In Focus: The Anglo-German pacifist-turned-war artist who famously chronicled Dunkirk — despite not being there

Richard Eurich was a war artist, draughtsman and visionary painter of people, landscape and the sea. In this 80th anniversary year of the retreat from Dunkirk, and with a new book and exhibition celebrating his career, Peyton Skipwith considers his work.

On August 15, a service was held at the National Memorial Arboretum to commemorate the 75th anniversary of VJ Day. Several other notable Second World War anniversaries have occurred in the past few months: August 19 was the 78th anniversary of the disastrous landing at Dieppe; two months earlier, services of thanksgiving, muted due to lockdown, marked the 80th anniversary of the evacuation of Dunkirk.

This remarkable feat took place over eight days, between May 26 and June 4, 1940, when 338,226 British, Belgian and French troops, abandoning everything — tanks, vehicles and equipment — were evacuated from mainland Europe in a flotilla of some 800 little ships of all descriptions. It inspired Churchill’s ‘We will fight them on the beaches’ speech and entered into folklore. For many, it will come as a surprise to realise that the most popular image of this event, Withdrawal from Dunkirk, June 1940, was painted by a Quaker pacifist artist of Anglo-German descent, who wasn’t even present.

Richard Ernst Eurich was born in Bradford, Yorkshire, the son of a distinguished bacteriologist, himself a second or third generation Bradfordian. A cultured city with two theatres, two music halls, its own orchestra and an art gallery, Bradford was the heart of the international wool trade, attracting merchants from across the world, especially Germany. J. B. Priestley described the city as ‘grim but not mean’ and Eurich later recalled that ‘it was the look of Bradford that made me want to paint. The mills and steep streets were so beautiful’. As a somewhat solitary child, Eurich loved observing this world from an upstairs window, appreciating the fact that he had a grandstand view of all that went on in the streets below.

As a teenager, his precocity gained him an introduction to the Horton-Fawkes family, descendants of Turner’s patron Walter Fawkes, and he used to bicycle north to their home, Farnley Hall, to look at their collection of the master’s work. Eurich recorded some years later that ‘Turner has always been my very own particular god’.

Another early influence was the impact made on him by the 1916 exhibition at the City Art Gallery, Cartwright Hall, of work by the avant-garde Yugoslav sculptor Ivan Mestrovic. Eurich attended Bradford College of Arts and Crafts from 1920 to 1924, before winning an exhibition to the Slade. By this time, he had added Cézanne to his pantheon of heroes, provoking Prof Tonks to comment in one of his reports: ‘This student is being influenced by painters who have not been dead long enough to be respectable.’

In London, he met Sir Edward Marsh, Sir Winston Churchill’s private secretary and a generous patron of young artists. Apart from purchasing pictures, Marsh introduced him to the work of Christopher Wood, whose influence is clearly evident in Eurich’s 1932 self-portrait, Green Shirt, with its uncompromisingly direct vision and bold brushstrokes, as well as in the simplified handling of its maritime background.

The sea was to play an important role in Eurich’s art from the first moment he set eyes on it during a family holiday at Whitby in 1911. He later described it as ‘a symbol of a certain loneliness which I have always desired and the sight of the sea has always brought that constriction of the throat caused by something of almost indescribable beauty’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Memory, combined with imagination, was to provide the focus of some of his most ambitious subject paintings, such as Queen of the Sea, 1911, a fantasy recollection of that first summer holiday. A later holiday, at Bridport in Dorset in 1930, introduced him to the English Channel and, on that and subsequent visits, he painted such works as Lyme Regis and The Golden Cap, which were included in his exhibition of 1933, ‘Paintings of Dorset Seaports’, at the Redfern Gallery in London.

The following year, the sale of Blue Barge, Weymouth to the Contemporary Art Society enabled him to get married to his teacher fiancée, Mavis Pope, whose parents gave them a plot of land at Dibden Purlieu, Hampshire. Mavis’s architect brother designed their house, but, without a studio, Eurich, one of the most modest of men, worked in the garden shed until 1950. Their new home gave them easy access to both Southampton Water and the New Forest and the former became the source of an almost endless supply of motifs for drawings and paintings during the ensuing decades.

In May 1939, with extraordinary percipience, Eurich, who had never previously been abroad, booked himself a berth as the sole passenger aboard a cargo boat, the S.S. Harrogate, sailing from Hull for a trip along the North European coast from Antwerp to Dunkirk. He recorded the departure from the latter port, describing the ‘terrific long sea walls with lighthouses, and a marvellous sight looking back at the town, and then the dunes and the open sea’.

As a Quaker and pacifist, with the outbreak of war, Eurich worked on a farm and later as an ARP warden. However, feeling he could serve his country better through his art, he approached the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC) and was sent to Yorkshire, where, in 1940, he painted the eerily peaceful scene Whitby in War Time. The fee for this and its companion piece, Robin Hood’s Bay in Wartime, was £50 the pair, although the committee was so pleased with them that they gave him an extra £10.

The following June, convinced that the withdrawal from Dunkirk was the subject for which his life and training had uniquely prepared him, he wrote again to E. M. O’Rourke Dickey of the WAAC: ‘Now that the subject I have been waiting for has taken place. The Dunkirk episode. This surely should be painted and I am wondering if I should be considered for the job! It seems to me that the traditional sea painting of Van der Velde and Turner should be carried on to enrich and record our heritage.’

