William Shakespeare: The original Nature boy

William Shakespeare wasn’t only the greatest playwright of our history, he was an avid ornithophile, a green man and a master of transposing the true power of Nature onto the page, says John Lewis-Stempel.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Shakespeare was in love with Nature. When Dr Johnson praised the Bard as ‘the poet of nature’, he meant Shakespeare’s penetration of the human condition, the vaulting ambition of Macbeth and the paranoid insecurity of Hamlet, but the honorific might equally be applied to Shakespeare’s feeling for natural history. After all, this is the playwright who, in Measure for Measure, agonised for the smallest of creatures:

And the poor beetle that we tread upon, In corporal sufferance finds a pang as great As when a giant dies.

Nature was his inspiration, because he was born a Nature boy, the grandson of farmers, and he grew up in Stratford-upon-Avon, then a small country town. His knowledge of our wild fauna and flora, from ‘the quarrelous Weasel’ (Cymbeline, Act III, Scene 4) to Romeo’s recommendation of plantain as healing herb (Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene 2), is so marked in his apt metaphors, similes and descriptions that it can only have come from personal observation as he played and rambled in the fields, woods and streams of the Midlands.

Shakespeare understood insect metamorphosis (Love’s Labour’s Lost, Act V, Scene 2), and the partiality evinced by serpents for basking in the sun:

It is the bright day that brings forth the adder; And that craves wary walking.

He recognised the functions of various types of larvae, be they silkmoth cocoons (Othello, Act III, Scene 4) or carrion maggots (Hamlet, Act II, Scene 2). And is there a better picture of the interior of a hive than in Henry V?

For so work the honey bees, Creatures that, by a rule in nature, teach The act of order to a peopled kingdom. They have a king, and officers of sorts: Where some, like magistrates, correct at home; Others, like merchants, venture trade abroad; Others, like soldiers, armed in their stings, Make boot upon the summer’s velvet buds; Which pillage they with merry march bring home…

The young Will, we may surmise, had a hands-on closeness to Nature. Legend accords him the role of deer-robber from the estate of Sir Thomas Lucy. So sure is Shakespeare’s depiction of falconry, a popular Elizabethan sport, that, in the words of the pre-eminent Shakespearian scholar Caroline Spurgeon, ‘there is evidence of personal experience’. Who but a falconer could write of Macbeth’s guilty anguish: ‘Come seeling night, scarf up the tender eye of pitiful day.’ ‘Seeling’ is the falconer’s term for covering the eyes of a bird to keep her quiet on the perch or on the gloved fist until it’s time to fly.

When we join the Bard, whether we are going to ‘a bank where the wild thyme blows/ Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows’ or down to the sea ‘whose rocky shore beats back the envious siege of watery Neptune’, we walk with a naturalist. His audiences at The Globe would have gleaned even more than we do from his works, which are rooted in a reading of Genesis that placed animals alongside humans in a greater vision of belonging. For Elizabethans, the boundary between man and animal was thin and porous; Shakespeare’s most famous stage direction, ‘Exit, pursued by a bear’, humanises the fur-clad creature. Shakespeare’s teeming Nature references came to be regarded post-Enlightenment as abstract theatrical devices, whereas for the crowd at The Globe they added a dimension of sensory comprehension. Of feeling.

If Shakespeare had a predilection for Nature, his relationship with it was nonetheless not a nostalgic one. Throughout his oeuvre, he depicts the countryside as it truly is: contradictory and complicated. The Bard’s rural landscape in As You Like It, the Forest of Arden, is idyllic, with highborns playing at being wooing, fluting shepherds and shepherdesses. It is a morally pure ‘golden world’. Duke Frederick on simply coming to ‘the skirts of this wild wood’ and ‘meeting with an old religious man’ (Act V, Scene 4) is reformed from his malfeasance. However, the same dreamy, pastoral glades contain a rampaging lioness, hunted deer and the fool Touchstone injecting the empty-belly realty of shepherding. The woods in A Midsummer Night’s Dream are emphatically magical, ruled by fairie monarchs and replete with the mischievous pranks of Puck. Yet, who, on entering a wood on Midsummer’s Eve, has not found wonder?

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Nature in King Lear, meanwhile, is neither pastoral nor otherworldly. It is an omnipotent, oppressive storm-lashed wilderness, into which the King is turned out by his daughters. Lear’s mental state erodes before our eyes as he drifts around the desolate heath under ‘wrathful skies’ and

Such sheets of fire, such bursts of horrid thunder, Such groans of roaring wind and rain, I never Remember to have heard: man’s nature cannot carry The affliction nor the fear.

King Lear’s health is the cruel reminder that Nature can exacerbate, as well as soothe, human agonies and that we poor humans are numberless ant-like things signifying nothing. Even less cheery is Macbeth and the meeting of the Weird Sisters on ‘a blasted heath’ in the Scottish wilds. Although the supernatural in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is nominally benevolent, in Macbeth, it is downright dangerous. However, the take-away from both plays is that Shakespeare’s Nature contains a spiritual element. You might even say that he worshipped Nature, as well as loved it. You could even charge him with pantheism.

