In Focus: How David Hockney chronicled the first spring of Covid-19 with iPad art

Ahead of David Hockney’s forthcoming exhibition at the Royal Academy, Martin Gayford considers the octogenarian’s fresh and lyrical iPad evocations of spring in the French countryside.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Last year, when chatting on FaceTime, David Hockney happened to mention the late Ahmet Ertegun, the founder of Atlantic Records and an old friend of his. Ertegun, Mr Hockney remarked, ‘was a very funny man’. ‘When someone asked him “where do you live normally?”, he answered: “I don’t live normally!”’

The same is true of the painter himself. He has not only led a most extraordinary life, but he’s still leading it right now in his mid eighties with flat-out energy and full creative power. If anything, Mr Hockney seems to become more prolific with age. On May 23 (all being well), a remarkable exhibition, ‘The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020’, will open at the Royal Academy (RA). It consists of the work he did last year during that beautiful spring, which was also the season when Covid-19 began to change our lives.

I visited Mr Hockney the summer before in 2019, a few months after he’d moved into his new house and studio in a rustic corner of north-west France. We talked all afternoon and into the night, sitting beside the lily pond as the frogs croaked and the moon rose above us. I’d expected to return last year. However, of course, like everyone else, he and I abruptly found ourselves locked down.

After a while, we got into a pattern of chatting at a distance, via FaceTime. And, bit by bit, what we said and thought grew into a book, Spring Cannot be Cancelled, which is published this month. It is full of reflections on art and passing time, anecdotes, memories and also a sort of portrait in words — many of them Mr Hockney’s — of a remarkable artist flourishing during an exceptional time.

