Military dogs: The non-judgmental companions who are capable of bravery far beyond the call of duty

Working in hostile and high-pressure environments across the globe, military working dogs build enviably strong relationships with their handlers, finds Madeleine Silver.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Bellowing ‘Fire’ when on patrol in Afghanistan had its problems, but when the dubiously christened black labrador arrived at the 1st Military Working Dog Regiment (Royal Army Veterinary Corps) from America, it was too late to change her name. Alarming as it was, it at least escaped the embarrassment laden on one German-shepherd protection dog named Schillag (pronounced ‘slag’).

Either way, the names of canines working across the British military – whether patrolling bases or detecting explosive devices and illicit materials – are central to their identity as they form unwavering bonds with the people who work them.

‘These dogs are absolutely dedicated to their handlers. It’s very important that we consider them as a team,’ says Col Neil Smith, chief veterinary and remount officer. ‘Dogs can pick up on people’s moods and feelings, so there is very much that handler-dog bond. They’re extremely loyal to each other.’

On Fire’s first tour of Afghanistan, her resilience was tested when an Improvised Explosive Device detonated as she worked in front of a patrol, in December 2011. She was severely injured down the right-hand side of her body, with a cracked jaw, a cracked bone beneath her eye and fractured metacarpals. She was medically evacuated to Camp Bastion and then was sent to the Defence Animal Training Regiment in Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire, where she recovered after months of care.

‘Just as soldiers have a medical support system if they’re injured, so we are also here to provide veterinary support,’ says Col Smith, who took Fire on as a pet once she retired. ‘The dogs are treated in the same way as the soldiers – their health and welfare are absolutely key.’

In the heat of Afghanistan, where dogs are still deployed with British regiments in their non-combat role to train, advise and assist Afghan forces, accommodations are made to make the dogs’ lives easier and safer. Pools are installed in the compound for cooling off and ‘doggles’ are distributed for eye protection.

Ambitions for Fire to help in training the next generation of handlers floundered. ‘She kept going lame, so we retired her, but, after that, she stopped doing it – she was a very clever dog,’ laughs Col Smith.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As a wounded warrior herself, Fire was asked to be the mascot for the British team at the 2014 Invictus Games and, in the same year, she collected the PDSA Dickin Medal – considered the animals’ Victoria Cross – on behalf of Sasha, a labrador that, together with her handler LCpl Kenneth Rowe, was ambushed by the Taliban and died in 2008.

‘Fire and I became very close and, when she died last year of cancer, I felt her loss very strongly,’ reflects Col Smith.

For Warrant Officer Jonathan Tanner of the RAF Police, such intimate relationships between dogs and handlers are inevitable – and necessary. ‘If you’re working with a dog for up to four or five years, you can’t help but form a strong relationship with them,’ he says. ‘We can’t make them work if they don’t want to, so it’s imperative that a good, strong bond is formed. We need a mix of intelligence, curiosity, agility, stamina and a willingness to please.’

After 30 years in the Forces, it’s a young German shorthaired pointer called Hertz that sticks with WO Tanner. ‘Hertz was used to detect the presence of electronic communications devices, such as phones, radios and their component parts, to help against the insider threat – a type of search that had previously been undertaken in prisons, but which had never been used by the British military,’ he says.

‘After some trial and error and six weeks of hard work, we managed to get him to an acceptable standard and we deployed to Afghanistan. Hertz left the country after two tours with a total of more than 50 individual finds and more than 100 items of contraband to his name. There’s no doubt he contributed significantly to reducing the number of potential attacks on British and Coalition personnel – I was very proud of him.’

For patrol dogs that guard military bases from the Falkland Islands to Cyprus and up and down the UK, it’s their size and aggression that’s relied upon. ‘The real effect of these dogs is that they’re a massive deterrent – people don’t want 35kg [77lb] of animal on the other side of some fairly sharp teeth coming at them,’ says Col Smith.

In the dogs’ search and detection roles, it’s their acute sense of smell that is utilised: ‘There’s no vapour- or scent-detector equipment that is as sensitive as a dog.’

‘A dog can tell if an explosive is buried somewhere – they are really smelly – and they can tell that someone is hiding in a building from their scent, but the thing we’re actually training is how they tell us what’s there,’ confirms the commanding officer of the 1st Military Working Dog Regiment, Lt-Col Neil Lakin. ‘With some of the dogs, it’s how they sit, how they stand or how they point with their nose. It’s not always as obvious as their simply barking at something and that’s where the bond with the dog’s dedicated handler comes in.’

