Curious Questions: Was Captain Webb the first to swim the channel?

Captain Matthew Webb was famously the first man to successfully swim the English Channel — or was he? Martin Fone investigates.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Like Everest, it presents an irresistible challenge to the adventurous, simply because, to echo George Mallory, it’s there. At its narrowest point — between Shakespeare’s Beach at Dover and Cap Gris Nez, a headland between Calais and Boulogne — the English Channel might just be 18.2 nautical miles wide, but it forms a formidable barrier that tests the endurance, skill, and enterprise of all but a select band of long-distance swimmers.

These days the favoured starting point is Abbot’s Cliff beach on the south side of Samphire Hoe, about two kilometres from Dover, making it a slightly longer swim, the starting time usually an hour either side of high tide. Permission has to be sought from either the Channel Swimming Association or the Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation, while the French authorities’ marked reluctance to sanction swims means that crossings from France to England are almost a thing of the past.

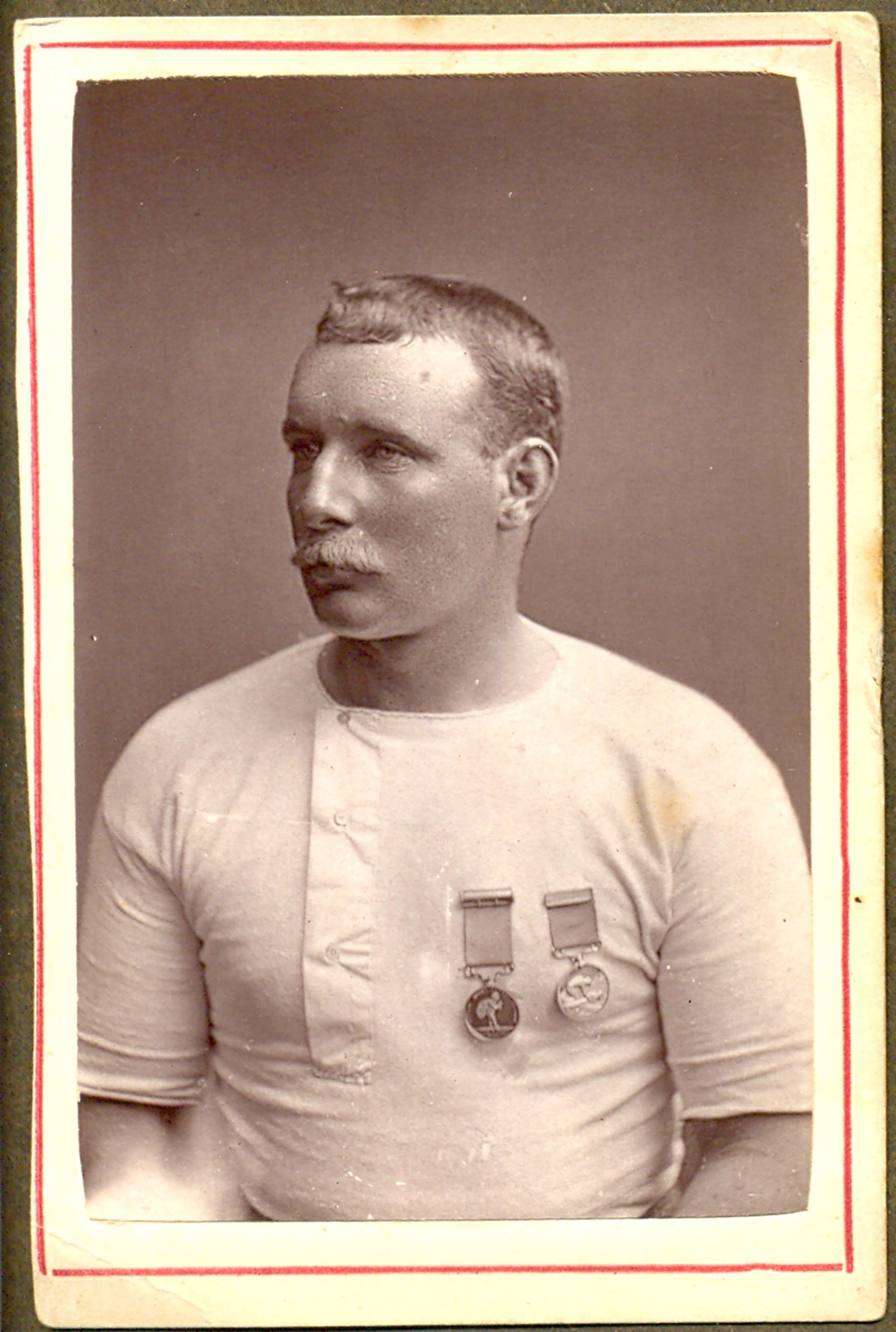

Despite all the hurdles and challenges, to date there have been 4,133 successful Channel swims, with 1,881 swimmers completing 2,428 solo swims, plus another 8,215 swimmers who have taken part in relay swims and special category swims. The first of these heroic swimmers was, famously, Captain Matthew Webb — though whether he was the first to traverse the channel without a boat isn't quite as clear-cut as it may seem, as we'll see later.

