The circus performer who literally gritted her teeth to earn success and fame — and inspired one of the great Impressionist paintings of the 1880s

When Miss La La hoisted herself to the top of the circus tent by a rope clenched in her jaws, she dazzled not only crowds across France and Britain, but also Edgar Degas. Carla Passino tells the story of the artiste — and the artist.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

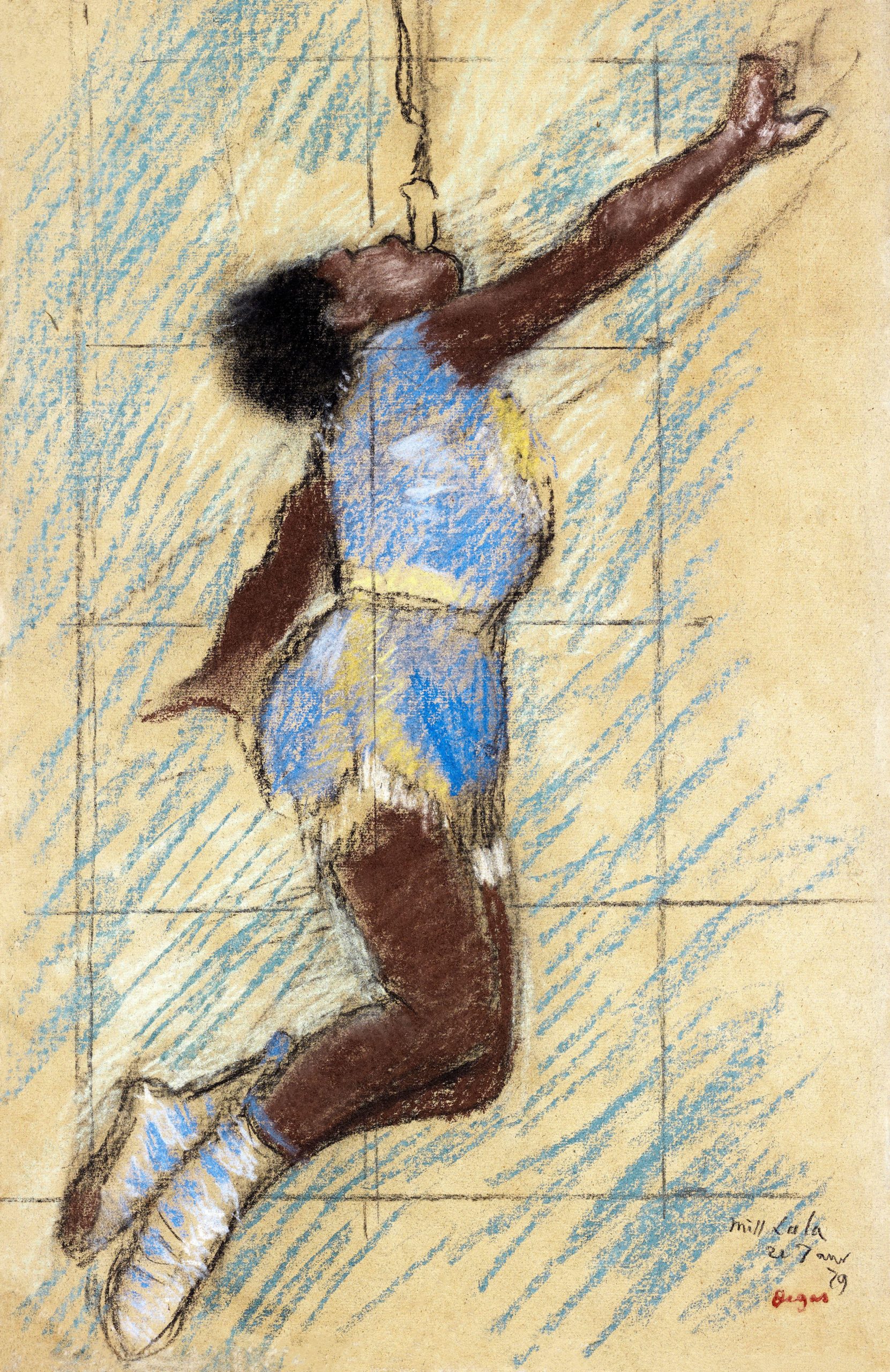

Miss La La floated high above the crowd, the golden frills of her costume shining as she twirled upwards. Her arms pierced the air either side of her body, her legs bent at the knee. Only her teeth, clenching a leather piece at the end of the rope that hung from the top of the circus tent, kept her from plunging to almost certain death. Craning his neck to soak up every detail was artist Edgar Degas, who would later capture the scene in a painting, Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando, now at the National Gallery.

