Interview: Bishop of London

Bishop Chartres is very much a champion of special tradition, finds Jeremy Musson. He has spent years resisting the closure of City churches and believes parishes can use them to engage with the wider community

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

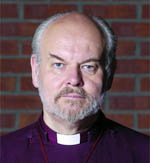

The Bishop of London since 1995, Richard Chartres is a striking figure. Tall and bearded, he has been mistaken for an Orthodox pat-riarch, although they are obliged to be monks and Bishop Chartres is married to Caroline, a journalist, and they have four children. He is very much a champion of a special tradition: 'I like the idea of the Church of England (C of E) rather than the idea of Anglicanism'. Brought up in Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, his parents were not active churchgoers, 'but religion was pretty inescapable in the 1950s although I wasn t confirmed until I was at Cambridge. I did a kind of Which? report on different traditions when I was a teenager. I'm amused to recall that I ran a mile from the warm welcomes and favoured the C of E because it left you alone. I became involved in chapel life while reading history at Trinity College.'

Theological college followed, but he felt he didn t fit in. 'It was the late 1960s, and those brought up in the tradition of the Church knew it was time for change, but I had just joined and didn t want any change.' He left and worked as an orders clerk for Sainsbury's and a teacher at the International School in Seville. 'I later went to theological college at Lincoln, and spent time at the Samaritan Centre just listening to people talking about lives so different from the ones I knew. I learnt that everybody is extraordinary if you get to know enough of their story.

'One of the things that opened me up spiritually was my brother Stephen, who was born severely mentally handicapped and died in his twenties, but always had an enormous capacity for joy and for love. I do feel constantly called to make sense of it all beyond the mystery of human life, and I find it in the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.' In 1995, Bishop Chartres famously resisted the closure of City churches. 'In central London, we have had to ask for some of the churches back that we d leased out for other purposes. With imagination and extended use (but not alternative use), it's possible to change things. Whenever I go into a church, I find myself interrogating its story. When St Ethelburga's was damaged by a bomb, we were inspired to refound it as a centre for reconciliation and peace. This was partly a response to its fate at the hands of terrorists whose conflict was, in part, defined by religious conflict but also the church's longer history.

'When the Sultan of Aceh wrote to Elizabeth I, the only person in London who could translate was the rector of St Ethelburga's. I also identified that a 19th-century rector, J. M. Rodwell, had translated the Koran. People who have a sense of destiny without a sense of history are very dangerous but a person with only a sense of history is a rather dull dog.' He believes that each church 'has its own story' and this can help inform its future. 'At St Stephen s Walbrook, where Chad Varah founded the Samaritans, we have set up an internet church to serve the City office workers.' Bishop Chartres is also the chair of the Church of England's Cathedral and Church Buildings Division, responsible for the care and future of all parish churches: 'Some 45% of Grade I-listed buildings in England are cared for by the Church of England, but in France, all pre-1904 churches are in the care of the State, and Germany and Scandinavia have a church tax. English Heritage is supportive and funds 6% of repairs.

'I do believe parishes could use churches to engage with the wider community, without abandoning prior use as a church. Think about how many billions it would take to construct a network of centres serving communities like the one that already exists with the parish churches of England. So much good has been done throughout history through these churches. The Church of England has a non-sectarian gene and we really are there to help all the community, not just ourselves.'

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.