In Focus: The artist and printmaker who was 'master of the unassuming sublime'

Mary Miers considers the contribution made to British art by William Nicholson (1872–1949).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Best known in his day as a pioneering printmaker and society portraitist, Sir William Nicholson ploughed an independent furrow through the artistic fields of the earlier 20th century, conforming neither to academic convention nor the methods and interests of the Continental avant-garde.

A representational artist, he was interested in the nature of painting and was happiest doing landscapes and still lifes, in which he explored the effects of light and shadow with supreme virtuosity.

Brought up in Newark, in Nottinghamshire (his father ran the family ironworks), Nicholson studied at Hubert von Herkomer’s art school in Bushey from 1888 until 1891, when he briefly attended the Académie Julian in Paris. His paintings of the early 1890s have echoes of Clausen’s rustic plein-air studies and show his admiration for Whistler and the Glasgow Boys.

In 1893, he eloped with fellow art student Mabel Pryde; their son Ben — who would go on to become a more famous painter than his father — was born in 1894. That year, Nicholson and his brother-in-law, James Pryde, who came to live with them at Denham, founded the printing partnership J. & W. Beggarstaff, named after a ‘hearty old English name’ they’d spied on a sack of fodder.

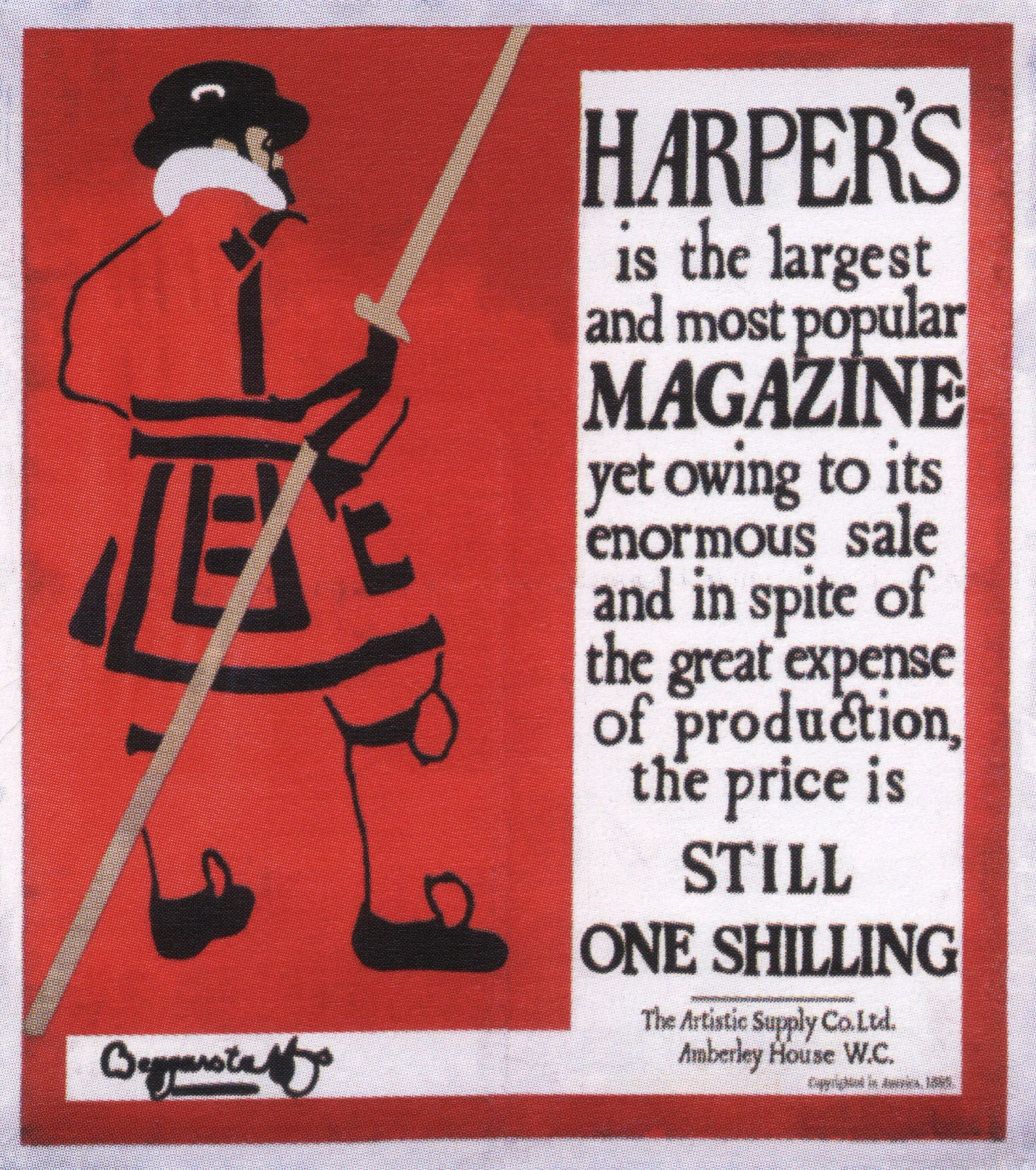

Turning to advertising as more lucrative than painting, Beggarstaffs used collage and stencil to produce striking, simplified images with bold lettering that revolutionised poster design, notable examples being for productions of Hamlet (1894) and Don Quixote (1895). Toulouse-Lautrec’s lithographic posters and the graphic work of Les Nabis, especially Bonnard and Vuillard, were clearly influential, as were images associated with English folk art and crafts, which recur in Nicholson’s earlier works.

The graphic arts were producing some of the most inventive work in Britain at this time and Beggarstaffs attracted European fame. However, the partnership ended in 1899 and the two artists became estranged, only to be reconciled in 1930.

