Hope blooms eternal: Tom Young paints Lebanon's beauty, without shying away from the scars of conflict

'In situations where there is conflict or displacement, or trauma, art can help in some sort of healing process. When there are barriers, it can transcend them'

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For Tom Young, painting is like breathing. ‘It’s a very natural thing for me to do, it’s how I respond to the world around me,’ he says. ‘In situations where there is conflict or displacement, or trauma, art can help in some sort of healing process. When there are barriers, it can transcend them.’

Tom’s work is all about making connections, finding common ground and shining light on dark places. Art and adventure alike are in his blood: his great-great-aunt was Marianne North, the pioneering botanical artist who ‘went to just about every corner of the earth. She seemed to be able to settle anywhere,’ he says, admiringly. Her mentor was Edward Lear, who made his name painting the cedars of Lebanon. His grandmother, Dorothy Vaughan, was brought up in India and would take the young Tom out painting in oils: ‘I grew up with her stories of travel and how she used her art to connect to the local people.’

A formative experience came when he was 11 and he was taken to Palestine. ‘My mother died when I was 10 and her sister looked after me,’ he explains. ‘My aunt and uncle were, let’s say, politically edgy. I remember them having arguments with the Israeli tour guide and IDF soldiers, saying “you call this a holy land, but you don’t look very holy to me”.’ Attending a Christian school and singing hymns about those places, ‘I wondered why we knew about them and why they were important’. He also experienced Islamic ways with his father, Christopher Young, a criminal court judge who worked in London and the East Midlands. ‘After Mum died, I started to go to functions with the Islamic communities there and learn about this other culture.’

