In Focus: A show that uses Degas, Picasso and Cezanne to warn us about the post-Brexit world

A pre-lockdown trip to ‘Degas to Picasso: International Modern Masters’ at the Pallant House Gallery leaves you feeling that British Modernism isn’t easy to pigeonhole — not now, and not a century ago. That's the feeling of Charles Darwent after viewing a show that epitomises an international movement.

This winter’s show at Pallant House Gallery is both much as you’d expect from its name — and rather less so. Expected, because it includes works by the usual suspects of International Modernism — Matisse, Picasso, Paul Klee and so on — and unexpected, because of where it is.

Pallant House is best known as a mainstay of that sort of art called ‘Modern British’. A hassock’s throw from Chichester Cathedral and in a handsome Queen Anne house, the gallery certainly looks the part: it comes as little surprise to find that its founding collection was given by a Church of England cleric, Walter Hussey. Yet the new show — currently closed due to lockdown, but which should run well into April when things reopen — is drawn from Pallant House’s own collection, which does come as faintly surprising.

That it should is telling, however. Rather as the 20-year-old division of Tate into galleries called British and Modern suggests, inconveniently, that art cannot be both, so Modern British art has, for a century, defined itself as national rather than international. How, Paul Nash asked, in 1932, was it possible to ‘go modern and be British’? It is a question that resonates as you walk through this show.

What quickly becomes clear is that internationalism was at the very heart of the International Modern project. Go around the show backwards and you will find, on the first wall to your left, two works on paper made in 1957, in a style now known as Abstract Expressionist. The nearer, Green with Blue and Red, is by the Chicago-born artist, Norman Bluhm. Next to it is Composition by Sam Francis, a Californian.

Abstract Expressionism is, famously, an American invention, the brainchild of artists such as Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko, both in the New York School. And yet these two works were made by painters whose formative years had been spent not in Manhattan, but Paris. Additionally, the freehand dripping of Francis and Bluhm owes its looseness to a style of automatic painting brought to America in the 1940s by Parisian Surrealists fleeing German occupation. What we’re seeing, in other words, is an American art invented by Frenchmen and reimported to France.

To add to the confusion, Parisian friends of Bluhm and Francis, such as Jean-Paul Riopelle and Pierre Soulages, eagerly took up the new (and highly successful) ‘American’ style: Soulages’s monolithic black forms, hung further along on the wall, might easily have been painted in New York. Muddying the waters still further, neither of the founding fathers of Abstract Expressionism mentioned above was actually born in America, de Kooning being Dutch and Rothko Ukrainian.

It goes on. Josef Albers’s two ‘Variants’ — dating from 1966, they are among the most recent works in the exhibition — were made at Yale, where Albers was then teaching, but the rationalist roots of their geometry lie in an earlier job, at the Bauhaus in Albers’s native Germany.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

"Pallant House is, perhaps, issuing a gentle warning: it is possible to be British and go modern, but that it isn’t necessarily easy"

Diagonally across from these are a suite of prints made by the Belgian Pierre Alechinsky, working in a Parisian print shop set up by an Englishman, Bill Hayter. Called Hayterophiles, they are an unspoken hint of something missing from this show: the thing for which Pallant House is best known — Modern British art.

