Incredible things you never knew about duelling, from Wellington and Lincoln to poisoned sausage at 12 paces

Only a few generations ago, our forebears were prepared to shoot each other when affronted. Ian Morton reports on man’s fatal attraction to the art of duelling.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Although ordinary fellows tended to square up on the spot to settle a disagreement, the most influential of sporting gentlemen – who owned huge tracts of land, as well as the folk who lived there, and who hunted, raced, shot and gambled together – were inclined to act out, at an agreed time and place, a ritual that could well prove fatal.

Winning wasn’t always good news

Some 1,000 duels with powder and ball were recorded between 1785 and 1845, about one in five resulting in a fatality. And not always one fatality, either: several ‘winners’ were subsequently hanged for murder.

Reasons for duelling could be trivial

The poet Lord Byron’s great-uncle killed his neighbour and cousin William Chaworth in a rapier duel in 1765, over a dispute about the quantity of game birds each had on his land and the best way to hang them. Byron was fined.

Grantley Berkeley, heir presumptive to his brother the 6th Earl of Berkeley, was even more incensed by a criticism of his book about Berkeley Castle in Fraser’s Magazine. He thrashed the publisher and had the critic, Dr William Maginn, face him over pistols. Maginn received a flesh wound and the Berkeley honour was satisfied.

Defeating Napoleon didn’t put the Duke of Wellington off duelling

The Iron Duke was a keen country sportsman in the years after the Napoleonic Wars, an while he was a sought-after guest, not all his visits were without blemish. In 1823, he managed to hit his host Lord Glanville in the face and, at Lady Shelley’s, his shot reached a tenant who was hanging out her washing. His hostess declared: ‘You have endured a great honour today, Mary – you have the distinction of being shot by the Duke of Wellington.’ Mary’s grateful response is not recorded.

In March 1829, Wellington – by then Prime Minister – took umbrage when his parliamentary bill to allow Catholics into government after 200 years provoked criticism from the Earl of Winchelsea. The duke called him out and they met at dawn on Battersea Fields. As challenger, the duke fired first, aiming wide, and the earl then discharged skywards.

Even great statesmen became duellists

Wellington was not the only British prime minister to duel. William Pitt faced George Tierney on Putney Common, both missing, and the Earl of Shelburne and George Canning also survived ritual combat.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Future US President Andrew Jackson fought several duels and killed a famous marksman, Charles Dickinson, in 1806. Abraham Lincoln and an adversary were dissuaded by their seconds in 1842, while Irish statesman Daniel O’Connell killed a duel opponent in 1815.

It survived into modern times – albeit with a few Health and Safety tweaks

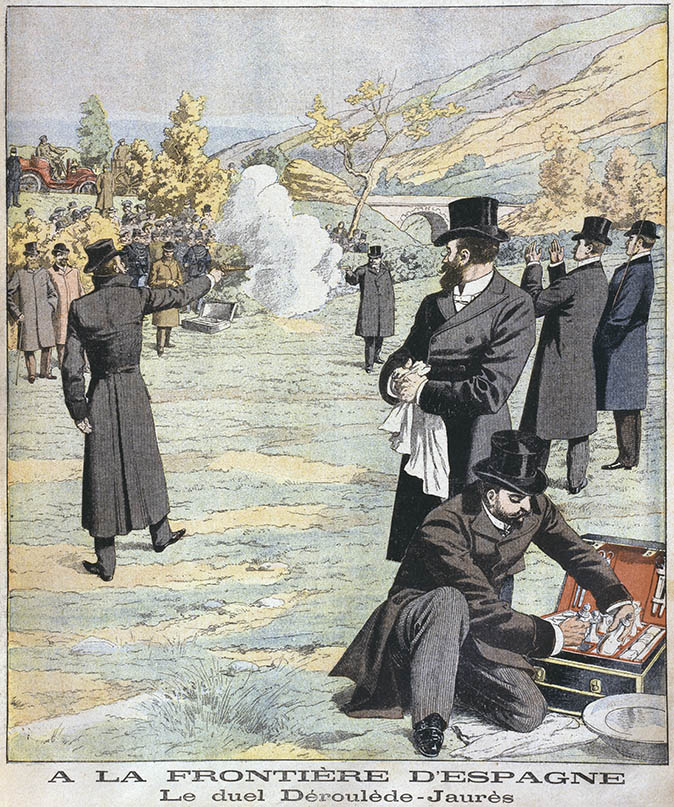

Duelling fell out of favour in Britain in the 19th century, with the last fatal meeting in 1852, but continued as a sport in France. Opponents in padded clothing and helmets used wax bullets, a practice that gained favour in America.

It was once an Olympic sport

The modern Olympic Games once featured ‘duelling pistol’ events with military revolvers and, in 1906, a quasi-Olympics called the Intercalated Games included marksmanship with real duelling pistols at 20m and 30m. The targets were dummies dressed in frock coats with bullseyes pinned at chest level.