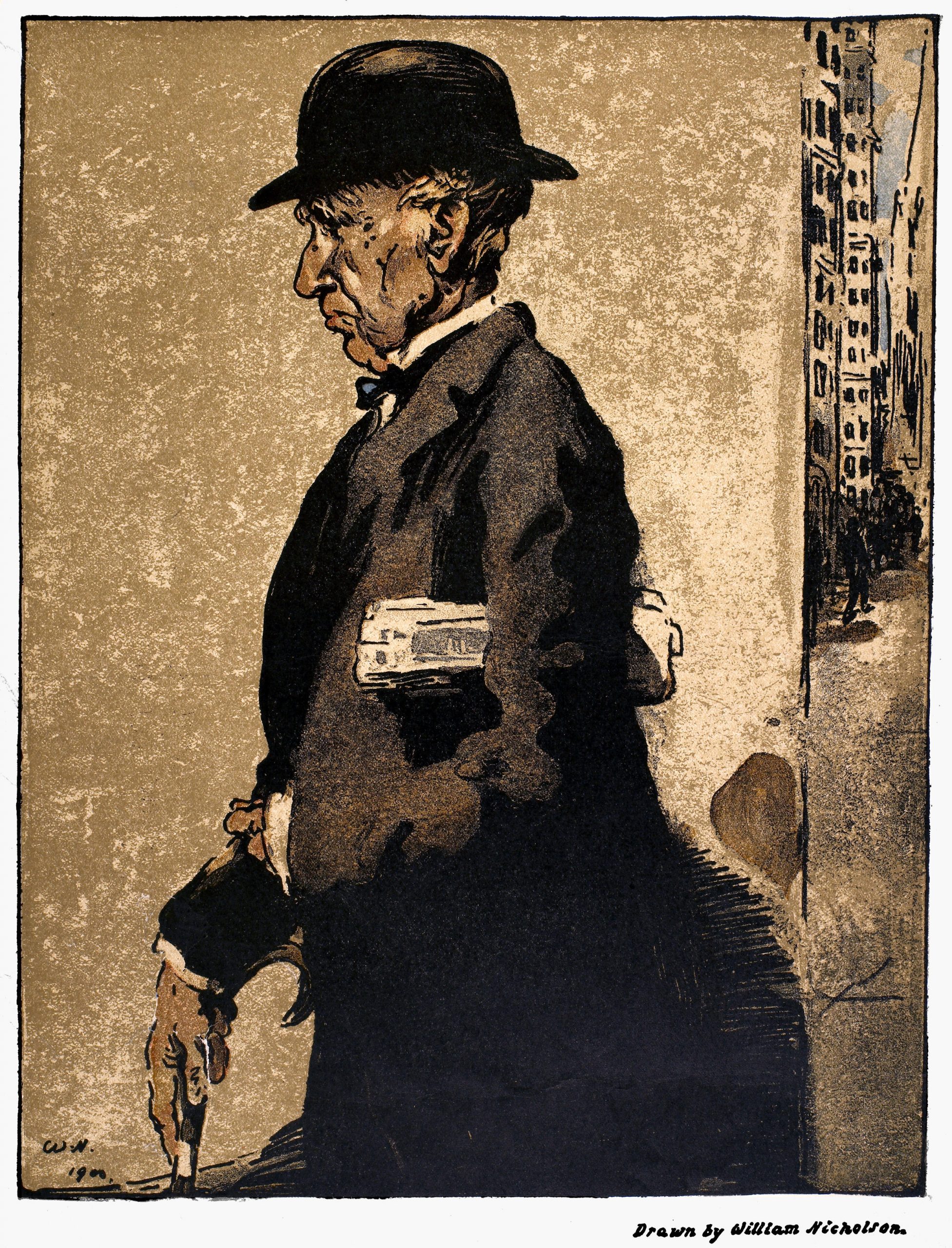

Nicholson established his own reputation as a graphic artist through his skill with woodcuts, producing a series of portraits — most famously his silhouette of Queen Victoria in 1897 — and books, notably for Heinemann, whose illustrated publications featuring ‘types’, such as animals, sports and letters of the alphabet, were then a fad.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In about 1900, he returned to painting and was soon in demand as a portraitist, sharing the arena with Lavery, John and Orpen, with whom he also painted each other and their friends. Commissioned works were mostly of Society figures, although without the Edwardian swagger of Sargent. Nicholson also had a particular skill for children. Often, his sitters look away from the viewer; sometimes they are dwarfed by their setting.

The influence of Velázquez, notably in some of his earlier compositions, can be traced back via Whistler and Manet, whom he also greatly admired. Some of his finest portraits, such as Sir Max Beerbohm (about 1903), Walter Greaves (1917) and Gertrude Jekyll (1920), are masterpieces of psychological penetration in his pared-back style, painted mostly in black and subtle gradations of earth tones.

Despite his success, Nicholson would experience recurring financial difficulties. From 1909, he had a house, a studio and a mistress—his model and housekeeper Marie Laquelle — in London, as well as the old vicarage at Rottingdean. The Sussex Downs, and later those of Wiltshire, where he moved in 1923, were a particular inspiration for his landscapes — small, spare studies painted on the spot with thin, liquid brushstrokes and a muted palette. Often, the sky seems limitless within the restricted space, although in some later examples he uses a high viewpoint, making the land appear to tilt upwards.

These unassuming works feel spontaneous and fresh, but there is often a haunting, slightly mysterious quality, the suggestion of some deeper significance. He also painted many landscapes when on holiday abroad, among them a distinctive group redolent of Sickert and Whistler, showing street architecture and shop fronts, mostly in Paris and Dieppe.

Although Nicholson was not interested in Modernist experimentation, his preoccupation with exploring the boundaries between form and flattened shapes of colour anticipated the abstract works of his son. Not that Ben would have acknowledged this: he perceived his father to be a conventional painter indifferent to developments in serious contemporary art.

