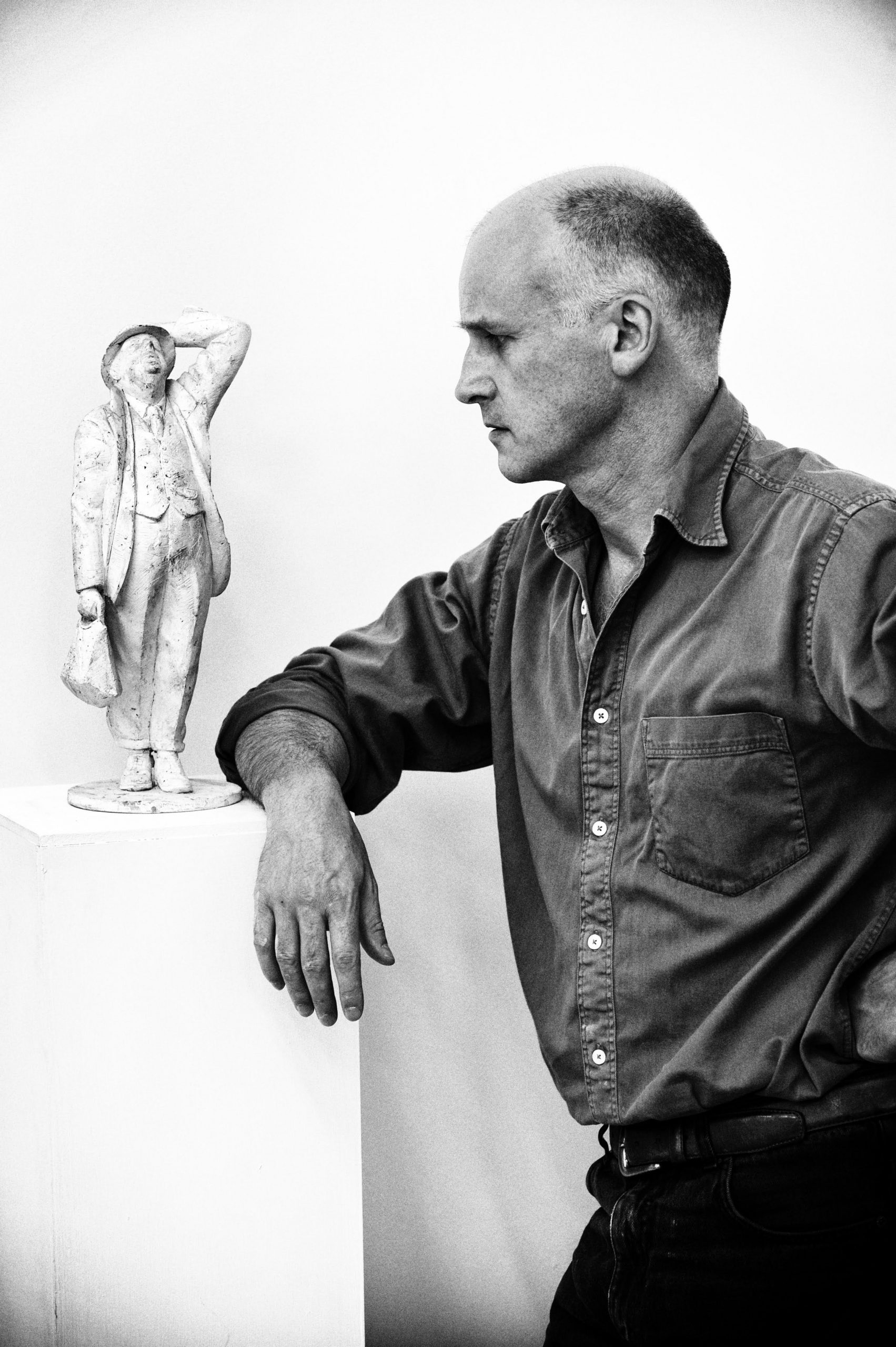

In Focus: The sculptor whose work 'treads that fine line between likeness and caricature'

At a time when public statuary is much in the news, Timothy Mowl considers the work of a leading British figurative sculptor.

Martin Jennings is one of Britain’s most important figurative sculptors. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Sculptors, his subjects include prominent figures from the world of politics, the military, royalty, academia, literature, industry, medicine and the law, his work often incorporating carved inscriptions. He is probably best known for his affectionate statue of Sir John Betjeman at St Pancras Station, which turns ‘the teddy bear-shaped’ poet into a romantic, lyrical figure that has become a celebrated London landmark.

At a time when such figurative statues tend to attract critical hostility from the arts media, yet knowing, but often insipid, conceptual work draws praise, Mr Jennings’s sculpture raises interesting questions as to why new portrait statues are often held in contempt, even when the general public responds to them with warmth and affection.

