In Focus: The Glasgow Boys, the Scottish painters inspired by an iconic French Naturalist

Mary Miers revisits the work of a group of rebellious young artists who challenged the artistic establishment and became an international sensation — and who are now the subject of a new exhibition. Pictures courtesy of the Fleming Collection.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For all that the romanticised image of Scotland continues to entrance, in the late 19th century it was challenged by a loose affiliation of artist-friends who, railing against the Victorian diet of darkly varnished history paintings and brooding Highland landscapes, sought out the gentler terrain and steady light of southern Scotland and other climes and blazed a trail with their en plein air scenes of ordinary rural life.

Inspired by the French Realists, the Glasgow Boys, as they called themselves — most were brought up or trained in Glasgow — admired Courbet and Millet, but their hero was Naturalist master Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848–84), who documented French peasant life with dispassionate honesty.

After serving in the Franco-Prussian war, he had retreated to paint village life at his birthplace of Damvillers. Taking their cue from him, the Boys immersed themselves in fishing and farming communities, where they focused on incidental scenes — a hind’s daughter in a mud-clodded kailyard; potato gatherers; a boy herding cattle; children playing; a gaggle of geese — painting without anecdote or sentimentality and with an emphasis on tonality. Some adopted his technique of detailing certain elements in high definition against a more generalised background, his flattened perspectives and broad, square-headed brushstrokes.

In 1883, James Guthrie and his friends Edward Walton and Joseph Crawhall migrated to Cockburnspath, where they formed a summer retreat, Guthrie staying on to paint through the winter.

Over the next two years, others such as George Henry, who had painted with them in the Trossachs, descended on the Berwickshire village, so that, in summer, nearly every cottage had its artist lodger and easels could be seen pitched in fields, gardens and by the harbour.

Meanwhile, in 1883, Belfast born John Lavery, who had studied at Glasgow School of Art, joined a group of artists and writers at Grez-sur-Loing near Fontainebleau. Established in the early 1870s, the colony was a conscious emulation of that created at Barbizon in the 1830s by painters such as Millet and Daubigny.

Lavery was among the young Glasgow Boys — others included William Kennedy, Alexander Roche and Thomas Millie Dow — who had enrolled in the Paris ateliers before moving to Grez. They absorbed first hand the bold brushwork and tonal values of modern French painters, although only Lavery actually met Bastien-Lepage, who advised him always to carry a sketchbook.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A number of female painters with links to Glasgow also shared the Boys’ artistic sensibility and moved in their circle — hence the more apt term ‘Glasgow School’. Their freedom to practise as women artists was encouraged by the enlightened Francis ‘Fra’ Newbery, director of the Glasgow School of Art from 1885. One of his students was Bessie MacNicol, who became a pioneering female artist at the Académie Colarossi in Paris and exhibited with the Boys at international exhibitions before she died in childbirth in 1904.

She is represented in the current show, as is Flora Macdonald Reid, who was linked to the group through her artist brother, John Robertson Reid. An annual exhibitor in Glasgow, she went on to have a successful international career and co-founded the Society of Women Artists. Fieldworkers, completed in 1883 when she was only 23, stands out as a fine example of the genre, echoing works by Bastien-Lepage in its depiction of three men impassively harvesting potatoes.

Constance Walton, from the famous artistic dynasty that included her brother Edward, was another of the Glasgow Girls. A talented watercolourist trained at the Glasgow School of Art, she belonged to the generation of women artists and designers who, together with Charles Rennie Mackintosh, created the city’s second art movement, the Glasgow Style. Her watercolour Day Dreams (1890) uses soft tones to create an atmospheric portrait of a girl with a cat — as with other figures painted by the group, the girl stares out blankly, recalling Bastien-Lepage’s expressionless labourers. By the later 1880s, the group’s focus had shifted. Many moved away from rural Realism to explore other aspects of modern life: the city, foreign travel, portraiture and leisure activities.

