Curious questions: Why do golf balls have dimples? And why are tennis balls furry?

As the weather picks up and tennis takes over the silver screen, millions of us are starting to thinking about dusting off our golf clubs and tennis rackets. Which begs the question, why aren't the balls we use for tennis and golf perfectly smooth?

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

According to a survey conducted for Our Sporting Life, more than one in 20 of those aged 16 or over in the UK, planned to play, at least once a month in 2024, what non-enthusiasts call ‘a good walk spoiled’.

Golf requires a combination of skill, strength, and accuracy to hit a ball over several hundred yards and finish by sinking it into a hole 4.25in in diameter. Counterintuitively, it is one of the few sports where the less skillful the player is, the longer the game lasts.

Golf balls have come a long way since the modern game, played over 18 holes, was developed in Scotland in the late Middle Ages. While the first might have been wooden, by the start of the 16th century golfers were using a hand-sewn, round leather ball filled with cow’s hair or straw, initially imported from the Netherlands. Known as hairy balls, they were later manufactured in Scotland as a dispute between the cordiners of Cannongate in Edinburgh and the ‘cordiners or gouff ball makers of North Leith’ in 1554 reveals.

In the early 17th century a rival emerged — the featherie, stuffed with goose or chicken feathers. The feathers and leather would be shaped when wet and allowed to dry, when the leather would shrink and the feathers expand to produce a hard ball. It would then be painted and adorned with the maker’s mark. While harder than the hairy, featheries were difficult to make perfectly round, had a tendency to lose distance when wet, and often split open upon impact.

A hand-hammered Gutta-Percha golf ball made in the 19th century by Allan Robertson.

The game changer came in 1848 with the development of the Gutta-Percha ball or Gutty. Made from the dried sap of the Malaysian Sapodilla tree which had a rubber-like quality, it could be formed into a sphere when heated. And, in 1898, another new type of golf ball was developed by Coburn Haskell with a thin outer shell made of balata sap covering a liquid-filled or solid core, around which was wound a layer of rubber thread. The rubber Haskell golf ball, the standard in use today, had arrived.

Despite the improvements in ball technology, golfers still found that used balls, with their marks and indentations, travelled further than new balls, a point that piqued the interest of an English engineer and manufacturer, William Taylor. After a series of experiments to determine which surface formation gave the best flight, he hit upon a pattern featuring regularly spaced concave dimples on the ball’s surface. He patented the design in 1905 which, together with the harder Haskell, revolutionised the game.

Dimples disturb the air around the ball, creating a thin layer of air that clings to its surface, decreasing drag, and allowing it to travel more smoothly through the air more quickly and for longer distances. They also encourage the ball to spin, which creates lift. More dimples can create a softer flight path, ideal for those seeking control and precision, while fewer dimples reduce spin and allow for longer drives. Importantly in our climate, dimples stabilise the ball in windy conditions.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

While the rules of golf determine the size and weight of golf balls, there are no restrictions on the number of dimples. Most have between three hundred and 500, the average being 336, a number which seems to optimise lift and control. The record number, though, is 1,070 dimples — 414 larger ones in four different sizes and 656 the size of pinheads.

The first balls used in the modern version of lawn tennis in the 1870s were initially imported from Germany, air-filled and made from vulcanised rubber. By 1882, they were being covered with stout flannel stitched to a solid rubber core and then later they had a hollow core with gas pressurising the interior. The balls in use today, made by compression moulding a rubber compound into two separate half-shells, which are then pressed together to make the core, must be between 2.575 and 2.7in in diameter and weigh between 56 and 59g.

'Without a nap, a tennis ball travels much more quickly and further... It is almost impossible for the opponent to react to the shot'

The most important and expensive component of a tennis ball is its fuzzy, furry coating, known as the nap. Made from wool, nylon, and cotton, it is cut out into a dumbbell shape, two pieces of which are glued on to the ball, giving it its distinctive curvy seams.

The nap makes the game playable. A smooth ball offers little friction between its surface and the surrounding air, so it travels through the air quickly. A rough surface, though, increases the friction between itself and the surrounding air, creating turbulent swirls behind it which, in turn, forms areas of low pressure. The difference in pressure between the front and the back of the ball causes it to slow down, an effect known as skin friction drag. The sucking action of the low pressure area also curves the ball’s trajectory and imparts spin.

Without a nap a tennis ball travels much more quickly and further, making it difficult to control and keep within the perimeters of the court. It is almost impossible for the opponent to react to the shot, increasing the risk of injury and reducing the game, at best, to a succession of unanswered serves.