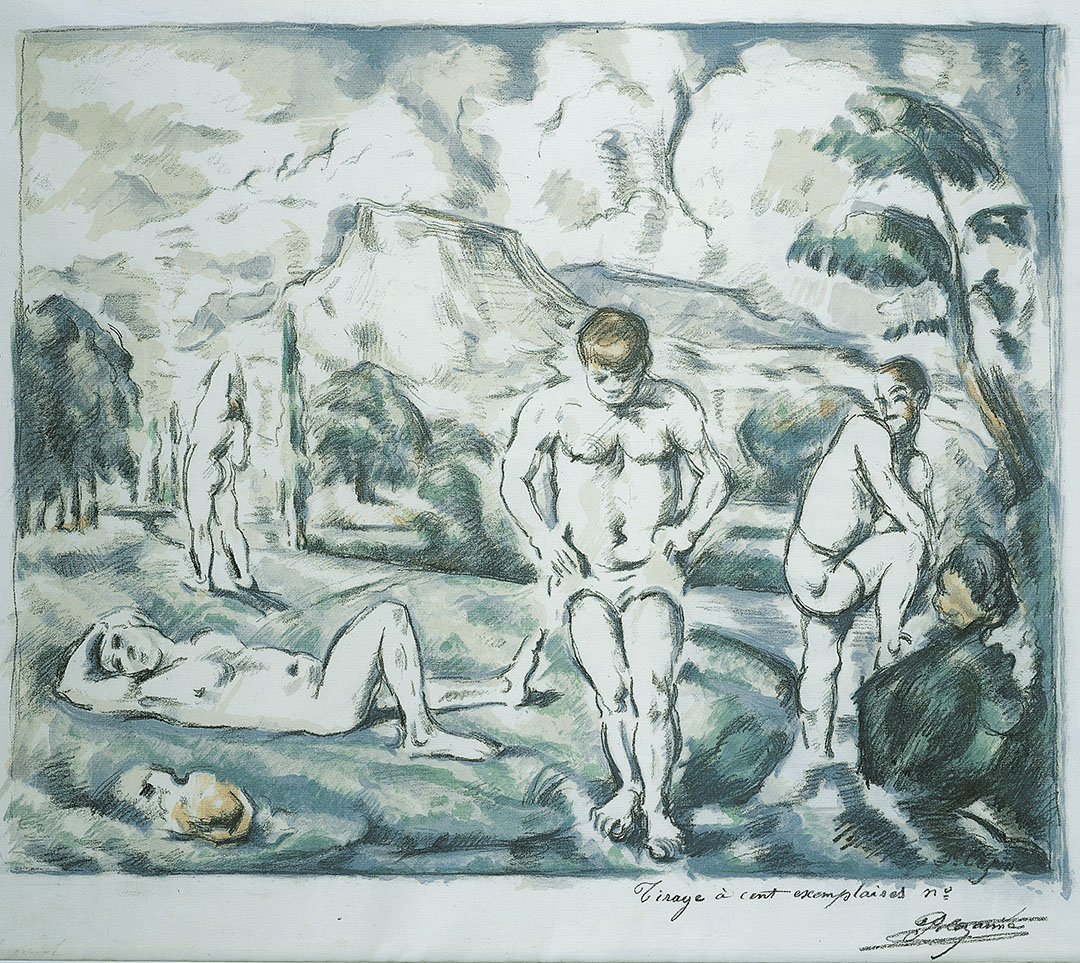

The only other nudge is in the exhibition’s first (or, by my reverse navigation, last) room, which takes us to the roots of Modernism under the beady eye of its founder, Paul Cézanne. Here, behind the back of a self-portrait by Cézanne, are two works by Walter Sickert. As in George Cukor’s The Women (1939), it is the shadow of a bellboy that alerts us to the film having no male actors, so does Sickert’s Jack Ashore (1912–13) remind us of the lack of British works in this show.

Why is this painting included? Perhaps because it is so clearly influenced by Degas’s brothel paintings of the 1870s. Or perhaps to remind us that Sickert, that most British of painters, was born in Germany of a Danish father and spent much of his career in Dieppe.

At the time when the UK has finally left the EU, Pallant House is, perhaps, issuing a gentle warning: that, pace Nash, it is possible to be British and go modern, but that it isn’t necessarily easy.

‘Degas to Picasso: International Modern Masters’ is currently closed due to coronavirus restrictions, but when things reopen will run at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, West Sussex, until April 18, 2021 www.pallant.org.uk

Toby Keel is Country Life's Digital Director, and has been running the website and social media channels since 2016. A former sports journalist, he writes about property, cars, lifestyle, travel, nature.