Curious Questions: Where have all the acorns gone?

Last year, oak trees shed acorns by the billion — this year, they're almost nowhere to be seen. What's behind the mystery? Martin Fone, author of More Curious Questions, investigates.

The last eighteen months have been a period of changed priorities and reassessment, when what was often taken for granted has become valued. The once irresistible siren call of exotic, far-off lands has given way to an appreciation of the attractions offered by the area in which I live, not least the extensive woodlands just a stone’s throw from my house.

Part owned by the Ministry of Defence and the local council, it is a mix of pine, oak, and sweet horse chestnut, interspersed with a carpet of bracken and heathland gorse and an avenue of rhododendrons. Large enough to allow an escape from the madding crowd, it does present some surprises. Used by the military for training exercises, more so now as even their ability to travel has been restricted, the sylvan calm can be punctured by the popping of gunfire, the sight of camouflaged soldiers and urgent exhortations to get out of the way. Its dense pine woods make it eerily atmospheric, perfect for attracting film crews who nervously protect their elaborately designed sets from the unwary boots of walkers.

While the display of rhododendrons in springtime is spectacular, my favourite season is autumn with its vivid palette of colours, a mix of vibrant golds, rusts, browns, reds, and greens. The wind’s soft summer susurration has given way to a more sinister whistle and the deciduous leaves, forming a thick carpet which increases in depth and composition by the day, rustle and crackle under my feet. Even if only momentarily, the cares of the world seem a million miles away.

Last year I was surprised by how many fallen acorns and sweet chestnuts with their green spiky cases had littered the tracks, adding an extra dimension to the soundtrack of my walk. The gentle thuds as they hit the ground were intermingled with the sharp, intensely satisfying cracks, as their casings split under the weight of my boot.

The technical term for the nuts and fruits that our woodland trees produce is mast, derived from the Old English word ‘mæst’, which was used to describe nuts that had accumulated on the ground and then foraged by domestic pigs. There are two forms of mast; hard, like acorns and beech nuts, and soft, like catkins and rose hips.

By extension, the term mast year is used to describe a year when our woodland trees produce bumper crops of fruit. Infrequent as they are, 2020 was a mast year, oak trees going into overdrive in producing acorns, just as they did in 2013. Our forefathers, whose livelihood and well-being were interlinked with the successful fattening of their livestock, were acutely attuned to the peaks and troughs of mast production. However, to this day its mysteries are still not fully understood.

An acorn is how an oak propagates itself, each nut containing usually just one seed, enclosed in a tough leathery shell, sitting inside a cup-shaped cupule. If the seed germinates, it pushes out a taproot that will anchor the tree for the duration of its existence. The problem, though, is that each seed is full of energy-rich starch, which, while designed to give the seedling its first vital nutrients, presents an irresistible snack for the squirrels, beetles, jays, and the occasional deer that make the wood their home. If the tree is to improve its seeds’ chances of survival, a clever strategy is to overproduce so that there are more acorns than the hungry foragers could possibly devour.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

"Some scientists think that the trees may synchronise the mass production of fruits by releasing some form of chemical signal, as they do to kick start defensive mechanisms when neighbouring species are damaged"

For the oak overproduction brings a further benefit. Adult trees can grow up to 45 metres tall and spread almost as wide and can take up to seven hundred years to reach old age. Its longevity and size mean that it needs to ensure that its seeds travel some distance away. When there is an abundance of acorns, squirrels will obligingly carry them away and bury them rather than eat them immediately, thereby increasing the range over which the seeds are dispersed. The seed only needs to fall into the hands of an amnesiac squirrel or one that falls into the clutches of its own predator to increase its chance of survival. Depending upon the species, an oak will start producing acorns when they are between twenty and thirty years old, reaching peak acorn production when they are between 50 and 80 years of age. Over its lifetime, an oak will produce around ten million Even so, precious few make it even to the sapling stage.

Producing a bumper crop of acorns comes at some cost to the tree, making significant inroads into its store of sugars and starch. To replenish its store of starches, the oak needs a period of recuperation, forcing it to concentrate on less demanding activities, such as increasing its production of leaves and wood, and this explains why, unlike last year, there is a noticeable absence of acorns.

This follows the pattern that was observed in 2014. While in 2013 the branches of oaks were bowing under the weight of their crops of acorns, the Forestry Commission was reporting the following year that there were barely any. 2021 has all the hallmarks of being a fallow year in the masting cycle.

As well as providing the oak with a well-earned rest, this will have an impact on the population of those creatures that feast on acorns. Although a mast year will mean that predator populations increase, a run of lean years will put pressure on numbers so that by the time the next mast year occurs, there are fewer predators to eat the seeds, thereby further enhancing the chances of the seeds germinating. Clever, really.

It is still a matter of some debate as to why mast years occur precisely when they do and why all the trees seem to synchronise their behaviour. One theory is that weather conditions have an important part to play in the process. A cold spell during spring will freeze the tree’s flowers, upon whose pollination it depends to produce acorns. Similarly, a dry summer will kill the developing seeds and force the oak to close the pores in their leaves to conserve water, reducing its ability to make carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. While 2020 saw a dry spring and a wet summer, ideal conditions for the oak to develop its crop of acorns, this year’s weather has been almost the reverse. As all the trees in a particular area experience the same weather conditions, it makes sense that these climatic triggers will influence their behaviour in the same way.