Dickey encouraged him to go ahead, regardless of any commission, and he worked fast, largely from imagination, assisted by the few available photographs and taking full advantage of his pre-war reconnaissance of the terrain. In early August, he took the finished painting, Withdrawal from Dunkirk, June 1940, to London for inclusion in the War Artists exhibition at the National Gallery, where it was universally acclaimed, eclipsing a work by the Official War Artist Charles Cundall, who had actually witnessed the scene. The Royal Navy reproduced it as its official Christmas card and it was later shown in the exhibition ‘Britain at War’ at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

As a direct result of the success of this and a second work, Dunkirk Beaches, May 1940, purchased for the National Gallery of Canada, Eurich was promoted to join the select band of full-time Official War Artists, with the honorary rank of captain, and seconded to the Royal Marines at Portsmouth.

The last time I saw him was at the private view of the Imperial War Museum’s sensational exhibition ‘Richard Eurich: from Dunkirk to D-Day’ (September 26, 1991–January 12, 1992). His love of Turner was very evident and, as I noted in the obituary I wrote for the Independent (June 10, 1992), ‘one wall alone contained The Raid on Vaagso, Norway, The Landing at Dieppe and Bombardment of the Coast near Trapani, Italy, each of which revealed his admiration for the 19th-century master, and each of which was a masterpiece in its own right’.

Nicholas Usherwood, in his introduction to the catalogue, noted with reference to The Landing at Dieppe that ‘Eurich was actually present in the Combined Operations Headquarters during the raid and must have been very conscious of the disaster as it unfolded’. The challenge of the war stretched him in a way he had not been stretched before and was never to be again: he worked with a speed and intensity that was breathtaking, on a scale that made the resulting works truly dramatic.

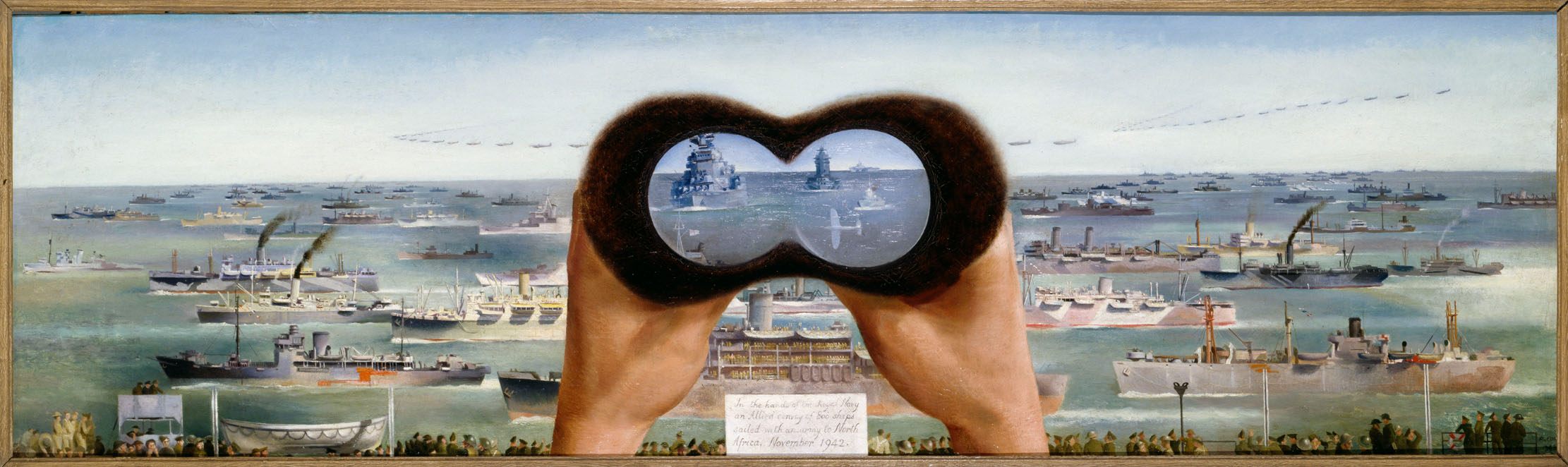

One of the most ingenious of these was his panoramic The Great Convoy to North Africa, 1942, measuring 14½in by 50in, with its wide-angle-screen effect depicting the distant ships steaming from right to left, interrupted by a pair of hands — (Eurich’s own?) — holding bridge glasses focused with frozen clarity on the central motif.

After the war, Eurich went on to paint many ambitious subject pictures, calling on his unique combination of memory and fantasy — Marine Harvest (1949), The Mummers and Gay Lane (both 1952), Queen of the Sea, 1911 (1954, his Diploma Work for the Royal Academy), Men of Straw (1957) and Mischief Night (1975) — but none is more strange than The Pleasures of Travel 1951, commissioned by Evelyn Waugh as a companion piece to two satirical works that he already owned — The Pleasures of Travel 1751 and The Pleasures of Travel 1851 — by the Victorian artist Robert Musgrave Joy. The former depicts a stage coach being held up by highwaymen; the latter passengers in a crowded railway carriage being told their journey was seriously delayed. Eurich’s take was air travellers panicking as one of the aeroplane’s engines catches fire.

The main delights from the final decades of his life, however, are the quantities of inti-mate little oils, sometimes painted on pieces of driftwood. Many depict figures on the beach, often observed in slightly surreal juxtapositions with passing ships or aeroplanes. Others capture the solitude of a colourless winter’s day — grey sky, grey sea and a flight of grey birds — or the exact opposite, scudding clouds and surf and breaking rollers. Both in his major and his lesser works, Eurich has the disconcerting gift of making the viewer aware that almost invariably there is more going on than meets the eye.

‘The Art of Richard Eurich’ by Andrew Lambirth is published in September 2020 by Lund Humphries (£40). To celebrate its launch, a small exhibition, ‘Works from the Estate of Richard Eurich’, will be at Waterhouse & Dodd, 16, Savile Row, London W1, September 21–October 3 — www.waterhousedodd.com

In Focus: The war artist who taught Hockney, and whose reputation is only going to grow