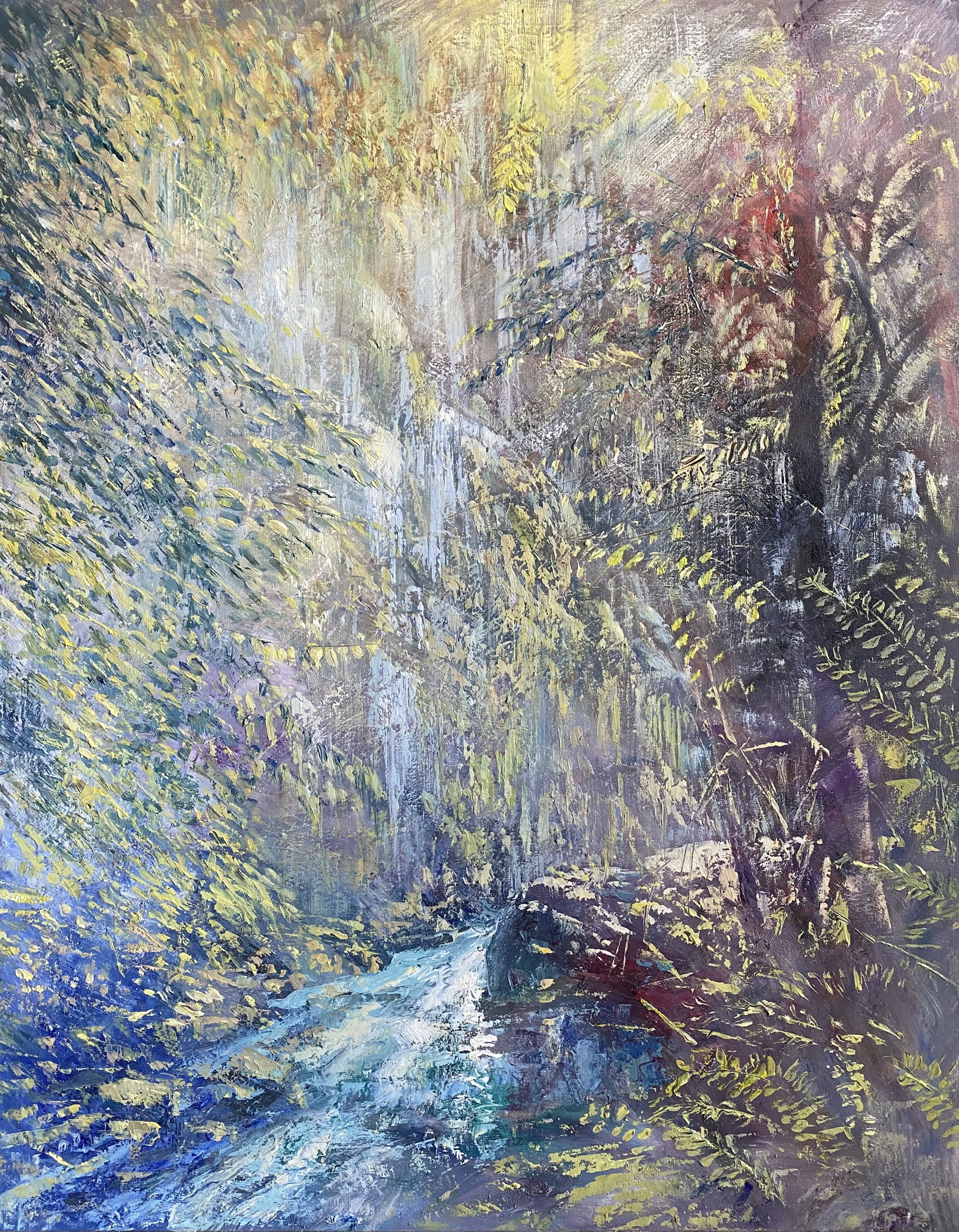

Qadisha Waterfall captures the ethereal beauty of the Qadisha Valley.

'When the blast happened, Tom was out of his then studio for the first time in months, which quite possibly saved his life. Paintings were slashed by flying glass, in strangely symbolic places'

He studied fine art at Norwich School of Art, then architecture at Newcastle and in Istanbul, before establishing a successful career as an artist grounded in the tradition of English romanticism and French Impressionism. From his base in London, he painted the sun-soaked beauty of the south of France, Spain and Italy, but began to feel that ‘I was capable of more, that these places were perhaps a bit pedestrian, a bit safe’.

Then came 9/11 and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. ‘That was the moment that I became engaged and angry,’ he remembers. ‘I love the British and how kind and friendly we are, but I didn’t see that reflected in our policies, sadly. It infuriated me, so I was looking for a way to engage with these issues in my work.’

He was then living in London’s Notting Hill, where his car mechanic Raed Zahreddine had a garage next to Lucian Freud’s — who himself had admired Tom’s work and is an inspiration, as are Eric Ravilious and Edward Bawden. The mechanic, homesick for Lebanon, saw his paintings in his car and commissioned him to go there. ‘I knew of the country through the news, but I was also aware that Beirut was a place of beauty and glamour.’ He went in spring 2006 and found something strange. ‘It felt as if I’d come back home, like I’d been there before. I could read the lie of the land.’

Asphixiated City (Angelus Novus), a view of Beirut from the sea painted during last year’s conflict.

After travelling around Lebanon and Syria, Tom earned a commission from a Lebanese man who had been to Stowe School in Buckinghamshire and had a collection of classic cars. ‘I said I’d do it if I could get behind the wheel of his E-type!’ He responded to the blend of East and West, Christian and Muslim: ‘I just loved the place. People were happy to see a foreigner who wasn’t fishing for trouble, someone who appreciated their home. It is so friendly, people would bring me tea and cakes when I was painting on the streets and tell me stories and invite me for coffee.’

There is a strong artistic tradition in this tiny country at the eastern end of the Mediterranean and Tom cites the lyrical painter Omar Onsi (1901–69) as a favourite, as well as the contemporary artists Ayman Baalbaki and Daniele Genadry. Amid the galleries, festivals and exhibitions, Tom found a ready market for his work. ‘It’s really buzzing. Lebanon has an exciting energy, sophisticated and liberal, it’s always been a haven for creative freedom, being surrounded by less liberal countries.’

Soon after he returned from his first visit, the Israelis attacked. ‘Lebanon had been getting back on its feet after the civil war and I had a lot of friends in the firing line. I decided I had to go back to show solidarity.’ He acted on his impulse and began painting with children in the bombed areas, eventually collaborating with the Lebanese community in London to arrange an exhibition of their work and his. ‘We had a guest musician at the opening, a then unknown British-Lebanese singer called Mika’ — he is now a Grammy award-winning artist.