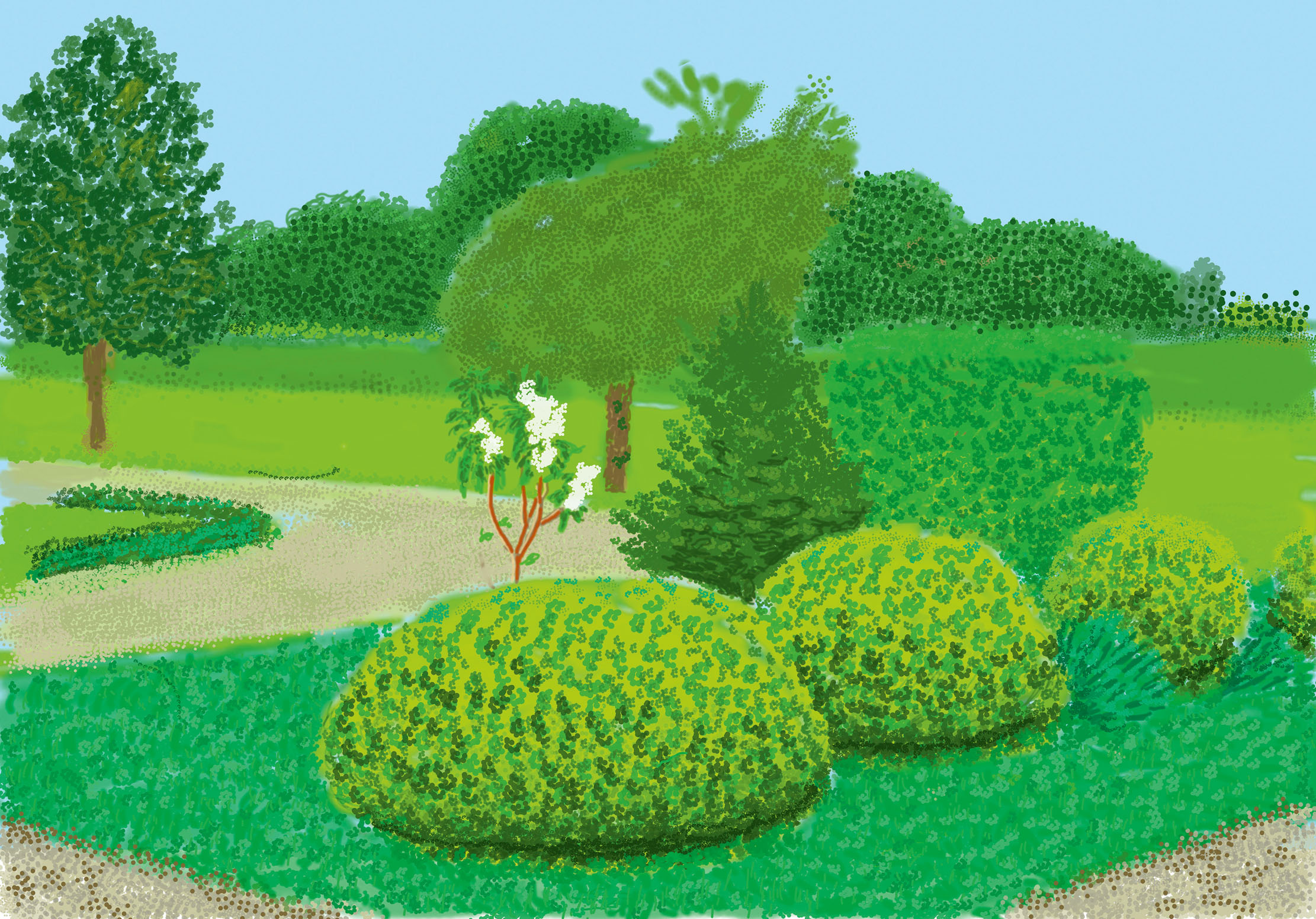

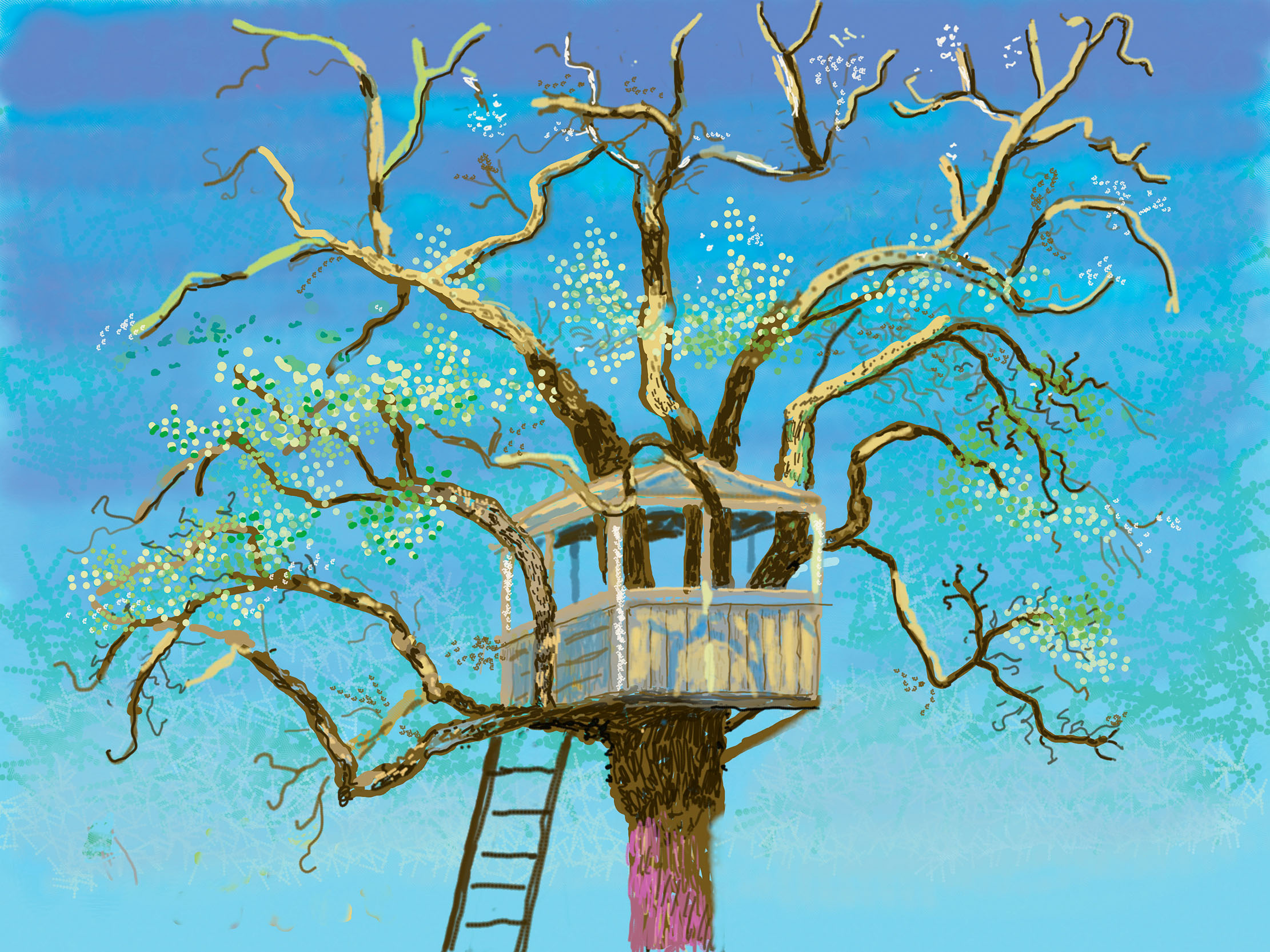

Between early March 2020 and the beginning of summer, he produced more than 100 new works on his iPad: fresh, lyrical and often ravishingly beautiful. There are spectacular sunsets, fruit trees in blossom, delicate dawns, shadowy moonlight, water rippling under raindrops. Every one of these sights was seen in and around the old, wood-beamed French farmhouse where he now lives. ‘I can’t stop actually,’ he confessed at the time. ‘Everywhere I look, there’s something!’

It isn’t so much that for Mr Hockney ‘less is more’ — although his subject matter is restricted to a few trees, a little brook and meadow — as that more is more. The more he looks at his surroundings, the more he sees. Certain aspects — such as the cherry tree, the dying pears with bare branches at their tops, which look, he thinks, like a ‘clapping hand’ and the little lily pond — recur again and again in different lights, at various times of day and points in the annual cycle of growth.

There is nothing particularly unusual about any of them; they are objects that you might find almost anywhere in the Northern European countryside. In a way, that is the point. It’s not what you look at that makes a subject interesting, it’s how intensely you look at it and how much you think and feel about it.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Mr Hockney likes to tell a story about Sister Wendy Beckett, the art critic and nun. Once, seated next to him at a dinner party, she posed a question: ‘She asked: “Was I a Constable man or a Turner man?” I answered: “What’s the difference?” At this, Sister Wendy explained: “Well, Turner loved spectacular effects, but Constable painted what he loved.”’ To which Mr Hockney smartly objected: ‘But Turner loved spectacular effects!’

