Hartland Abbey: The beautiful Devon house behind which lies 1,500 years of history

David Robinson visits Hartland Abbey in Devon, a seat of Sir Hugh and Lady Stucley, starting from its nebulous medieval origins as an ancient religious site associated with the cult of St Nectan.

Marvellously situated in a tranquil valley along the rugged Atlantic coast of Devon, Hartland Abbey seems at first glance like a Regency house in the Gothic style so beloved by the late-Georgian squirearchy of Britain. Behind its crenellated façade and pointed windows, however, there is a much deeper history, one which extends all the way back to the emergence of Christianity in western Britain.

In fact, at nearby Stoke — the site of Hartland’s medieval parish church (Fig 4) — there is evidence for a small early religious site, focused around the cult and relics of a local hermit, Nectan. By the time of the Norman Conquest, this had emerged as a major English ‘minster’, served by a body of priests, or ‘secular’ canons.

In the 1160s, the old-established community was disbanded, to be replaced by ‘regular’ canons, the term relating to their observance of the quasi-monastic rule attributed in the Middle Ages to St Augustine of Hippo (d. 430). Their new abbey, dedicated to St Nectan, was built on the very spot now occupied by the Georgian house (Fig 1).

In seeking to unpick the detail in this story, our starting point is a 14th-century manuscript, now housed in the Ducal Museum at Gotha in Germany. Among the folios are rare hagiographical texts, several of which are of West Country provenance, notably the Lives of St Petroc, St Piran and St Rumon. It is, nevertheless, the inclusion of the Life of St Nectan that adds weight to the suggestion that this important manuscript may actually have been assembled at Hartland Abbey.

The activities of Nectan, an early British missionary saint, can possibly be traced to the beginning of the 6th century. According to the Life, he was one of many children born to legendary Welsh king Brychan. Being a ‘steadfast lover of God’, Nectan left his family and went in search of a life of eremitical prayer and contemplation. He boarded a small boat on the south Wales coast and navigated the perilous voyage across the Bristol Channel alone.

Having made land somewhere close to Hartland Point, with God’s guidance Nectan found his way to ‘a valley of delightful beauty, with woods rising there in abundance’, a description that remains perfectly apt for the topography in which Hartland Abbey sits today. It seems, however, that Nectan was not drawn to the valley bottom, with its gently flowing Abbey River, but chose instead to dwell on the neighbouring ridge at Stoke, overlooking the future site of the medieval abbey.

It was at Stoke that Nectan at last found the solitude he craved. Here, he built a hut from the trees, foraged for food and drank from a nearby fountain, or well, of ‘never-failing water’. Many of Nectan’s brothers and sisters — who had followed him to the South-West — likewise promoted the Christian mission. It was their tradition to assemble at his hut on December 31 each year.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As news of Nectan’s holiness spread, and in return for a certain kindness, he was given two cows by a pious local man. When the cows were stolen, Nectan tracked the brigands down and attempted to convert them to the Christian faith. Instead, they ruthlessly beheaded him. Miraculously, Nectan then picked up his severed head and carried it for half a mile back to the well near his hut. One of the thieves repented and buried him within the hut.

Whatever the truth of this narrative, a cult of St Nectan developed around the site of the martyr’s hut and well. In due course, a church of some form must have been built over the body. Indeed, the hagiography in the Gotha manuscript proceeds to recount the discovery of the saint’s relics in the early 11th century, by Brictric, a priest of Nectan’s church. At first, Lyfing, Bishop of Crediton (in office 1027−46), held aloof, but eventually agreed to the translation of the relics. He then sent gifts to the church, including two bells (possibly hand bells), enough lead to roof the entire building and a ‘beautifully worked door’ for the vestry. The martyr’s staff had been found with the relics and this was ‘decorated magnificently with gold and silver and precious gems’.

By this time, Stoke — or Hartland — had become one of about 26 early British religious sites across Devon and Cornwall that had risen to become significant minsters, largely under the growing influence of the West Saxon kings and their clients. Moreover, from the Domesday survey of 1086, we know that the 12 secular canons at Hartland were maintained by 12 ploughlands (an area difficult to calculate, but undoubtedly substantial).