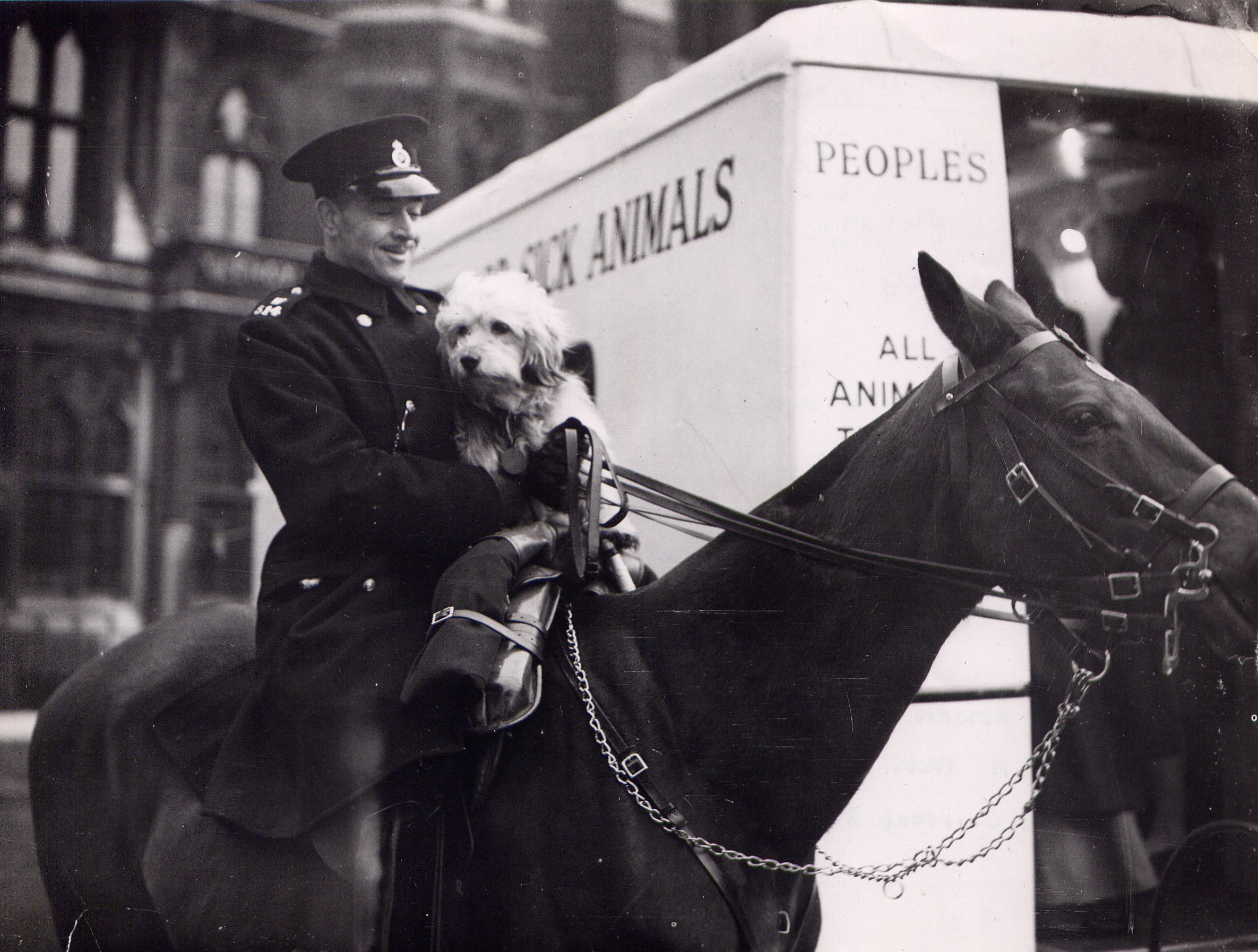

At military bases across the globe, dogs have another, unofficial role: boosting morale. ‘In wartime, a dog can be an iconic reminder of the comforts of home, the fireside warmth of family so far away,’ states author Isabel George, who has written extensively about animals in war. ‘Dogs, the eternal levelers, the non-judgmental companions capable of bravery beyond the call of duty, can display a quality of character that distinguishes the extraordinary from the ordinary.’

When cocker spaniel Sam was crowned the Public Service Animal of the Year in 2017, at the Animal Hero Awards, he was credited not only with saving lives on the battlefield in Afghanistan, thanks to his ability to sniff out explosives, but by boosting injured soldiers’ morale in the medical centres.

‘You have to be careful, because the dogs still need to do their job and not turn into a plaything,’ says Lt-Col Lakin, ‘but this is the British Army and it’s well known that the British all love dogs. There’s nothing like a ginger cocker spaniel bouncing around to boost morale and brighten things up!'

Credit: Sarah Farnsworth/Country Life

Fox-red labradors: Why red is the new black

From russet red to ever-so-slightly blushed, the fox-red is growing in popularity across the country sporting world. However, the gundog

Credit: Alamy

Dog-friendly London: Where to eat, shop and stay with your four-legged friend

Planning a trip to the capital, but don’t want to leave the most important member of the family at home?

Tibetan terriers: Friend to the famous, lovably lively and perhaps the Kennel Club's best-kept secret

They have a starry following, but characterful Tibetan terriers are still a well-kept secret. Emma Hughes meets the best dog

Seven things you need to know if you're getting a wire fox terrier, from stealing food to undying loyalty

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.