Are we facing 'Insectmageddon' or is it too soon to worry? Experts split over latest bug research

There's good news and bad news from the insect world in two recent reports that paint different pictures of the plight of insects around Britain. Carla Passino explains.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In the same week that research from the University of York restores hope for embattled moths, another report, commissioned by the Wildlife Trusts for the University of Sussex, warns of an ‘invertebrate apocalypse’.

Using the Rothamsted Insect Survey, one of few long-term data sets available for insects in the UK, the York scientists tracked changes in the biomass of moths — essentially, the combined weight of those caught each year at 34 UK sites — between 1967 and 2017. They found that, although the figure has been decreasing since 1982, it’s about twice what it was in 1967.

‘Moths have been in decline for quite a long time now and that is a concern,’ says lead author Callum Macgregor, ‘but to suggest that they’re about to disappear entirely — the data does not seem to support that.’

Because moths are often viewed as an indicator of what’s happening in other insect populations, the results make Dr Macgregor hopeful that the UK is not yet facing ‘Insectageddon’.

He doesn’t dispute the decrease in invertebrate numbers, but he says that the pattern of change may be ‘a little more complex than people have previously been suggesting’, noting that scientists need more ‘good, standardised, long-term data sets’ to further investigate this trend; unfortunately, ‘we don’t have very many of them’.

'We definitely don’t have time to start monitoring insects for 25 years because there may not be many left by then'

Dave Goulson of the University of Sussex counters that we may not have time to wait for the results of long-term studies. Prof Goulson wrote the second paper published this week, which reviews evidence from existing research and draws stark conclusions.

It suggests insect populations may have halved since 1970, with about 400,000 species now at risk of extinction. ‘Long-term studies are great, but we definitely don’t have time to start monitoring insects for 25 years because there may not be many left by then. We’re losing about a species an hour.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Both academics agree changes are necessary. Prof Goulson suggests making gardens, urban areas and public green spaces more wildlife-friendly would make a significant difference. The final piece of the puzzle for him is to help farmers produce food in a more insect-friendly way, not least by linking public funding to environmental protection.

Dr MacGregor says the fact moths ‘bounced back and increased quite drastically’ in the 1970s is an encouraging sign that ‘the right changes to the way we interact with our environment’ could help reverse the decline. ‘If we react in the right way, yes, there probably is some hope.’

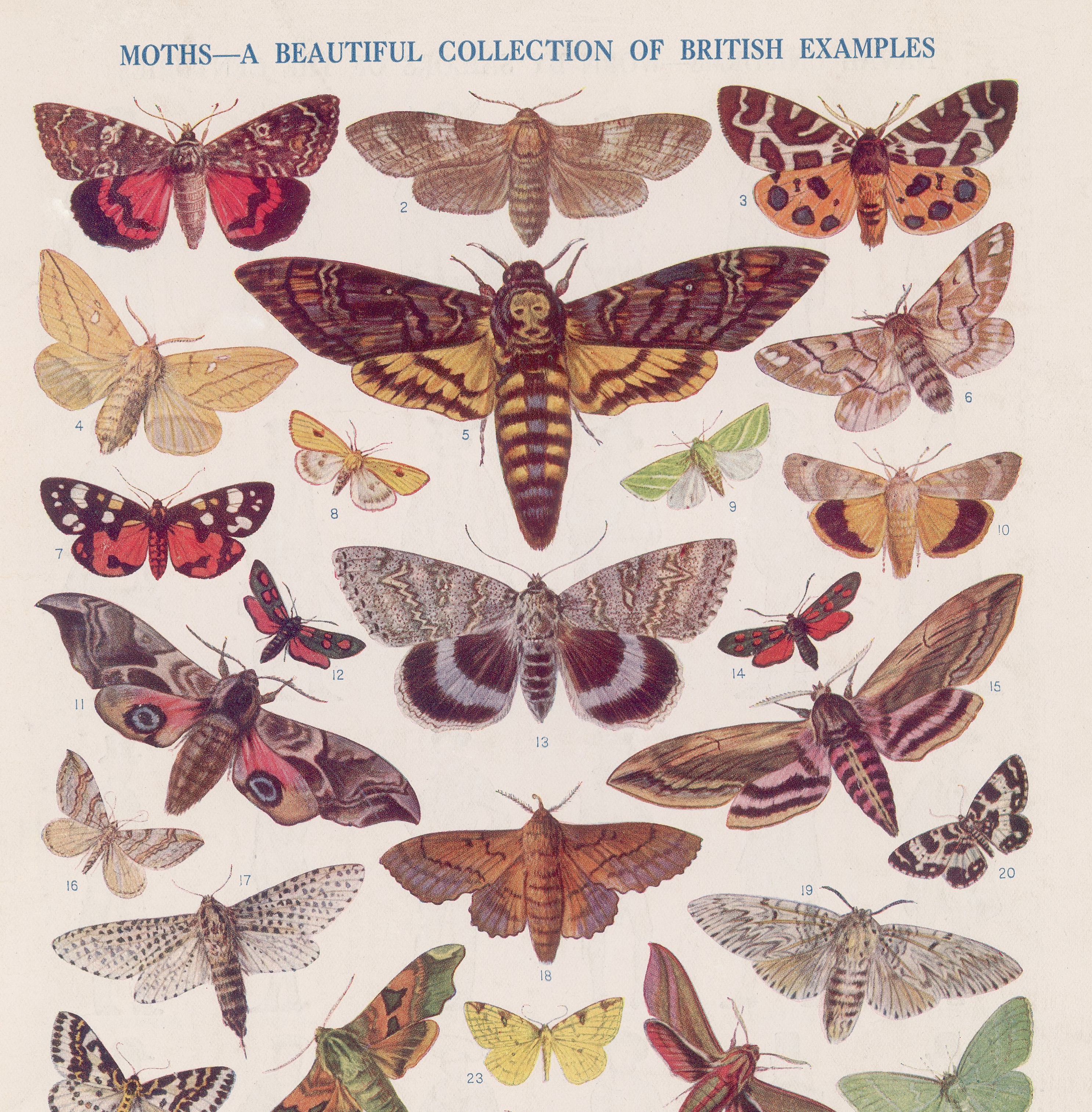

A simple guide to identifying British moths

They might not be considered as beguiling and romantic as butterflies, but we should look at moths in a new

12 of Britain's most beautiful butterflies – and the truth about their chances of survival

Beautiful, delicate and harmful to no-one, our iconic butterflies are facing an increasingly perilous existence – that's the conclusion reached

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.