Solving the mysteries of the countryside, from hair ice and cramp balls to pillow mounds and the sheepwash with a 16ft drop

Naturalist John Wright has all the answers to our most unusual countryside mysteries.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It must have been in 1956 when my grandmother announced her intention to rise early the next morning to pick mushrooms from the field near our Hampshire village. ‘They only grow overnight, so I need to be there before anyone else,’ she declared. Born in 1896, this was a girl of the Wiltshire countryside, so I presumed she knew what she was talking about.

Still, it seemed odd, even to your then five-year-old correspondent. How could anything grow that fast? The whole business worried me for decades.

This conundrum was to be the first of many that have attended my countryside walks over the years. I was destined never to rest when confronted by a mysterious lump on a leaf, the centre of a flower that should have been pollen-yellow, but was black, strange mounds of grassed-over soil, endless holes in the ground for no apparent reason and the massive terraces that march up the chalk hills of southern England.

I am by no means alone in this lifelong obsession and, like every obsessive, wonder at those who do not share my preoccupation. Some people pass by everything, examine nothing, question nothing and waste their time on trivial matters such as earning a living and looking after the children.

I jest, of course, but relatively few rural wanderers know what a plant gall is when they see one, or a rust or smut fungus, or could name or explain many or any of the half-dozen or so types of twiggy/lumpy constructions that they observe clinging to trees.

In February last year, I was well into the armchair research needed for a new book on British grasslands when my plans for a couple of months out and about doing (quite literally!) field research in various far-flung British locations became impossible. My book was already late, so shame dictated that I offer my ever-patient publisher a ‘slim volume’ in its place — although not, it transpired, as slim as planned. This gave me the opportunity to write about the mysteries that had engaged so much of my attention and an idea I had long mused upon.

I settled on 47 (a neat prime number) ‘puzzling’ features, about half of them natural — such as the aforementioned rust fungi, mushroom rings, slime moulds, hair ice, honeycomb worms, dodder and cuckoo spit — and half manmade, such as water meadows, pillow mounds, salterns and marl pits. The criterion for inclusion was that the average person would be bereft of an explanation of what something was or how it worked.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Although diminishingly few would recognise the green/brown jelly occasionally seen on damp lawns and paths as the cyanobacterium Nostoc commune, most will know a water meadow when they see one. Yet how, precisely, do water meadows work? How they operate is fascinatingly complex and, in truth, merely a component of the practice known as ‘sheep-corn husbandry’. Water meadows were essential for producing corn, a much more important commodity than sheep.

One of the great joys of learning what things are is the opportunity it affords to explain them to everyone else. Naturally, in delving so deep with my research, I have learned a great deal that was unknown to me. Cramp balls (round, black fungi found on ash trees), about which I thought I knew everything of interest, are vastly more complex than I had countenanced. My favourite revelation, however, was another fungus, choke — and I have accosted the ladies in the corner shop and old friends in the street or on the phone with its detailed story. My wife has now forbidden utterance of the word ‘choke’ in her presence.

Choke is fairly uncommon, visibly at least. It spends most of its time within grasses, only becoming visible when it produces its sexual apparatus. Some species are never visible, as they only ever reproduce asexually by the simple technique of growing into grass seeds.

The sexual stage is first visible as a 1½in-long, white sheath of fungal mycelium on a grass stem, turning orange when mature. The spores (spermatia) are transferred between infected grasses (for mating purposes) by a Botanophila fly that has consumed fungal mycelia and spores.

The fly is discouraged from greedily eating too much of the fungus, which will defend itself by withdrawing its routine production of antimicrobials that usually protect the fly from endemic Wolbachia bacteria. For tolerating all these goings-on, the grass receives multiple rewards from the fungus, including protection from grazing (bitter flavour) and more vigorous growth.

Overall, this is an amazing example of a four-way ‘mutualism’ where everyone wins. All organisms have such stories, but the human artefacts of the countryside come with much more personal tales.

Most villages and many towns will have sported a ‘pound’ throughout much of their history. Many still exist or are remembered in local street or house names. They were places where stray animals were taken to await their owner or, if they had been confiscated in lieu of rent, to await sale by auction. One such auction of confiscated stock took place in Kilmeague, Ireland, in 1826, during British rule.