Nicholson disliked the politics and debates of the art world and avoided joining painters’ groups or becoming a member of the Royal Academy—‘a label of any sort scares away from me all desire to paint,’ he told Munnings in 1926.

Yet, for all his eccentricities and slightly old-school image, he was debonair, witty (he loved puns), known for his sartorial panache and mixed in artistic and literary circles that included Beerbolm, Kipling, Barrie and Lutyens, as well as his own family — his daughter Nancy was married to Robert Graves; his second wife, Edith, was an artist; Ben was married to the painter Winifred Nicholson and then to Barbara Hepworth.

Throughout his career, Nicholson produced a sequence of poetic still lifes that prove him a master of the genre. He captures the essence of a simple arrangement of flowers in a lusterware jug; a glass, gold or pewter vessel beside a book or gloves, transmitting not only their likeness, but also the decorative qualities of the composition, the subtle nuances of tone and surface in response to light and shadow.

Modest-scaled and unshowy, it is these intimate portraits of objects that are best loved among Nicholson’s works today.

‘William Nicholson: catalogue raisonné of the oil paintings’ by Patricia Reed (2011) is an indispensible compendium of Nicholson’s work. There are at least 125 works by Nicholson are in public collections — visit www.artuk.org

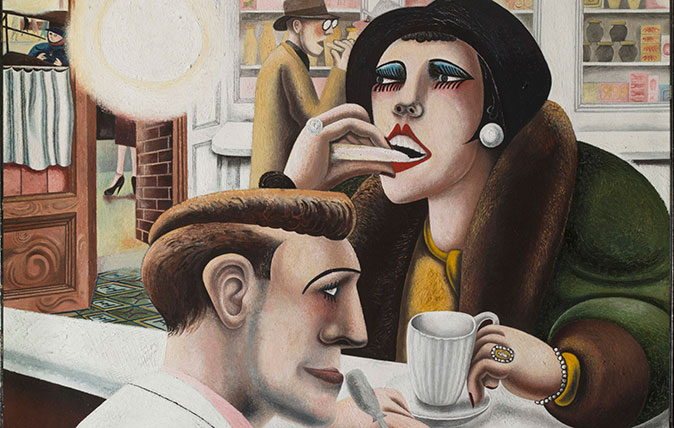

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

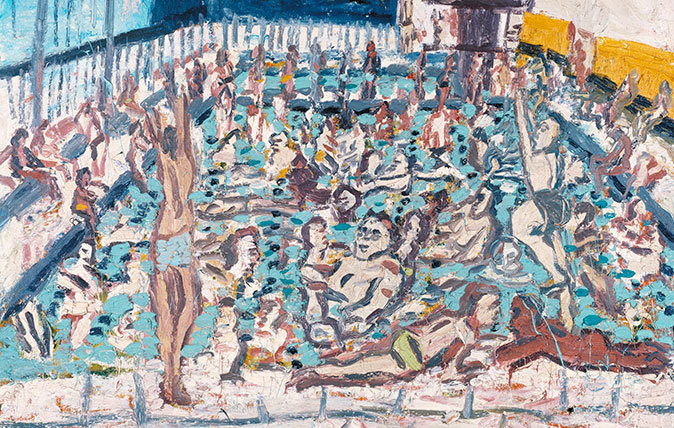

Credit: Leon Kossoff Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon 1971. Tate © Leon Kossoff

In Focus: An idyllic sunny afternoon, evoked by a leading light of the School of London

Lilias Wigan takes an in-depth look at Leon Kossoff's Children's Swimming Pool, Autumn Afternoon, one of the pictures on show

Credit: © Musée Rodin

In Focus: Rodin's quirky take on one of the treasures of the Elgin Marbles

In Focus: Ruskin, Turner and the ‘prophetic warning of impending environmental catastrophe’

Simon Poë is blown away by ‘Ruskin, Turner & the Storm Cloud’ at the Abbott Hall Art Gallery in Kendal,

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.