhibitions of his work prepare to welcome visitors.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Sculptors are very rarely household names, but no one who lived through the 1960s could be unfamiliar with the name of Henry Moore. At the height of his international success, Moore’s monumental public sculptures in prominent locations — from the 12ft-high Knife Edge Two Piece (1962–65) outside London’s Houses of Parliament to the 26ft-long Reclining Figure (1963–64) outside the Lincoln Centre in New York, US — became such a feature of the urban landscape that they appeared in cartoons in the popular press. For a Modernist abstract sculptor, that was fame.

Moore had come a long way in the 30 years since his exhibition at the Leicester Galleries, in 1931, was denounced by the Morning Post for promoting ‘the cult of ugliness’, sparking a furore that cost him his teaching job at the Royal College of Art. His sin, in the eyes of traditionalists, had been to abandon the classical ideal of human beauty in favour of something earthier, chunkier and more ‘primitive’. The Yorkshire lad who set his heart on becoming a sculptor after learning about Michelangelo at Sunday school had gone his own way.

Achieving that childhood ambition had not been easy. Moore’s self-educated father, who had risen from miner to under-manager of the Wheldale Colliery in Castleford, West Yorkshire, viewed sculpture as a form of manual labour with poor career prospects. He wanted Henry, the seventh of his eight children, to become a teacher, like three of his siblings. Moore, for his part, had other ideas. In 1917, after a year of teaching, he escaped the profession by enlisting in the army as the youngest soldier in the Prince of Wales’ Own Civil Service Rifles. Paradoxically, it would be army service that opened the door to his artistic career. An ex-serviceman’s grant paid for his sculpture studies at Leeds School of Art, whence he won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in 1921.

In London’s museums, Moore ‘could learn about all the sculptures that had ever been made in the world’. But it was at the Musée du Trocadéro in Paris in 1925 that he came across the cast of a Toltec-Mayan chacmool that inspired his enduring motif: the reclining figure. For an artist whose earliest memories of stone had been shaped by the medieval tombs in his local church of St Oswald, Methley and the outcrops of Adel Crag near Leeds, this recumbent Mexican rain spirit, with knees raised like hillocks, seemed to merge the human figure with the forms of the landscape.

‘Static and strong and vital, giving out something of the energy and power of great mountains’ is how Moore described the sculptures that moved him in 1930. Landscape was fundamental to his vision; organic forms, from rocks and trees to shells and pebbles, were endless sources of sculptural ideas.

After he and his wife, Irina, moved in 1940 to a farmhouse, Hoglands, in the Hertfordshire hamlet of Perry Green, following bomb damage to their Hampstead studio, Moore built up his ‘library of natural forms’, filling his maquette studio — the space where he did his thinking — with inspirational oddments: interestingly shaped flints or animal bones, driftwood and shells. The forms often entered his work quite literally, becoming physically incorporated into the clay models for his bronzes. In a new exhibition, ‘Henry Moore: The Sixties’, at Henry Moore Studios & Gardens in Hertfordshire, the 11ft-high plaster Large Spindle Piece(1968) is displayed next to the original flint that inspired it.

An early adherent of ‘direct carving’ in stone, Moore turned to casting in bronze as the scale of his work grew with his reputation. During the Second World War, however, he ‘felt it silly to make a large sculpture’ and confined himself to works on paper. His ‘Shelter Drawings’, of Londoners sleeping in the Underground during the Blitz, in huddled masses of reclining figures, earned him a commission as an Official War Artist; it took him back to his father’s old colliery to document the wartime contribution of Britain’s miners.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Oddly for an atheist, it was a commission from Walter Hussey, then vicar of St Matthew’s Church, Northampton, for a carved Madonna and Child that got Moore back into sculpting after the war. ‘Whether or not I should agree with your theology I just do not know,’ he confessed to Hussey: in his final carving, the Renaissance Madonna meets the archaic earth mother.

Moore’s pre-war sculpture had become increasingly abstract, but the war, he found, ‘directed one’s attention to life itself’; it ‘brought out and encouraged the humanist side in one’s work’. Another stimulus to figuration was the birth, in 1946, of a long-awaited daughter, Mary, when he was 47. The mother-and-child theme so central to his work was now expanded to embrace the family group.

That year marked a turning point for the artist. A retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York propelled the Yorkshireman onto the world stage; two years later, he won the International Sculpture Prize at the Venice Biennale. As his global reputation grew, the great and the good beat a path to his door. A page of his 1958 diary records visits from the Queen Mother and Somerset Maugham in the same week; other pilgrims to Perry Green included W. H. Auden, Billy Wilder and Lauren Bacall.

Even at the height of his success, Moore never moved from the modest family house surrounded by studios at Perry Green, Hertfordshire, which is now his museum. Fame and money were of no interest to him. His daughter recalls that the only celebrities he went out of his way to meet were Morecambe and Wise. The world’s most celebrated sculptor loved comedy; a committed humanist, he was profoundly human.

Roger Fry is said to have remarked that he couldn’t be a real artist because he always stopped for lunch. Mary writes in her memoir, Some Home Memories, that her father downed tools not only for lunch, but also for elevenses and 4pm tea, when the whole Perry Green team — secretary, cleaners and studio assistants — came together. However busy his schedule, at 7pm, it would be back to the studio for a final hour before joining Irina for a whisky in front of the television. What astonished Mary was her father’s ability ‘to vanish into a studio and immediately access that other intuitive, subconscious world which feeds great creative ability. And then, just as easily, quit to join my mother for that whisky in front of the box’.

Pace Fry, that ability — not skipping lunch — is the test of an artist.

‘Henry Moore: The Sixties’ is at Henry Moore Studios & Gardens, Perry Green, Hertfordshire, until October 30 — 01279 843333; www.henry-moore.org

Standing stones

In the 1950s, Moore added a new subject to his signature themes of the mother and child and the reclining figure. As a young man, his first sight of Stonehenge by moonlight, in 1921, had left an indelible impression; 30 years later, he began a series of large bronze totemic forms recalling prehistoric monoliths.

Examples of these Upright Motives, as well as related etchings and lithographs, are currently on show in the exhibition ‘Henry Moore: Sharing Form’, contrasting with a more intimate display of memorabilia selected by his daughter, Mary.

‘Henry Moore: Sharing Form’ is at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Bruton, until September 4 — 01749 814060; www.hauserwirth.com

Photo credits: Barry Warner; Alamy; Nigel Moore/Henry Moore Foundation; The Henry Moore Foundation Archive; Jonty Wilde; Ken Adlard/Hauser & Wirth/Henry Moore Foundation

Credit: Pete Huggins

Henry Moore at Houghton Hall: Where ancient architecture meets modern art

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.