Maggi Hambling’s 2003 steel scallop shell commemorating Benjamin Britten, which shimmers out of the shingle on Aldeburgh beach, is arresting and challenging, but that’s not to say that a head-on representation of the famous composer could not have been equally rewarding. Rose Garrard’s 2000 figurative sculpture of Sir Edward Elgar caught up in the mental act of composing as he looks out over Great Malvern invites engagement, as does Jemma Pearson’s 2005 depiction of the composer leaning against his trusty Sunbeam bicycle in the Cathedral Close, Hereford. In much the same way, Mr Jennings’s recent statue of George Orwell at the BBC actively admonishes from its stone plinth.

The sculptor is surprised that people embrace his statue of Betjeman for selfies, but the same happens at Morecambe, where Graham Ibbeson’s lively 1999 figure of Eric Morecambe has proved such a success that people have to form a queue to take photographs with it.

Mr Jennings intentionally conveys the ambivalent relationship between subject and context with his statue of George Orwell. He depicts the writer and broadcaster poised on a plinth in readiness to accost passers-by, habitual roll-up in hand, finger-wagging as if from a soapbox. He sees the inscription on the wall behind—‘If liberty means anything at all it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear’—as a ‘challenge to political journalists and to us all’.

Orwell is an ideal subject — ‘several inches over six feet tall, with cabbage-patch hair and a lamentable moustache, consumptive, built like a scarecrow and with a potting-shed wardrobe to match, his physical appearance stands as a joyful counterpoint to a monumental intellectual acuity’. The trick is always to tread carefully that fine line between likeness and caricature.

There’s an obvious conundrum here, however: how to convey fierce intellect in a representational sculpture without lapsing into parody. Mr Jennings has achieved this effortlessly with his Philip Larkin at Paragon Station in Hull. In an echo of the first line of Larkin’s Whitsun Weddings — ‘I was late getting away’ — he has contrived a twist in the poet’s pose to convey haste as he hurries to catch his train. The slate base is extended to imply the shadow cast by the statue — suggestive of ‘the intimations of mortality’ with which the poetry is infused.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As with his Betjeman at St Pancras, poetry is exploited in beautiful calligraphy, which works with the finely observed nuances of character. In attempting to track Larkin’s own poetic journey, Mr Jennings has carved another slate inscribed with the last words of the poem on a wall at the end of the line at King’s Cross.

Far more than other forms of art, public sculpture excites hostility. Before it came to be universally loved, 4,500 residents signed a petition condemning Antony Gormley’s Angel of the North. Early last century, Jacob Epstein had to weather philistinism, anti-semitism and prudishness over his unashamedly naked figurative sculptures on the former British Medical Association Building on the Strand. Fortunately, we live in a more enlightened age, when the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square could display, between 2005 and 2007, Marc Quinn’s sculpture of the disabled artist Alison Lapper, naked and voluptuously gravid.

How do we extend inclusivity to representations of black and ethnic minority figures, especially female ones, in a country where only 15% of monuments are to women? A shining example is Mr Jennings’s monumental bronze of Mary Seacole, the British-Jamaican businesswoman, traveller and healer, who nursed the sick and wounded in the Crimea. She strides purposefully in the gardens of St Thomas’s Hospital by the Thames in London, her innate gravitas enhanced by the huge textured disc cast from shell-blasted Crimean rock that looms up behind her.

Mr Jennings sees his work as an art form wrongly perceived as outdated that can be relevant to our time. He acknowledges that statue making in this country was at its zenith in the Victorian period, but believes we can make figurative sculptures ‘in such a way that they are illuminated by contemporary ways of seeing, rather than those of a century ago’.

Certainly, statues that ‘fetishise a gruesome literalism’, as he would have it, do much to undermine the art form. However, it’s surely time the art establishment broadened its focus on conceptual pieces by a limited number of approved artists and readmitted figurative statues into its perception of sculpture.

Mr Jennings’s subtle and aesthetically informed work suggests there is still much scope for, and public interest in, such commemorative artworks.

Martin Jenning: Life and Times

Born in 1957 in West Sussex and is now based in the Cotswolds near Stroud.

He came to sculpture in the 1980s, through a course at the Sir John Cass School of Art in Whitechapel.

He has been commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery, St Paul’s Cathedral, the Palace of Westminster, the University of Oxford and many other national institutions.

He won the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association Marsh Award for his Women of Steel sculpture in Sheffield (2017) and for his George Orwell at the BBC’s Broadcasting House, London W1 (2018).

He is currently working on a monument for the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire, dedicated to men and women from the Caribbean who have served in the British armed forces.

Find out more and see more of the artist’s work at www.martinjennings.com.

In Focus: The breathtaking sculpture at the V&A with unexplained, frenzied figures writhing in pleasure and pain

Rachel Kneebone's towering sculpture at the centre of some of the V&A's oldest treasures demands your attention in a way

Credit: James Wild / hgbphotos

In Focus: A sculptor creating 21st century art from the detritus of 20th century life

You're more likely to find artist James Wild hunting through a scrapyard than to find him among the normal haunts

In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube

Credit: Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973): <i>Girl Before a Mirror </i>(Boisgeloup, March 1932). New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

In Focus: The Picasso portrait which revealed to the world his 22-year-old muse

The Tate Modern's first-ever exhibition focusing solely on Picasso concentrates solely on a single year in the life of this

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.