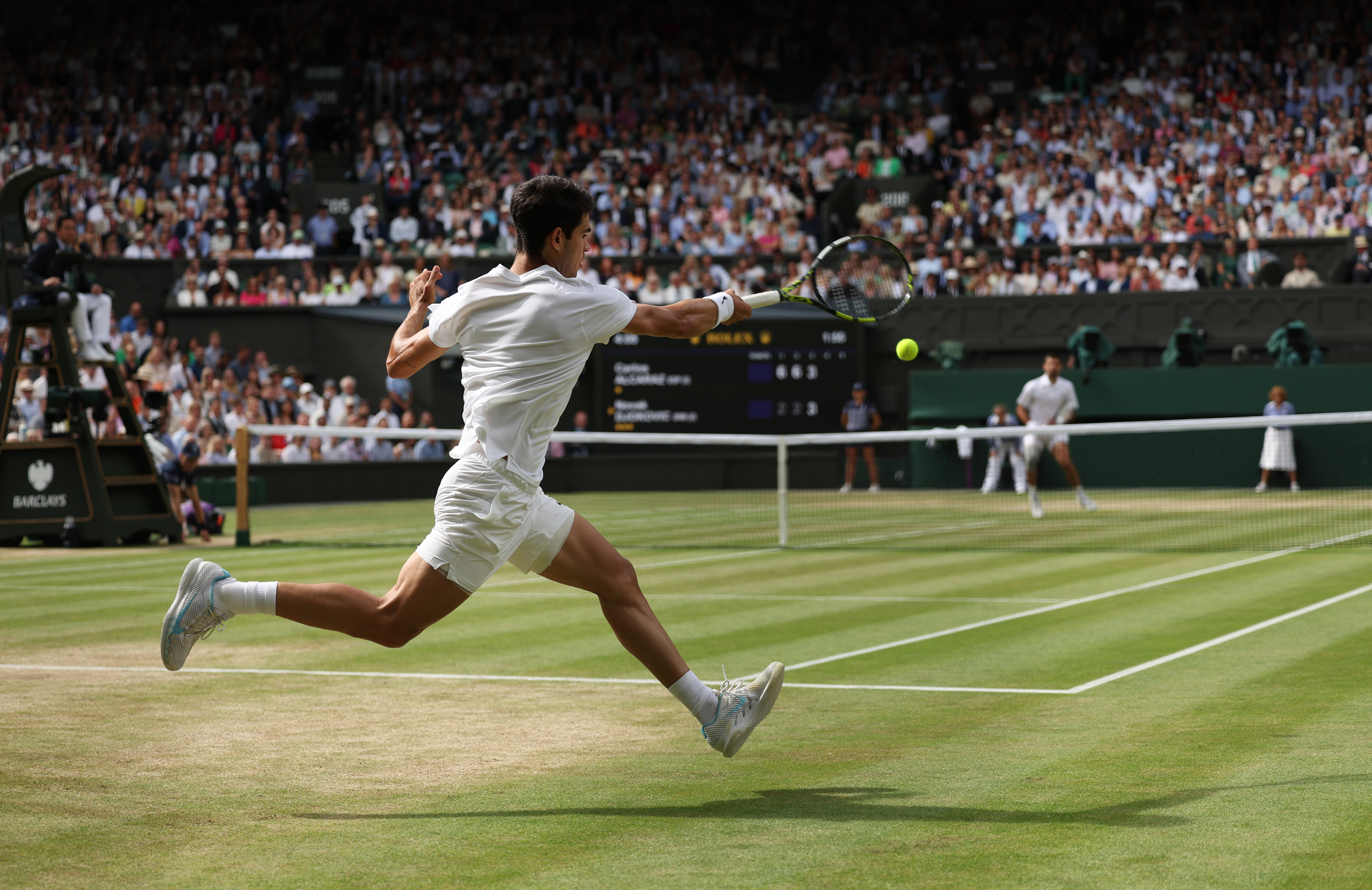

The increased drag produced by the nap, though, slows the ball down to around a third of the speed that it left the server’s racket. While the loss of speed, further reduced when it bounces off the ground, increases the likelihood of the opponent returning the serve, it offers the server greater control. Experienced players use the drag force to make the ball spin in different directions using forehand and backhand shots which send their opponents scampering around the court.

The force with which a racquet hits a tennis ball soon damages the nap, which then impacts its performance and the players’ ability to control it. That is why professional players scrutinise the ball they pull out of their pocket before serving and why the umpire’s call of ‘new balls please’ frequently punctuates a match.

And why are they yellow? To increase their visibility on television, following a suggestion made in 1967 by Sir David Attenborough after the first colour transmission from Wimbledon and adopted in 1972. Curiously, though, Wimbledon retained white balls until 1986.

So, in conclusion, the distinctive coverings of golf and tennis balls help to improve the players’ control and make for better games.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.