Sir David Attenborough’s record-breaking Nature documentary reveals the devastating effects of bottom trawling on our oceans

Bottom trawling is a disaster for fish stocks, but it also releases previously stored carbon back into the atmosphere.

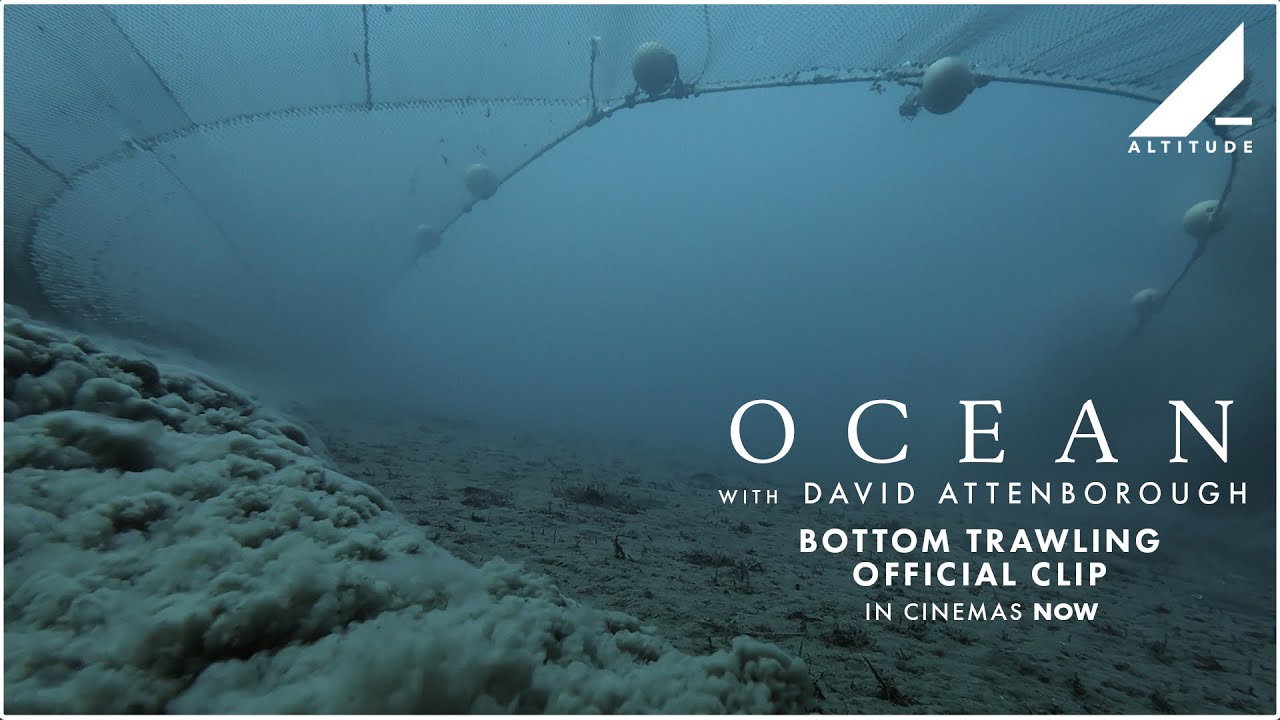

In his latest blockbuster, Ocean, Sir David Attenborough reveals the brutal reality of bottom trawling: a camera tracks a 30 ton metal net, weighted by doors and chains, as it scours the seabed at terrifying speed, hoovering up everything in its path. Unwanted fish – bycatch – are later discarded, often dead or dying. A 2022 study by the World Wildlife Fund concluded that of all the fish discarded in the EU, 92% were caught by bottom trawling.

The revelatory footage is shocking, but voices have been raised for many years in protest at the destruction caused by this method of fishing which targets fish such as cod, pollock and hake that live on the seabed. In 1866 a royal commission heard from fishermen complaining that trawling ravaged fish stocks. Back then it was done from 40ft wooden boats with nets a few metres wide; as boats and machinery got bigger and more sophisticated fish stocks continued to fall. In his 2012 book Ocean of Life, biologist Callum Roberts notes: ‘For every hour spent fishing today, in boats bristling with the latest fish-finding electronics, fishers land a mere 6% of what they did 120 years ago.’

But fish stocks are not the only casualty; by ripping up the sea floor bottom trawling releases plumes of stored carbon into the water and eventually into the atmosphere. According to a 2024 study by an international team of climate experts, the amount of carbon dioxide released into the ocean from bottom trawling is similar to the annual emissions from global aviation.

It is estimated that between 63 to 273 million sharks are the victims of bycatch every single year.

As well, between 40% and 45% of carbon dislodged by trawling remains in the water, leading to acidification of coral reefs and creatures with shells which struggle to breathe because of reduced oxygen. Dr Enrik Saler is the National Geographic explorer in residence and a member of the study team: ‘Tackling these [emissions] is critical to slowing the warming of the planet… Right now countries don’t account for bottom trawling’s emissions in their climate action plans.’ This seems astonishing and something that COP26 will surely have to engage with.

At the UN Ocean Conference in Nice, France, in June, member states will reiterate a principle to protect 30% of oceans from destructive fishing by 2030. But such schemes require policing to prevent widescale poaching of protected areas, otherwise they are what conservationists dismiss as ‘paper parks’. Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) are designed to limit damage to sensitive habitats such as reefs and sea grasses, and to rebuild threatened fish stocks. Yet a report in March 2024 revealed that bottom trawling is still happening in 90% of all offshore areas. Currently only 3% of MPAs are in the ‘highly protected’ category.

Under its blue label scheme, the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certifies fish caught by approved methods. It states: ‘Bottom trawling is an efficient way to catch large quantities of fish and shellfish living on the sea floor, which are needed to feed a growing global population. Around a quarter of all wild-caught seafood is caught via this method every year.’

We asked George Clark, programme director for MSC UK and Ireland, how he could defend bottom trawling. ‘Although impactful it can be managed responsibly,’ he argued, ‘there are numerous examples of fisheries improving practice as a result of MSC scrutiny.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It is also more affordable and the overwhelming majority of retailers sell bottom trawled fish. Often, only the more high-end, small stockists can be trusted and it’s typically to avoid the massive cod and hake — usually from Iceland or China, and frozen — import fees.

Footage from the Ocean film was indeed dramatic, Clark agrees, ‘but fisheries also use cameras to assess the impact of their practice and adjust their gear to avoid certain fish or give them an escape route.’

‘Fish is an expensive protein — a move to lower impact, small-scale fishing would rule out the opportunity for many people to eat and enjoy fish.’

Jane Wheatley is a former staff editor and writer at The Times. She contributes to Country Life and The Sydney Morning Herald among other publications.