In the event, during the reign of Henry I (r. 1100−35), many old English minsters were given over to communities of the increasingly popular regular canons. These, too, were priests, although they followed a fully communal and celibate religious life, eventually under the guidance of the Rule of St Augustine. Indeed, apart from serving as an important badge of legitimacy, it was the adoption of the Rule that led to the birth of the ‘Augustinian canons’. The label is applied to a very large, but rather loose-knit, congregation of medieval religious houses, of which numerous examples are known from across the British Isles.

In the South-West, it was William Warelwast, Bishop of Exeter (1107–37), who was the prime mover in the introduction of Augustinian canons to the ancient minster sites at Bodmin, Launceston and Plympton. Hartland was to survive a little longer, into the reign of Henry II. Precisely how the initiative for its reform came about is unclear, but there was undoubtedly some form of agreement between the Dynham (or Dinham) family, lords of Hartland, and Richard of Ilchester (d. 1188), then Archdeacon of Poitiers and later Bishop of Winchester.

Unusually, in about 1165−69, Geoffrey Dynham made over both the church and the endowments of St Nectan’s to Ilchester. Geoffrey’s brother, Oliver, gave further lands and the enterprise was clearly endorsed by both Bishop Bartholomew of Exeter (1161−84) and the King. In this way, it was presumably Ilchester who managed to negotiate the introduction of a community of Arrouaisians to Hartland. Named after their French mother house of St Nicholas at Arrouaise (Pas-de-Calais), the Arrouaisians — who already had a small group of English houses — had emerged as a distinct order within the wider congregation of Augustinian canons. In addition to the Rule of St Augustine, they followed a fairly strict customary, more akin to that of the austere Cistercian monastic order.

To begin with, the founding community may well have worshipped in the existing church at Stoke. It was, however, Oliver Dynham who had provided the necessary land alongside Abbey River to allow for the construction of a substantial new church and a full complement of monastic buildings.

Initially, the church doubtless featured a comparatively short presbytery, transepts to the north and south of the crossing and a long nave. A tower may have been planned at the west end from the outset. To the south, around an open cloister garth, were the three principal ranges of monastic buildings. The east range housed the canons’ dormitory, the south their refectory and the west — on the site of the present house — is likely to have been set aside for the abbot and his guests. All these buildings would surely have been completed in their original form by the early 13th century.

Meanwhile, it was a member of the late-12th-century community at Hartland who first composed the St Nectan hagiography (later copied into the Gotha manuscript). Carefully, the author not only places the events in the saint’s life in the immediate topography, but also the miracles associated with his relics. The Arrouaisian canons became guardians of the shrine at Stoke, noting that Nectan’s ‘tomb rises high in the middle of the choir’. On the reverse of the abbey’s great seal was an image of the saint’s severed head.

The endowments given to Hartland’s medieval community ensured that it was a comparatively prosperous house, certainly when compared with many Augustinian foundations across England. However, when the abbey was visited in 1320 by Walter Stapledon, Bishop of Exeter (1308−26), he apparently found the buildings in a less than satisfactory state.

The canons’ dormitory was described as close to ruin, the choir in the abbey church was dark (perhaps too small and architecturally dated), the roof of the tower (belfry) required attention and the lavabo — where the canons washed their hands before entering the refectory — was badly arranged. The Bishop also indicated the need for a parlour. He was probably concerned with discipline: a parlour was the place set aside for essential conversation, without breaking the rule of silence in the cloister.