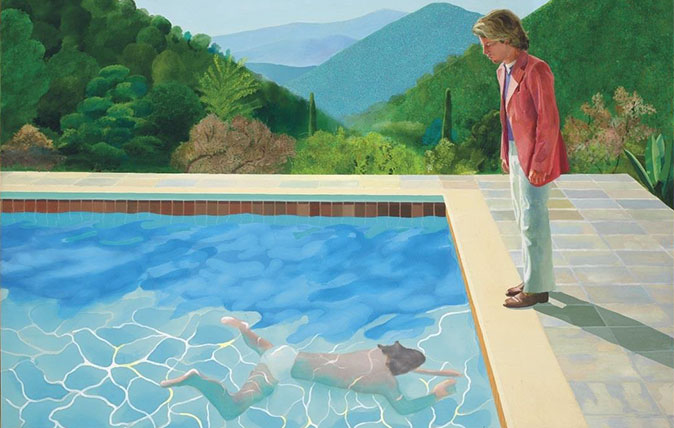

Of course, Mr Hockney loves them, too (as is shown by those marvellous sunsets and dawns from last year’s crop of pictures). And, in some respects, his career has resembled Turner’s. As was his great predecessor, he was a youthful prodigy, achieving fame when he was still at the Royal College of Art in the early 1960s. The world of art is more subject than most to fluctuations of fashion; nonetheless, he has been continuously in the spotlight ever since: always famous, always doing something fresh.

Since his Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), of 1972, went under the hammer for $90 million at Christie’s New York in 2018, Mr Hockney has held the title of the world’s most expensive living artist at auction. It was an accolade of a sort, but Mr Hockney’s only response was to echo Oscar Wilde: ‘The only person who likes all kinds of art is an auctioneer.’

Also echoing Turner, Mr Hockney has led a wandering life. In the popular mind, he is most associated with two places: Yorkshire and California. He was born and brought up in Bradford and returned to the county in the 21st century to settle in the Yorkshire Wolds, near Bridlington.

In one crucial respect, however, he is emphatically in the Constable camp. As the 19th-century landscape painter found subjects for masterpiece after masterpiece within a few hundred yards of towpath along the River Stour, so Mr Hockney has in the environs of his Norman house. The surrounding trees became old friends to him, as did the ‘higgledy-piggledy’ beams of the building (the artist and his assistant Jean-Pierre Gonçalves De Lima, or ‘J-P’, delight in that word).