Fearful of trouble, the authorities brought in 500 constables, enough soldiery to fight a small war and the odd 24lb cannon situated on nearby hills, just to be sure. This may all seem excessive, but 20,000 locals travelled to Kilmeague to support their countryman. The auction took place at the pound and was imaginatively boycotted. Spurred on by cries of ‘Never! No tithes!’, those who might have bought the animals bid no more than a fraction of their value (about 4%), resulting in a near total loss for the landlord to whom tithes were owed.

Miraculously, the day passed peacefully. In a nice addendum, the ordinary British soldiers, no doubt sons of farmers to a man, took to chanting ‘Never! No tithes!’ on their way back to barracks.

A similarly rural construction comes in the form of the sheepwash. Although the standard 10ft-diameter, 5ft-deep sheepwash, complete with channels and sluice-gates, is the most common, a still extant ‘sheepwash’ once used in Wales is the most fun; for the human observer, at least.

It consists of a bridge over the River Ogmore at Bridgend in Wales that sports a couple of small, rectangular holes in the parapet, through which sheep were encouraged to exit (they were pushed). After a fall of about 16ft, the possibly traumatised, but clean sheep were led to the bank for a shot of brandy and a sit down. I made the last bit up.

And those mushrooms? Mushrooms grow at a fairly steady pace. What happens is that a field will be picked clean the previous day, leaving the field apparently bare of mushrooms. However, some of those that are still hidden in the grass as closed-caps will expand (adding little or no dry weight), the stem extending a little and the cap opening. They merely appear to have grown overnight because they were not visible the previous day.

Grandma Stacey was still right about one thing, however. ‘Other mushroom hunters’ are a breed for whom a particularly virulent and instinctive hatred is always reserved. Getting there first is an essential strategy.

John Wright’s latest book, ‘A Spotter’s Guide to Countryside Mysteries: From Piddocks and Lynchets to Witch’s Broom’, is published by Profile Books (£14.99)

Credit: Picfair

Mystery solved: Why nature loves the hexagon, and why without it you'd be a puddle of goo

The hexagon abounds in the natural world. John Wright investigates why.

Credit: Country Life / Fiona Osbaldstone

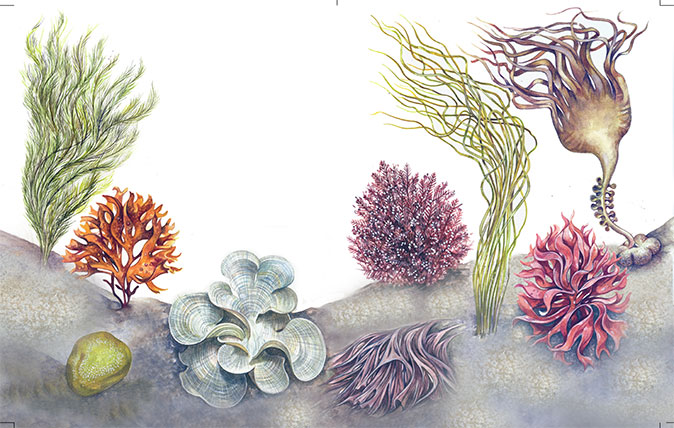

A simple guide to the seaweed of Britain

Naturalist John Wright explains what to look for when you come across seaweed on Britain's beaches this summer.

Credit: Getty Images

Is it possible to live off vegetables and fruit from your garden all year round?

John Wright considers how we could all do more to make the most of home-grown produce.

A beginner’s guide to fermentation: ‘After two days it smelt distinctly cheesy, but better at least than the dead-badger smell I was expecting’

From sauerkraut and kombucha fruit leather to pickled plums and honey marmalade, the art of fermentation is one well worth

Cooking with mushrooms: Tips & tricks

From sautéeing slimy wood blewits with garlic and cream to shaping tempura parasols, mycologist John Wright knows all the tricks

Credit: Paul Mansfield Photograpy/Getty Images

Britain's beautiful green lanes: The charming remnants of leafier times, untouched by the modern world

Although they’re difficult to define, the charm of a green lane – be it a footpath, bridleway, byway or road

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

12 foods you can forage from the great outdoors – no panic buying required

No need to panic buy – the land will provide everything you need, or, at least, a few bits and

12 of Britain's most beautiful butterflies – and the truth about their chances of survival

Beautiful, delicate and harmful to no-one, our iconic butterflies are facing an increasingly perilous existence – that's the conclusion reached

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.