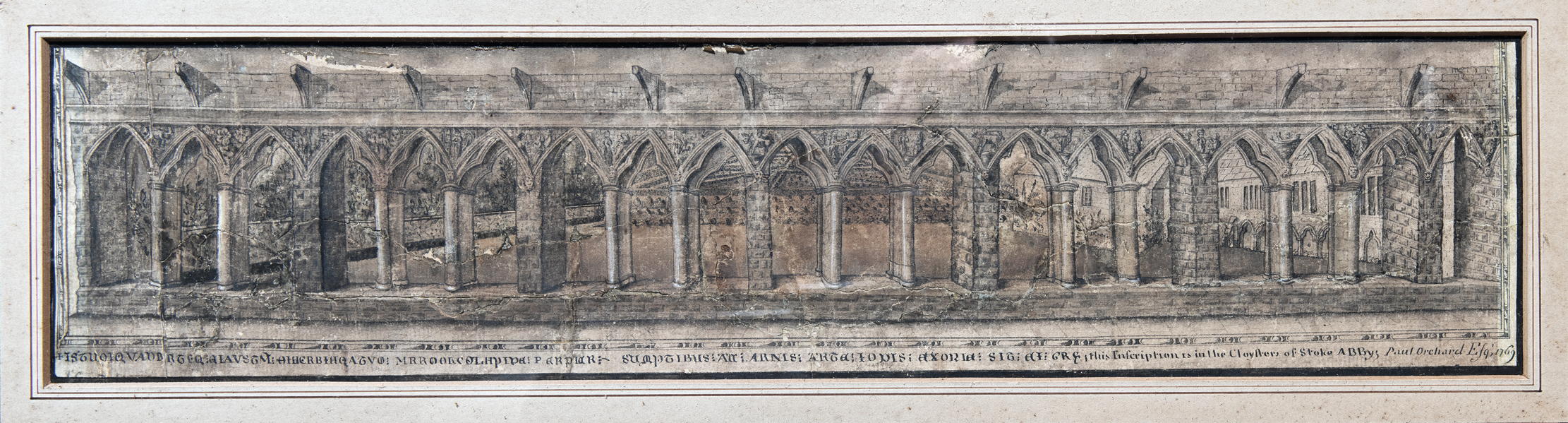

It was presumably in the wake of this visitation that Abbot John of Exeter, who ruled in about 1300−30, began a programme of rebuilding, of which there is a prominent survival on the east side of the present house. Here, at ground level, is the outer line of a cloister arcade, featuring smart trefoil-headed bays. Remarkably, the work bears an inscription, which appears to read: ‘This square cloister was completed and adorned with marble at the expense, during the time, and by the skill of the abbot, John of Exeter. To him thanks.’ The columns are not of the original ‘marble’. They must have been replaced during the construction of the present house by Paul Orchard in the years after 1779, when salvaged fragments of the arcades were also introduced to the west side of the house (Fig 6).

Interestingly, Orchard captured the original form of the arcades in a drawing of 1769 (Fig 5), which appears to reveal antiquarian interests. His view is from within the west walk of the cloister, looking to the east, and must in part be read as an idealised reconstruction (a chimney stack shown in other drawings has been omitted). There is evidence in the surviving fabric for the inner and outer lines of trefoiled arches it shows. These were arranged in groups of three bays, with intermediate supporting columns. As a further indication of quality, the inner spandrels featured figure sculptures, possibly linked to the Exeter Cathedral workshop.

In a watercolour (Fig 2) offering a wider perspective before Orchard’s rebuilding (perhaps of 1767), there is additional evidence for the layout of the abbey. Effectively, the lawn at the centre of the view represents the medieval cloister. To the right (north), the tower that stood at the west end of the church survives. Next to this stands the range that flanked the west side of the cloister. By the later Middle Ages, the upper floor almost certainly accommodated the abbot’s great hall and withdrawing chamber. One of these must be represented by the three windows with traceried heads. In the range along the south side of the cloister, the canons’ refectory is likely to have been at first-floor level. Notably, both the west and the south ranges extended over the cloister walks, explaining the need for the substantial intermediary supports within the arcades. An early 20th-century excavation, the details of which seem to have been lost, yielded further information about the abbey plan and its furnishing (Fig 3).

In 1535, with the drama of the Dissolution just around the corner, the annual income of Hartland was assessed at some £306. Although it survived the Crown’s first assault on the monasteries in 1536, closure was merely a matter of time. In February 1539, the house was surrendered to the King’s commissioners by the last abbot, Thomas Pope (1535–39), with the prior and only three other canons. Seven years later, in January 1546, the house and site of the late monastery of Hartland were granted to William Abbott (d. 1570), described as ‘sergeant of the [King’s] Cellar’, for a fee of £668. We will trace its subsequent history next week.

Visit www.hartlandabbey.com to find out more about the Abbey’s history and planning a visit.

Credit: Paul Roberts/Picfair

50 great things to do in Britain that won't cost you a penny

From moonlight to museums, birdsong to the Old Bailey, Kate Green and Giles Kime find 50 gloriously free things to

Credit: Alamy

Purbeck Heaths becomes the first 'super' National Nature Reserve in the UK

Dorset's Landowners have combined three existing NNRs to form a biodiverse haven for wildlife, with the environment seeing phenomenal benefits

21 joyous pictures of Britain to raise your spirits on the first day of Spring

There's never been a more important time to get out into the countryside and smell the roses. Or watch the