Endurance swimming had become popular in the 1870s and after reading of an unsuccessful attempt to cross the Channel, Webb, a strong swimmer, decided to try his luck. After some acclimatisation in the cold waters of the southern English coast, he made his first attempt on August 12, 1875. Webb didn’t succeed, being beaten by the high winds and adverse weather conditions he experienced.

Undaunted, wearing a red silken swimming costume and his body smothered in porpoise oil, he tried again twelve days later, swimming his finest breaststroke while being followed by three boats, supplying him with brandy, coffee, and beef tea to fortify him against the jellyfish stings and tangled patches of seaweed he encountered.

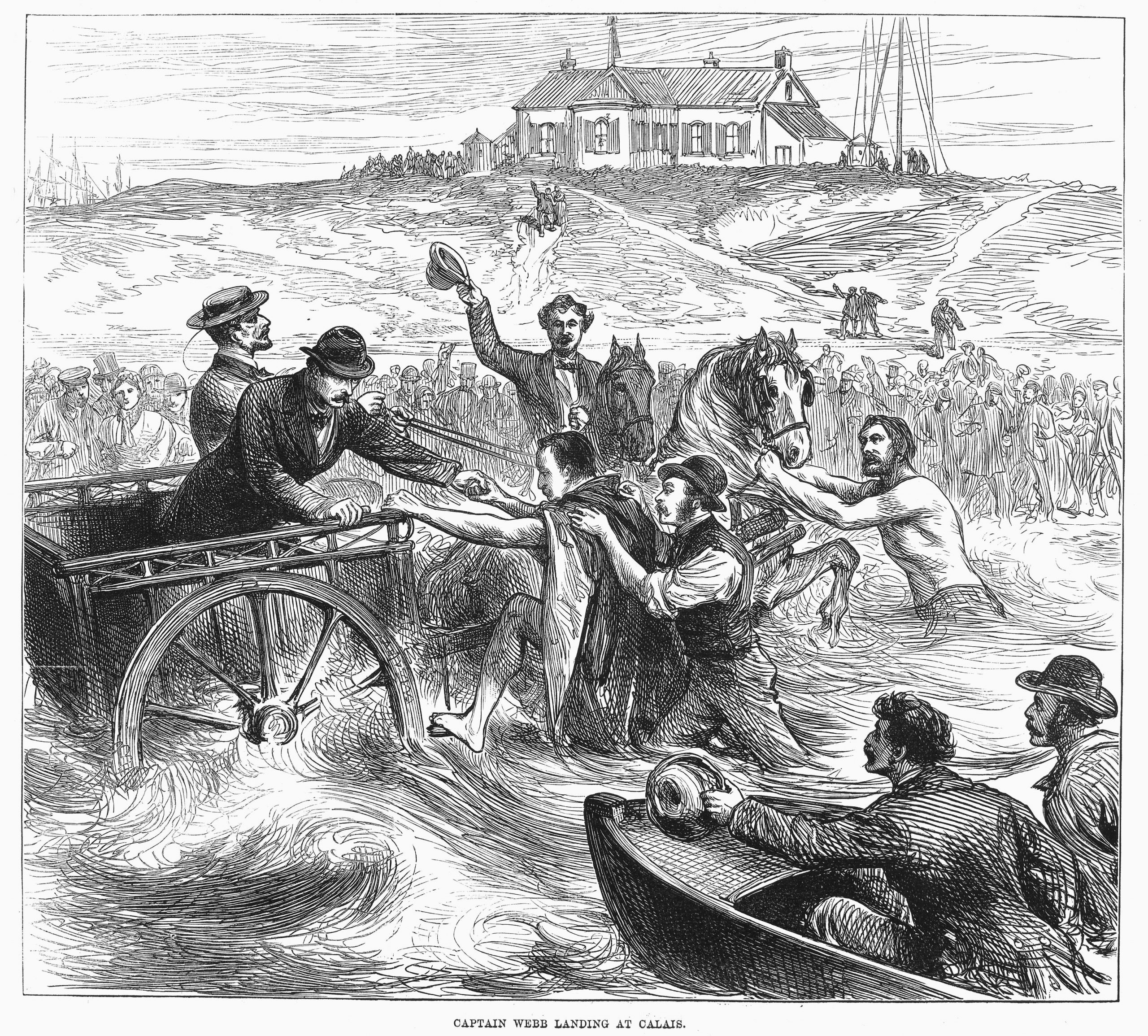

He very nearly didn’t make it. Eight miles short of Cap Gris Nez a change in tide forced him to swim for five hours along the French coast, waiting for it to abate. Eventually, at 10.41 am on August 25, 1875, Webb clambered wearily on to the shore, having swum the equivalent of 39 miles, mostly against the tide, in 21 hours and forty-five minutes.