Among the different paths taken in this second phase, a memorable moment is the colourful and decorative approach adopted by the younger Hornel and Henry after they had abandoned Naturalism in favour of a more Symbolist style inspired by Celtic mythology and the work of Monticelli. As do many of the works in this section of the show, they reflect the fashion for Japanese art and, most importantly, the monumental influence of Whistler.

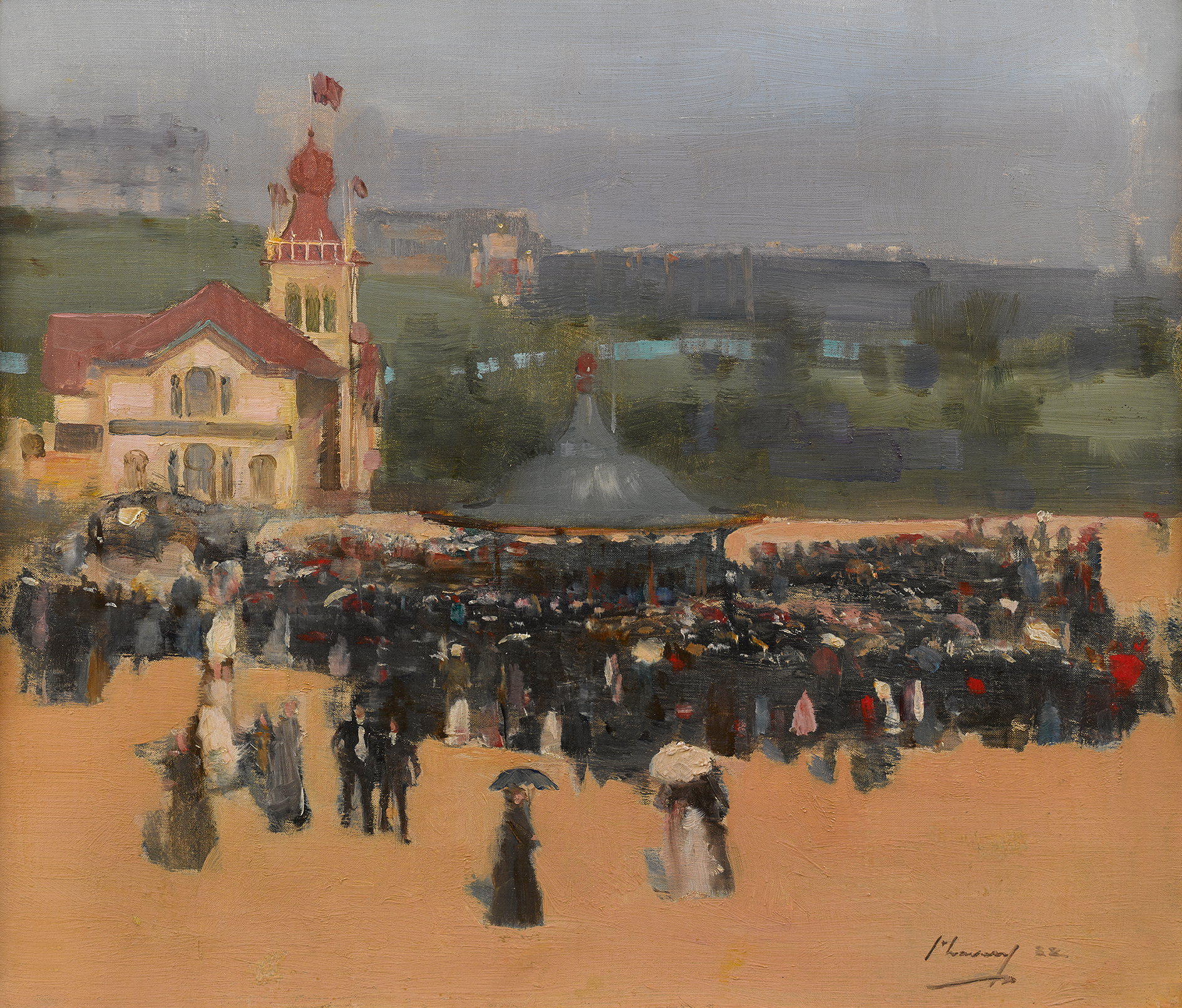

Encouraged by the leading art dealer Alexander Reid, the bourgeoise industrialists of the Second City of the Empire welcomed the modernity of the Glasgow School and collected its works as a cultural expression of their civic pride. Public appreciation of the group spread wider in 1888, when Lavery, Guthrie, Henry and others were strongly represented at the Glasgow International Exhibition.

These young, restless painters knew how to harness influencers in the art world and promotion through the press. In 1890, they staged their breakthrough first London show at the progressive Grosvenor Gallery, resulting in widespread attention from European galleries and, in 1895, from America. As James Knox writes in his new book The Glasgow Boys and Girls: ‘[Their] apotheosis in the 1890s established a pattern which has underpinned the discovery and development of cutting-edge artists ever since.’

In this difficult year, when so many museums and galleries have been unable to put on major loan exhibitions, small, themed shows created from existing collections have come into their own. The Fleming-Wyfold Art Foundation’s ‘Museum without Walls’ strategy suits this approach perfectly.