Certainly, the boy from Stratford adored birds. Of all natural phenomena Shakespeare mentions, it is avia to which he refers most often. The plays and poems fly and wing with images derived from birds; 64 different types of birds can be found spread over 606 occurrences in the Bard’s writing. From osprey to turtle dove, to martlet and starling, the occupants of Shakespeare’s Aviary are tasked with dramatic purpose. Turmoil in the kingdom is announced when a lowly owl (Macbeth) brings down a powerful falcon (King Duncan).

’Tis unnatural, Even like the deed that’s done. On Tuesday last, A falcon, tow’ring in her pride of place, Was by a mousing owl hawk’d at and kill’d. (Macbeth — Act II, Scene 4)

A lark is used to mark time in one of the Bard’s most poignant scenes, when Romeo and Juliet are awakened in their marriage bed by birdsong. Juliet asks Romeo: ‘Wilt thou be gone? It is not yet near day. It was the nightingale, and not the lark, that pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear.’ Romeo, who is facing execution for killing Juliet’s cousin Tybalt, correctly identifies the morning bird as the lark and escapes out of the window before he is discovered by her family. Discerning the right species, lark or nightingale, was a matter of life and death. Romeo, like his creator, knew his birds.

Love of birds in ‘this blessed plot’ called Britain is very old, and dates back to the Anglo-Saxons. But it was cemented into our consciousness by the avia in the Bard’s plays, which are the foundation texts of British identity. To this day, we use Shakespearean bird idioms in everyday conversation. ‘At one fell swoop’ and ‘wild-goose chase’ both derive from the Nature-lover from Stratford.

In the eve of his career, Shakespeare paid for the right to commission a coat of arms for his family. Atop the arms, ‘tow’ring in her pride of place’, he installed a falcon. Of course he did.

Shakespeare the environmentalist

‘One touch of nature makes the whole world kin…’ (Troilus and Cressida, Act III, Scene 3). Was William Shakespeare the first Green? He wrote at the commencement of the Anthropocene (the era when humans fundamentally altered the ecosystem) and his plays worry away at the damage done to earth by nascent industry.

In Henry IV, Part I, a courtier finds it a ‘great pity’ that ‘this villainous saltpetre should be digg’d/Out of the bowels of the harmless earth’. New fuel-intensive industries such as iron-forging for Hamlet’s ‘brazen cannon’ made deforestation England’s first major environmental crisis.

Overfishing, the draining of wetland for agriculture and the fur trade are all critiqued and the period’s unusually volatile weather—the plays rip with tempests—is uncomfortably reminiscent of our own time. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the fairies note with alarm that ‘the seasons alter’, as we do, too.

However, Shakespeare offers salvation; characters tend to change for the better when in relationship with Nature, as Duke Senior recognises in the Arden Forest, where, away from the court, he:

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, Sermons in stones, and good in everything.

How Country life revealed the true face of Shakespeare [VIDEO]

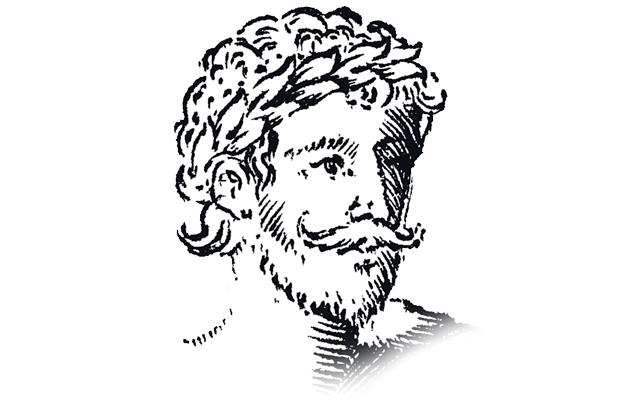

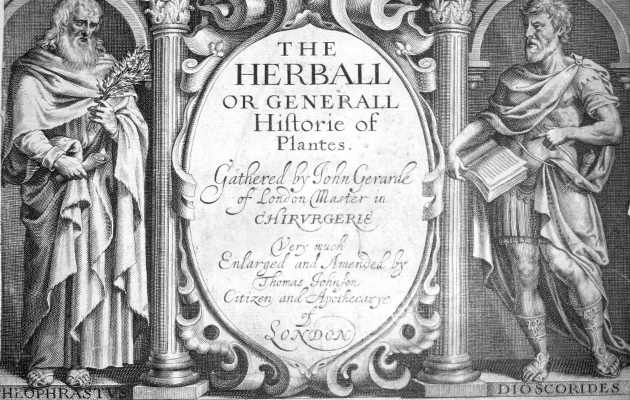

Country Life magazine reveals an astonishing new image of William Shakespeare, the first and only known demonstrably authentic portrait of

The true face of Shakespeare: Dioscorides and the Fourth Man

Mark Griffiths explains in depth why the Fourth Man is not Dioscorides.

The true face of Shakespeare: further evidence of its authenticity

Although a Harvard academic claims a 1749 book has proof that Shakespeare’s rebus in The Herball is a printer’s mark,

Why the fourth man can't be anybody but Shakespeare

A number of commenters have put forward theories of their own. But does the evidence stack up for them? Mark