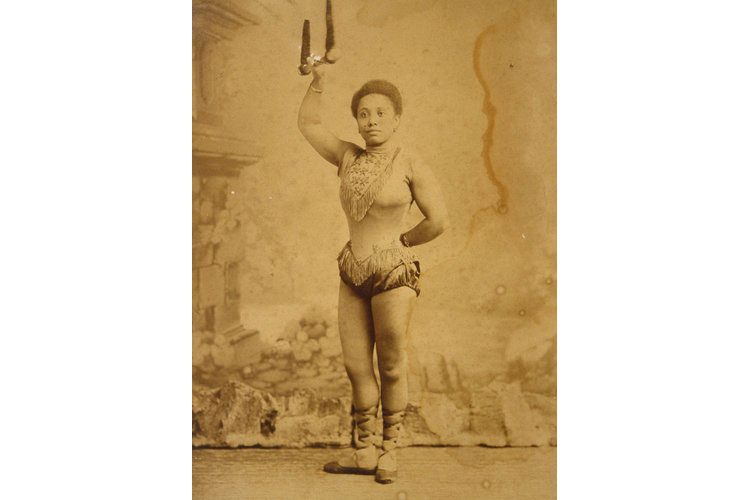

Although the Impressionist is best known for his ballerinas, Miss La La, whose real name was Anna Albertine Olga Brown, was no less of an inspiration to him, as he brought her Iron Jaw act to canvas. The aerialist was born in Szczecin, Prussia (now Poland), in 1858, to a Prussian mother and an African-American father, although, to entice the public, she was sometimes presented as an African princess or even a queen.

She was only nine when she began performing as a trapeze artist and 20 when Degas watched her at the Cirque Fernando, close to his Montmartre studio, for four nights in January 1879. Shortly afterwards, Miss La La went on a tour of Britain, appearing at the Royal Aquarium in March 1879 and, later, the Gaiety in Manchester. Her feats — she spun a man by the belt she held in her mouth, before lifting with her teeth a 150lb brass cannon, to which she hung on even after it was fired mid air — wowed the British public.

On March 15, 1879, The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News named her the latest acrobatic sensation, marvelling at ‘a maxillary power unexampled since the days of Samson’. Her biceps were not to be sniffed at, either, at more than 15in, much to the envy of Edmond Desbonnet, founder of one of France’s early bodybuilding magazines, who praised Miss La La’s ‘superb arms’ in his book on strongmen, Les Rois de la Force.

It can’t have been easy for Degas to convey the aerialist’s strength or her spiralling movement as she ascended to the top of the circus tent and he made many studies from different angles. Paradoxically, however, his greatest challenge was getting the roof right.

He struggled with perspective so much that he called upon an architectural draughtsman for help, according to his friend Walter Sickert. Once that problem was solved, Degas displayed his painting at the 4th Impressionist Exhibition in Paris in April 1879.

Although Miss La La didn’t appear in any other major artwork afterwards, she continued to feature on numerous posters, as befitted a top-billing star — she would go on to perform for about another decade, switching to her given name of Olga. After her double-act partner Kaira la Blanche (Theophila Szterker) fell to her death in June 1888, she married contortionist Emmanuel Woodman and had three daughters, with whom she later formed a troupe, the Three Keziahs. The family settled in Belgium, where Woodman became stage manager at Le Palais d’Eté, until his death in 1915. Four years later, Miss La La applied for an American passport and disappeared into oblivion.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The aerialist’s race and gender inevitably played a part in her career — in Britain, she was a ‘tawny Amazon’, in France, the Black Venus and one of her acts with Szterker was called ‘The Black and White Butterflies’ — but also in Degas’s work. Critics have since examined Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando in the context of both the racial perceptions at the time and the artist’s own biases and familial ties (his mother, Marie-Célestine Musson, a Creole, had black relatives).

Now, a National Gallery display, part of its ‘Discover’ series, delves deeply into Degas’s attitudes to race and the aerialist’s racial identity, as well as examining the development of the painting through a range of material that includes previously unseen pictures of Miss La La and unpublished drawings by the Impressionist painter. Above all, however, ‘Degas and Miss La La’ restores the spotlight on an extraordinary woman who built her own success quite literally by gritting her teeth.

‘Degas & Miss La La’ is at the National Gallery from June 6–September 1 (www.nationalgallery.org.uk)

The 12 most iconic paintings in The National Gallery, by gallery curator Dr Francesca Whitlum-Cooper

Dr Francesca Whitlum-Cooper joins the Country Life Podcast to share how she and the team at the National Gallery picked

The architecture of the National Gallery, 'one of the defining landmarks of London'

In the wake of the re-opening of museums, John Goodall looks at the architecture of the National Gallery in London

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.