In Focus: The trench cello which brought the joy of music to the First World War

The men who spent years in the trenches of France and Belgium found all manner of ways to bring a touch of joy and culture into their lives – not least with the portable, collapsible cello which 2nd lieutenant Harold Triggs of the Royal Sussex took into battle in 1914. The instrument works beautifully today, as Claire Jackson reports.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Debussy’s haunting cello sonata, composed in 1915, is at once plaintive and ecstatic in Steven Isserlis’s hands. The work, played on the Marquis de Corberon Stradivarius of 1726 – on loan from the Royal Academy of Music – produces a multi-faceted tone and opens the ‘The Cello in Wartime’, a beautiful, thought-provoking collection of pieces written during the First World War era.

Then, the cello’s voice changes: we hear ‘The Swan’ from Saint-Saëns’s Carnival of the Animals. The tone is softer, a little shallower, perhaps, but just as beautiful. Mr Isserlis has swapped his Stradivarius for the ‘trench cello’, an instrument that resonates with the emotions weaving through this repertoire, and which survives to this day from the First World War.

The trench cello belonged to Harold Triggs, a keen amateur cellist in the Royal Sussex Regiment. It was one of a several similar ‘travelling’ cellos that were intended to be more portable than their counterparts proper for travels presumably more pleasurable than a stint in the trenches, which is where Triggs and his cello – a 'holiday cello' made by W.E. Hill and Sons around 1900 – found themselves.

Triggs wasn’t the only musician to perform in the trenches: the Australian composer F. S. Kelly, who was killed, detailed the music he played during trench concerts in his diaries, accounts Mr Isserlis used to inform his programming.

‘I wanted to play things that Triggs might have played during the war,’ he explains.

‘Alongside the Saint-Saëns, I chose a hymn, a popular song and God Save the King. I wasn’t sure I could do The Swan, because there are a couple of notes that don’t speak on the trench cello, but, in fact, that’s one of the pieces that people talk about the most.’

It’s unsurprising that a couple of notes are problematic on the trench cello, because the instrument is rather rudimentary – it can be assembled in less than five minutes. The body is rectangular, with a removable neck that’s secured with a normal mortise joint, fixed to a button at the top of the back with a brass bolt. The fingerboard slides into place on the neck and the top nut is added, as are the endpin holder, tailpiece, bridge and strings.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The back slides out so that all the fixtures and fittings can be placed inside the box, including the bow; when it’s packed up, the cello looks just like an ammunitions box, the item soldiers often used to form instruments.

‘With conventional cellos, you can move the sound post around or adjust the bridge,’ says Mr Isserlis.

‘This is essentially a box with some holes, but it sounds lovely.’

Mr Isserlis learned of the cello through his friend Charles Beare in 2014. Mr Beare, an expert in the field of fine antique stringed instruments and bows, is part of the historic family business J. & A. Beare that has served elite musicians and collectors since 1892.

‘I mentioned that we’d fished the cello out of storage and Steven was interested right away,’ remembers Mr Beare. Days later, the musician travelled to Mr Beare’s home in Kent to try it.

‘It took a few minutes to adjust my playing, but, after that, we connected,’ reports Mr Isserlis. Later that year the cellist played the instrument in a special Parliamentary Service of Remembrance in Westminster Abbey on Armistice Day to commemorate the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War. ‘It was a great moment for us all,’ reflects Mr Beare.

Although there are no current plans to perform with the trench cello in public, Mr Isserlis hopes to reconnect with his old friend for the centenary celebrations. In the meantime, it remains with Mr Beare, who’s writing a book about its history. He’s well placed for this, given that his firm has owned the cello since 1962.

‘Harold Triggs came to us and asked for £15, along with the assurance that it would have a home,’ he says, adding: ‘It’s been with us ever since.’ Mr Triggs died soon after, in 1964.

Mr Beare is reticent about putting a price on the trench cello. He knows of at least five portable cellos in existence, probably made ‘for holidays, cruise liners and the sorts of places where one didn’t want to make a lot of noise’, but none of these are known to have gone to the trenches. They probably don’t have the curious story behind them that this instrument does, either.