News of his achievement spread around the world. The Daily Telegraph proclaimed the Captain to be the best-known man in the world; the mayor of Dover opined that no one would ever repeat the feat; and so enthusiastic was the cheering throng that greeted him at Wellington station on his return to his native Shropshire that a section of the crowd uncoupled the horses that were to convey him on to Ironbridge and pulled him along themselves. At Dawley he received ‘the homage of the town of his birth’ and was paraded down the High Street.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Now wealthy and an international celebrity, Webb was not content to rest on his laurels, a decision that was to cost him his life. On July 24, 1883, he attempted to swim down the Whirlpool Rapids at the Niagara, just downstream from the Falls.

Within ten minutes of entering the water, he was dead, having been sucked into one of the huge whirlpools. His body was recovered four days later, with an autopsy determining that he hadn't even had time to drown: Capt Webb's cause of death was recorded as 'crushing' due to the sheer weight of water on him.

In 1909 Webb’s older brother, Thomas, unveiled a memorial to him in Dawley which bore the legend ‘Nothing great is easy’. There are other memorials to him elsewhere as well, from stained glass images to a bust in Dover. There's even a stone commemorating his achievement in Calais.

But was Webb really the first? That rather depends on how you define ‘swimming’, as the story of Paul Boyton shows.

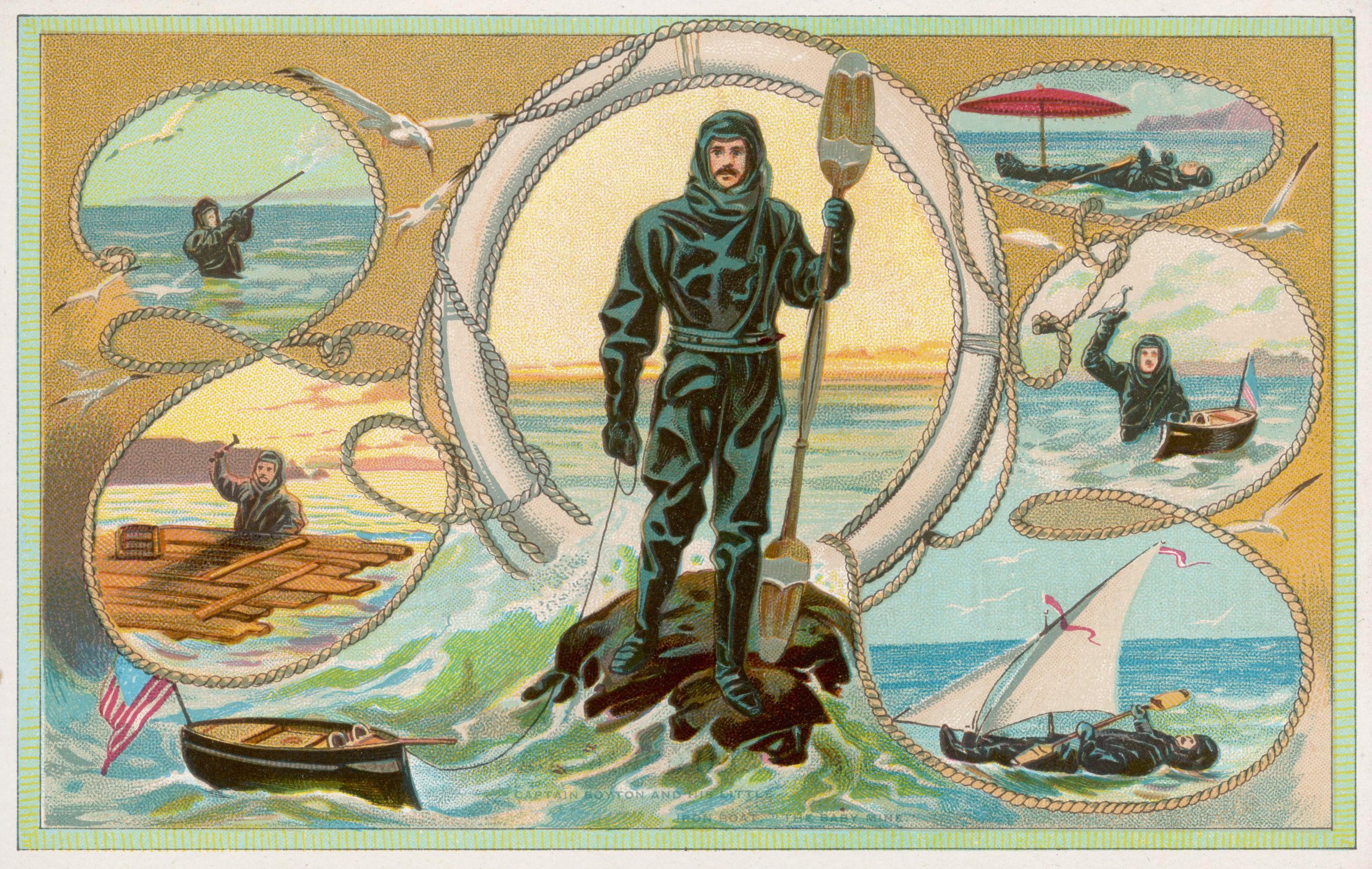

Boyton was born in County Kildare in 1848 and shortly afterwards was taken by his family to the States. He grew into a strong swimmer with a sense of adventure, spending his youth in the navy and then establishing the United States Life-Saving Service, the forerunner of their Coastguards. A meeting with Clark S Merriman, who had recently invented an inflatable, rubber life-preserving suit, presented him with a challenge that combined his interest in lifesaving, his natural showmanship and love of derring-do; to put the suit through its paces.

Unable to resist the lure of the English Channel, he decided that crossing it would prove his mettle as a long-distance swimmer as well as demonstrating the seaworthiness of the suit. Dubbed the Fearless Frogman, his penchant for publicity ensured that he attracted press attention, The Times noting that his India rubber suit could be inflated by some tubes, allowing the wearer to float and propel themselves with the aid of a paddle. It was also airtight and waterproof.

On April 10, 1875, onlookers at Dover harbour were treated to the strange sight of Boyton wearing his suit over blue serge undergarments and woollen stockings. On each foot was a socket into which a small mast was placed which allowed for a sail, the size of a large handkerchief, to be hoisted and controlled, using lanyards attached to the suit. A foghorn around his neck, a brandy flask in a waistcoat pocket, a large knife, a double-bladed oar for propulsion, and a packet of letters safely secreted inside, ‘the Boyton mail for the Continent’, completed his ensemble.