‘You should paint what you love,’ Mr Hockney reflects. ‘I’m painting what I love now — I’ve always done it.’ It’s true. Many of his works depict a small number of people close to him: friends, family, partners, his mother. He’s made many pictures of his dogs and the ordinary things around him: vases of flowers on his bedroom window, even ashtrays and the kitchen sink.

Mr Hockney has long been searching for the perfect place to work, rich in inspiration, free of interruptions — which, from time to time, temporarily at least, he has found before. His Norman farm is only his latest retreat, although perhaps the most satisfactory. He has had a lifelong urge to escape from ‘boring old England’ where ‘you can’t do this, you can’t do that!’ It was partly that impulse that took him to the US half a century ago.

For decades, he has also been in flight from the consequences of his own fame and sociability. He found a refuge in Paris in the 1970s, but, before long, found himself plagued by visitors. ‘They’d arrive at 3pm and stay until midnight.’ In the end, it got so bad he ‘just packed up and went back to London’.

As did his hero Picasso, Mr Hockney restlessly explores new artistic tools and idioms in which to depict the world around him. One of his slogans is: ‘There’s always another way to do it!’ Thus, in the 1960s, he moved in a few years from near abstraction to a highly naturalistic style. In the 1970s, he changed direction, beginning to investigate the ways in which space was depicted in Picasso’s Cubism. Simultaneously, he pioneered new media, some of his own invention, including photo-collage and prints made with fax and photocopier. Nor did he stop there; as technology moved forward, so did Mr Hockney.

In Yorkshire, in the early 21st century, he worked in time-honoured media, such as watercolour, oil paint and charcoal, but he also devised a groundbreaking idiom of multi-screen film. Soon after the iPhone was launched, he got one and taught himself to draw on it. When the iPad arrived, he moved onto that; last year, he returned to that device (albeit using an updated drawing programme devised especially for him).

The first group of Normandy works from 2019 were created with paints, brush and a reed-pen — similar to the ones that Rembrandt and van Gogh (two other heroes) — employed. However, in March 2020, Mr Hockney was poised, iPad and stylus at the ready, to begin his Arrival of Spring.

Part of the appeal of the iPad as a medium is its ease of use. It’s always there, always ready. When, last April, he saw a so-called ‘supermoon’ through scudding clouds, he instantly made a drawing. ‘I’d got up for a pee and saw it through the window. I drew it quickly on the iPad. If I’d had to use brushes and paints, it would have taken much longer and I would have lost the impact it had on me.’

I remember him pointing out that van Gogh wouldn’t have got so far so fast in Arles if he hadn’t been isolated. Clearly, Mr Hockney felt the same was true of him in Yorkshire, but even more in Normandy. One great advantage of the latter is that he’s living amid his subject: ‘That makes an enormous difference because I get to know the trees a lot better!’

Mr Hockney enjoys talk and company, yet he is also utterly committed to work. Once he made an offhand remark, which could stand as a concise, one-sentence autobiography: ‘I’ve always been a worker.’ The Hollywood Hills and Bridlington both offered a sanctuary from interruption, but rural Normandy, especially in lockdown, proved to be perfect.

‘At night,’ he told me happily, ‘I’d go to bed planning what I was going to do next. I always had it in my head. I’m not sure I’d have been able to do those drawings so rapidly if I’d had more visitors.’ In his first London flat, he put a notice in large capital letters on the chest of drawers reading ‘GET UP AND WORK IMMEDIATELY!’ Evidently, he hasn’t changed.

In the past, Mr Hockney has had a romantic urge to roam the world. These days, he’s content to stroll from his house to his studio and down to the little river at the bottom of the meadow. ‘This place is perfect for me right now,’ he often reflects. ‘I think I’ll just stay here.’ Many art lovers, seeing the work he is producing there, will very much hope he does.

‘Spring Cannot Be Cancelled: David Hockney in Normandy’ by David Hockney and Martin Gayford, ‘an uplifting manifesto that affirms art’s capacity to divert and inspire’, is out now (£25; Thames & Hudson). ‘David Hockney: The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020’, is at the Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, London W1, May 23–September 26 (020–7300 8090; www.royalacademy.org.uk)

In Focus: The war artist who taught Hockney, and whose reputation is only going to grow

In Focus: The David Hockney Grand Canyon image at the end of a years-long mission to 'photograph the unphotographable'

David Hockney's mission to create art that captures the natural wonder that is the Grand Canyon takes centre stage at

Credit: Via Christie's

In Focus: Hockney, Banksy and the battle of 'fine art' vs 'a stencilled publicity stunt'

David Hockney's evocative 1972 masterpiece Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) set a record for a living artist

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.