Duels were sometimes mere gestures – but not always

The 7th Earl of Cardigan, soldier, fine horseman and shot, called out Capt Harvey Tuckett, in 1841, for publishing an account of a mess incident involving a black bottle of porter and shot him with a duelling pistol with a rifled barrel and hair trigger; both features considered unsporting.

Arraigned for wounding, Cardigan demanded to be tried by his peers. Queen Victoria let it be known she hoped he would ‘get off easily’ and he was acquitted on a technicality.

Cardigan had previously offered to duel with a Capt Johnstone, whose wife he had romanced, but Johnstone declared that he had given him satisfaction by taking on ‘the most damned bad-tempered and extravagant bitch in the kingdom’.

If you were good enough, you need never be challenged

Horatio Ross, named after his godfather Lord Nelson, was formidable in the field (he marked his 82nd birthday by shooting 82 consecutive grouse) and a top pistol shot, holing playing cards at 40 yards and winning bets by shooting swallows on the wing. His reputation ensured that Ross was never challenged.

But his reputation went even further, helping to save others from peril. On one occasion at a hunt dinner, one guest felt slighted by a fellow diner’s comments and swore that, if he knew who it was, he would horsewhip him. Told that it was ‘that pistol-shooting fellow Ross’, he melted away.

Ross personified the role of the second in dissuading a would-be combatant. He mediated on 16 occasions, with not a shot fired.

The pen is (sometimes) mightier than the duelling pistol

Mark Twain was challenged to a duel in 1864, but his opponent withdrew after hearing tales (all entirely bogus) of Twain’s prowess with a pistol.

Not all men of letters have been quite so adept at getting out of harm’s way: Russian literary giant Alexander Pushkin, a serial duellist, died in 1837 during his 29th encounter.

It wasn’t always pistols at 12 paces…

Two Frenchmen agreed to duel from balloons over Paris in 1808, one plummeting to his death after his envelope was punctured. Other recorded duels included a pair of duellists in 1842 – again, Frenchmen – by throwing billiard balls.

…and sometimes it’s been even stranger

In 1865, scientist and politician Rudolf Virchow was challenged to a duel over Prussian navy funding by the president, Otto von Bismarck. Almost unbelievably, sausage consumption was chosen over weapons – one of the bangers being laced with the Trichinella spiralis parasite. Bismarck had to choose which to eat, but withdrew his challenge.

Even the angriest and most talented duellists could get manoeuvred out of a killing

Probably the most flamboyant sportsman of the era was ‘Squire’ George Osbaldeston, a Yorkshire landowner, hard cross-country and race rider, pugilist, inveterate gambler and remarkable shot whose recorded flintlock achievements included 100 pheasants with 100 shots, 97 grouse with 97 shots and 20 brace of partridge with 40 shots. ‘And he was a dead shot with a duelling pistol, for he put 10 shots on the ace of diamonds at 30ft,’ wrote the editor of The Field in an introduction to Osbaldeston’s autobiography, discovered in his papers and published in 1926.

‘I do not wonder that most people were carefully polite to a plucky little customer who kept his temper better than most, but could either knock you down out of hand or put a bullet through your head next morning.’

Osbaldeston challenged Lord George Bentinck over his refusal to honour a 200-guinea bet, Bentinck claiming that the Squire had misrepresented the provenance of his horse Rush and had pulled the animal in a previous race to secure a light handicap for a big 1835 race. Osbaldeston’s request for the money was ‘damned robbery’, declared Bentinck.

Osbaldeston’s associates perceived him to be in the wrong and, the night before the 6am Wormwood Scrubs confrontation, a friend spent hours trying to mollify him, to no effect. In the event, the umpire fumbled the loading and Osbaldeston was convinced by the light recoil that his pistol was not loaded. If so, Bentinck’s pistol also carried a blank charge. No blood was spilled and the pair reconciled.

Curious Questions: Why do the British drive on the left?

The rest of Europe drives on the right, so why do the British drive on the left? Martin Fone, author

Credit: Rex

Curious Questions: Why do we still use the QWERTY keyboard?

The strange layout of keyboards in the Anglophone world is as bafflingly illogical. Martin Fone, author of 'Fifty Curious Questions',

Curious Questions: Do you get wetter running or walking in the rain?

Does running in the rain get you out of it quicker? Or do you just run into more water more

Credit: Alamy

Curious Questions: Do carrots really help you see in the dark?

We've all been given the familiar advice by parents anxious to get us eating our vegetables, but is there any

The 18th-century duelling pistols which ended up in the hands of a notorious British spy

A pair of duelling pistols up for auction hold a fascinating history, having once been owned by a notorious British

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.