Followed by Rambler, a steam tug full of reporters, Boyton set out, lying on his back and using his oar ‘skilfully’ for propulsion, consuming a bizarre diet of beaten eggs, cherry brandy and smoking a cigar along the way. The Channel, though, was not easily beaten. After fifteen hours in the sea and covering 50 miles, the weather worsened to such an extent that the French pilot feared for the swimmer’s safety, threatening to leave them when night fell, if Boyton did not abandon the attempt.

Boyton reluctantly concurred but went to extraordinary lengths to prove it was not his decision, requiring the reporters present to sign a declaration to that effect and, when onshore, obtaining a certificate from a doctor stating that he was medically fit to have continued. The Fearless Frogman may have demonstrated the seaworthiness of Merriman’s suit, but he was not finished with the Channel.

At 3am on June 28, 1875, Boyton set out from Cap Gris Nez, again dressed in his inflatable bathing suit. There was important addition, a small screw propeller was fixed with hoops to his torso and thighs which enabled him, while lying prone, to propel himself. It might just have been one of those ideas that sounded good on paper but just proved impractical, as there is no reference to it in reports of his progress. He also changed his diet, fortified along the way with three meals consisting of green tea and beef sandwiches.

The weather was kind to him, the only alarum being an encounter with a porpoise four miles off Dover. At 2am the following morning he walked ashore at Faro Bay in Kent and was taken by steamer to Folkestone, where he was ‘enthusiastically received’, having completed his crossing almost two months before Webb. Jules Verne featured his suit in Tribulations of a Chinaman in China (1879).

After a career of endurance swimming Boyton settled down and opened Chicago’s first fixed amusement park in 1894 and the Sea Lion Park on Coney Island the following year, and, unlike Webb, enjoyed a long life before dying in 1924.

For a swim to be sanctioned by the Channel Swimming Association, the swimmer must be unaided and wear only one swimming garment. Clearly, Captain Webb met the modern criteria and was the first to swim the channel unaided, but, undeniably, Paul Boyton got there first, with a little help from Merriman’s suit, an oar and, possibly, a propeller.

The British rivers being made officially clean enough for wild swimming

2020 saw a disturbing rise in sewage being dumped in British rivers, but new schemes are popping up to clean

10 great places around the world to base yourself for overseas adventures, from wild swimming to, er, playing boules

If you're looking beyond the pandemic and are thinking of a holiday home overseas, Carla Passino picks out 10 places

Feargal Sharkey: From Top of the Pops to crusading for Britain's rivers

Feargal Sharkey, one of the most recognisable pop voices of the 1970s and 1980s, talks to Country Life about his

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.