A post shared by Tom Young (@tomyoungart)

A photo posted by on

Wondering if it was wise to become too connected with a country that had experienced so much trauma, Tom took on a commission to paint in India. ‘It was an amazing time, but I never forgot about Lebanon.’ Back in London, Indian art dealer Indar Pasricha saw the show, but was more captivated by his Lebanese work and gave him an exhibition, the first time he’d shown anything other than Indian art. ‘I went all the way to India to get away from Lebanon and got sent straight back!’

The 2008 crash caused a lull in the London art market, so when a Beirut gallery asked him to do a solo show, it was an easy decision. Now, he is engaged to a Lebanese woman and has an enchanting studio in Gemmayzeh in northern Beirut. His paintings draw on his architectural training, with complex street-scapes that reward long and close looking.

In some, giant flowers rise from the rubble, symbolising new life after conflict and decay; in others, past and present or even cities merge together: Beirut becomes London in an intricate web of roofs and streets linked by Tower Bridge. Grand old houses from when Beirut was known as the Paris of the Middle East, the ancient Mediterranean towns of Tripoli and Saida, lines of refugees in Gaza, glittering rivers and sunsets over the Bekaa Valley vineyards: complex and powerful, each one tells a story of war or beauty, loss or hope.

A few minutes’ walk from his home is the port of Beirut, horribly familiar from the catastrophic explosion of 2020. When the blast happened, Tom was out of his then studio for the first time in months, which quite possibly saved his life. Paintings were slashed by flying glass, in strangely symbolic places. Another uncanny effect occurred with the huge Asphixiated City (Angelus Novus), a view of Beirut from the sea painted during last year’s conflict. An accidental splash of white paint became an angelic figure, its upstretched hand touched by an undirected dribble of liquid black from the ravaged sky.

Woman of the South: 'We are told that a woman in a hijab is oppressed and powerless… that might be true, but the image of this woman, confronting military might, was so powerful. “This is my land, you cannot take it.”'

‘I’m still rooted here, in the English countryside, and I wanted to show the connections and challenge the stereotypes. People don’t see [the beauty of Lebanon] in the media. They get one story and that’s it, they don’t see the complexity.’

One of his most powerful paintings tells of a Tiananmen Square moment. Early this year, when Israeli tanks rolled into southern Lebanon, a hijab-clad woman faced them down. ‘It was disruptive of so many stereotypes. We are told that a woman in a hijab is oppressed and powerless… that might be true, but the image of this woman, confronting military might, was so powerful. “This is my land, you cannot take it.” She was shot and bleeding, surrounded by soldiers, yet they backed off, because she wasn’t afraid.’ Tom appeared on Lebanese television discussing the painting and Zahraa Qobeisy recognised herself. She contacted him and he invited her to his permanent exhibition in Saida, now a thriving cultural centre. ‘It’s very near the southern border, so it seemed appropriate to exhibit there and show solidarity.’

The courageous Lebanese and their landscapes, especially the deep Qadisha Valley, Mount Lebanon, with its high waterfalls and ancient monasteries, create a ‘traffic jam’ of ideas in Tom’s head. He paints en plein air before working things up in his studio: ‘It’s important to absorb the atmosphere, the light, to listen to the birds and the wind and the waterfalls.’ His current exhibition is deliberately uplifting, with British landscapes alongside Lebanese, painted in his chosen oils, often with a palette knife. ‘I’m still rooted here, in the English countryside, and I wanted to show the connections and challenge the stereotypes. People don’t see [the beauty of Lebanon] in the media. They get one story and that’s it, they don’t see the complexity.’

His works are as complex as our messy world. Therein lies their power.

‘Flow States’ is at Marie Jose Gallery, No 16, Victoria Grove, London W8, until July 26

This article originally appeared in the July 16 issue of Country Life.

Octavia, Country Life's Chief Sub Editor, began her career aged six when she corrected the grammar on a fish-and-chip sign at a country fair. With a degree in History of Art and English from St Andrews University, she ventured to London with trepidation, but swiftly found her spiritual home at Country Life. She ran away to San Francisco in California in 2013, but returned in 2018 and has settled in West Sussex with her miniature poodle Tiffin. Octavia also writes for The Field and Horse & Hound and is never happier than on a horse behind hounds.