Intriguingly, some scientists think that the trees may synchronise the mass production of fruits by releasing some form of chemical signal, as they do to kick start defensive mechanisms when neighbouring species are damaged. Whatever the reason, our local frugivores have had a bumper crop of acorns to feast on and, who knows, some seeds might even survive to produce the next generation of the mighty oak, that most distinctive and ancient symbol of our woodlands. Let us hope so.

Acorns may be thin on the ground this year, but it will only be a matter of time before the masting cycle turns full circle again.

Martin Fone is the author of several books including 50 Curious Questions and 50 Scams and Hoaxes. His latest book, More Curious Questions, is out now.

Curious Questions: Is the chocolate side really the top of a Jaffa Cake?

Martin Fone discovers nothing is quite as it seems in the world of Jaffa Cakes — including whether they are

Credit: Rex

Curious Questions: How do you take a group photo in which nobody is blinking?

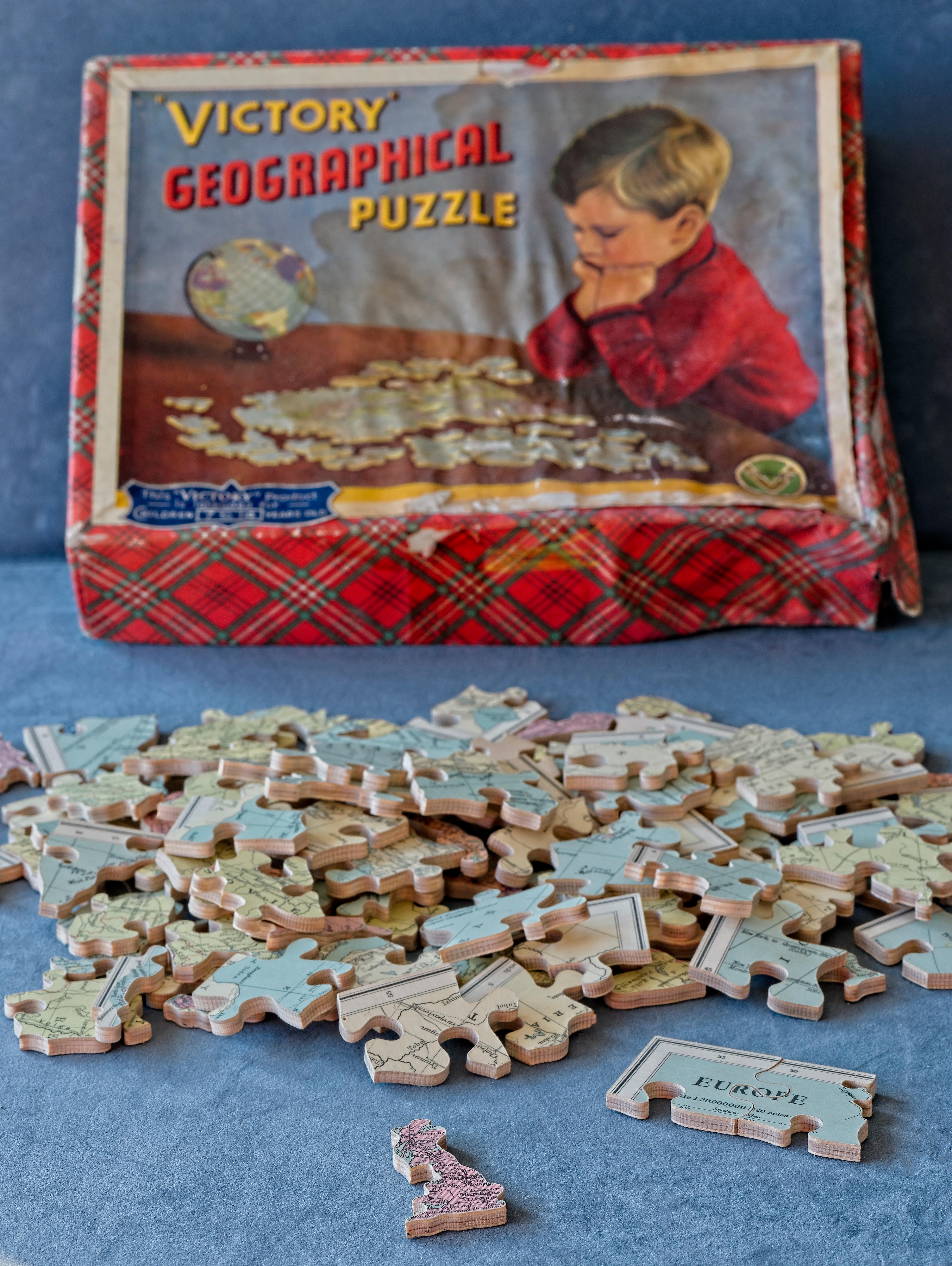

Curious Questions: Why do we call picture puzzles 'jigsaws'?

Jigsaws have been around since the 18th century and have gone through all sorts of iterations. Martin Fone traces their

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Curious Questions: Who invented the lawnmower?

Martin Fone delves into the history of the lawnmower and discovers a link to weaving machines.

Curious Questions: How likely are you to be killed by a falling coconut?

Our resident curious questioner Martin Fone poses (and answers) another head scratcher - or should we say, head banger?

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.