Appropriately launched only 20 miles from Cockburnspath, this touring show of some 35 works represents every significant member of the group during its period of greatest activity — 1880–95. It revisits the theme of a major exhibition held in Glasgow and London in 2010 — ‘Pioneering Painters: The Glasgow Boys 1880–1900’ — which the Fleming Collection, then with a London gallery, complemented with a display of its own Glasgow School works.

To see some of these rarely shown paintings again is to be reminded of how radical the group was in the context of contemporary British art.

As Elizabeth Pennell wrote in 1895: ‘It is from Glasgow… and not from the Scottish Academy and the schools of London, that modern British art has received its strongest impetus.’

‘The Glasgow Boys & Girls’ is at The Granary Gallery, Dewar’s Lane, Berwick-upon-Tweed, until November 15 — www.berwickvisualarts.co.uk. It tours to the University of Hull Art Collection, January–April 2021. ‘E. A. Hornel: From Camera to Canvas’ is at the City Art Centre, 2, Market, Edinburgh, November 7–March 14, 2021 — www.edinburghmuseums.org.uk

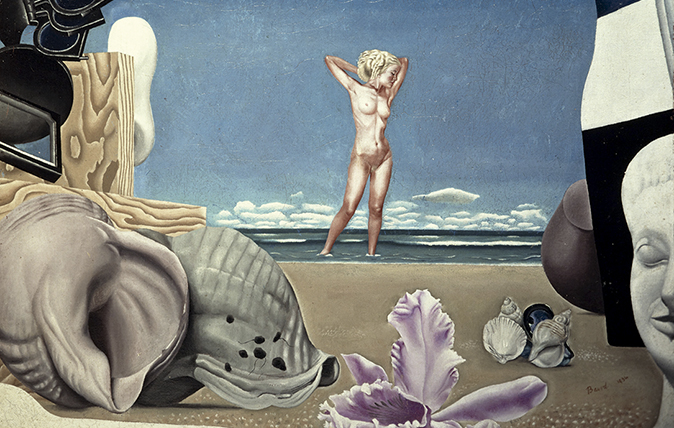

The Scottish artists who mashed up Dali and Boticelli to make their mark in the 20th century

Duncan MacMillan applauds an exhibition that reassesses the contribution made by Scottish artists to the great movements of Modern art.

My favourite painting: Lachlan Goudie

'It’s a series of prompts, unlocking the viewer’s imagination'

Mary Miers is a hugely experienced writer on art and architecture, and a former Fine Arts Editor of Country Life. Mary joined the team after running Scotland’s Buildings at Risk Register. She lived in 15 different homes across several countries while she was growing up, and for a while commuted to London from Scotland each week. She is also the author of seven books.