‘We don’t know a huge amount about Triggs, but we know that, towards the end of the war, he was captured by the Germans during a counterattack,’ explains Mr Beare.

‘He didn’t see the cello again until years later, in the late 1950s, when he was walking along the beach at Brighton and passed someone holding it!’

Hidden on the back is an inscription written in 1962 by war poet Edmund Blunden who, like Triggs, was an officer in the Royal Sussex. It recalls their time together at Ypres and expresses his pleasure at being reunited with the cello, almost 50 years after hearing it in the trenches. There’s also an invitation stuck to the instrument, which dates from 1916, when Triggs was summoned by the corps commander to play for the officers.

Mr Beare doesn’t have any plans to sell it, although, as he points out, ‘obviously no one comes to the shop and says “have you got a trench cello?”. I offered it to the Royal Sussex Regiment Museum, but that’s since closed down.’

For the time being, the trench cello remains where Triggs intended, although there’s no doubt the veteran would be pleased to see it loaned out to Mr Isserlis once in a while.

‘The Cello in Wartime’ album, which includes works by Bridge, Fauré, Novello, Parry and Webern, with pianist Connie Shih, is available via BIS Records or Amazon. Steven Isserlis’s new CD of Chopin and Schubert sonatas with pianist Dénes Várjon is out now on Hyperion.

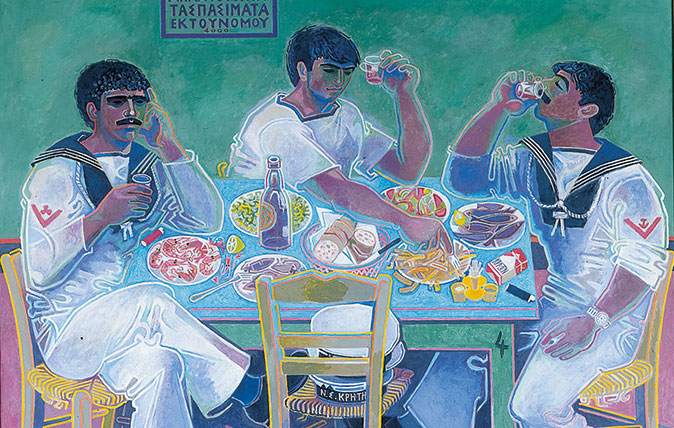

In Focus: The charmed life of Paddy Leigh Fermor and friends in Greece

The iconic writer Paddy Leigh Fermor and two of his friends in Greece – both artists, one a local man and

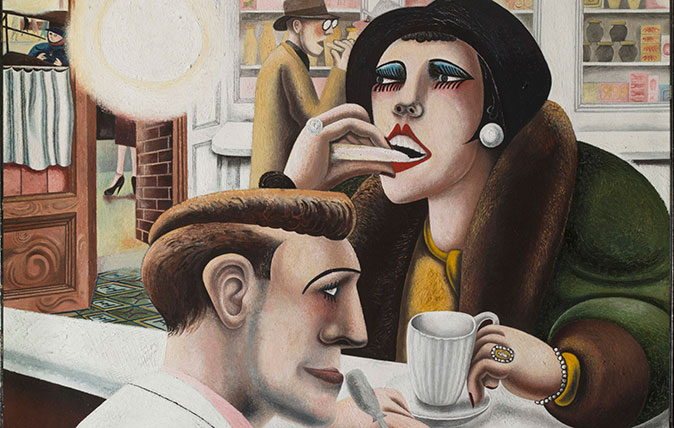

In Focus: The evocative, sensual masterpiece created in the wake of the First World War

Edward Burra was too young to have fought in the First World War, but his powerful oil painting The Snack

Credit: Alamy

In Focus: A grim masterpiece of the French painter who became the ultimate storyteller in paint

Laura Freeman examines the brilliance and bravado of Eugène Delacroix’s paintings – including an extraordinary recreation of one of the most

In Focus: The ancient roman temple which lay under London, undiscovered for over 17 centuries.

The temple of Mithras has been beautifully restored by Bloomburg SPACE and now sits under their Headquarters by Bank tube

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.