Inside Madresfield Court, the house that inspired Evelyn Waugh’s 'Brideshead Revisited'

John Goodall looks inside Madresfield Court in Worcestershire — home of Lucy and Jonathan Chenevix-Trench — and the family story that inspired Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited. Photographs by Paul Highnam for Country Life.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

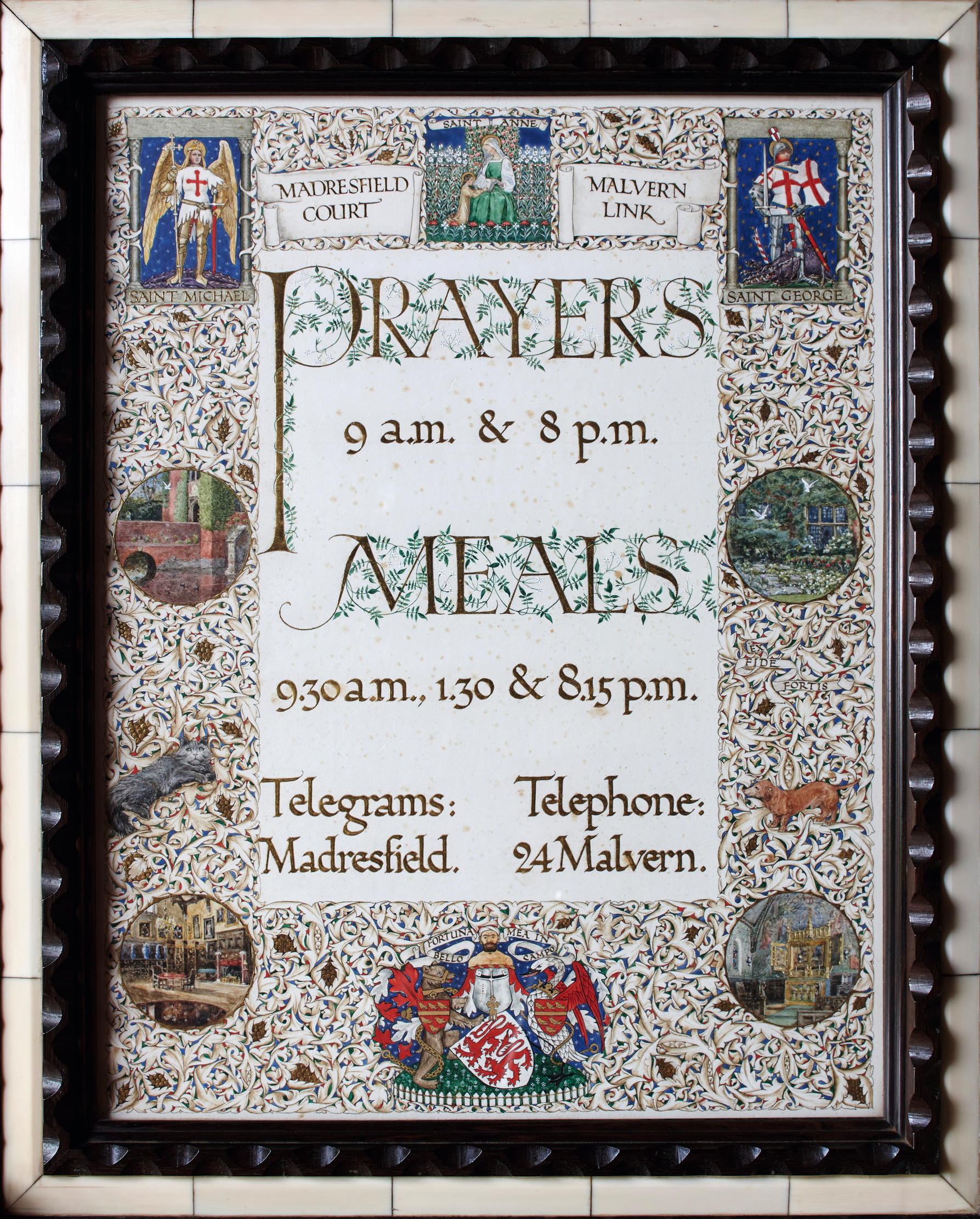

Hanging just inside the front door of Madresfield Court is a framed notice in the form of an exquisitely illuminated manuscript page (Fig 1). It presents erstwhile visitors with a summary of all they needed to know during their stay. The times of prayers and meals take pride of place and, beneath them, are the telegram address and telephone exchange number of the house. Across the top of the intricate foliage border are the figures of saints and the name of the nearest railway station, Malvern Link; at the bottom the arms of Earl Beauchamp. To the sides are four vignettes — a view of the moat, gardens, dining hall and chapel — and portraits of a dog and cat.

The notice is a relic of Madresfield’s busy social round in the years leading up to the First World War, when it was the home of the Liberal politician and discerning patron William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp, who had inherited this ancient family seat in 1891 aged 18. The story of his remarkable life and fall from grace, as well as the links between the house, his children and the novelist Evelyn Waugh, are central to Jane Mulvagh’s acclaimed history Madresfield: The Real Brideshead (2008).

The Earl inherited High Church sensibilities from his father and, from a young age, was interested in the Arts. He even practised them and objects still in the house show him to have been both an accomplished amateur sculptor and an embroider. His public career began very early in life with his election as Mayor of Worcester in 1895, then, even more remark-ably, in 1899, he was unexpectedly — and briefly — made Governor of New South Wales. On May 15, 1902, having returned to Britain, he met Lady Lettice Grosvenor, elder sister of the Duke of Westminster, at a Park Lane dinner party. She shared with him an intense religious feeling and the couple became engaged only two days later.

It was in the context of their marriage that the pair adapted and modernised the south wing of Madresfield. As described last week, this part of the house had been reconstructed in the 1860s, but, from 1902, the library — expanded from a Victorian billiard room — and chapel assumed their present form. Work to the former was planned and overseen by the craftsman and idealist C. R. Ashbee, employing the carvers Alec Miller and Will Hart from his Guild of Handicraft, which had recently transferred from urban Whitechapel to rural Chipping Campden, Gloucestershire.

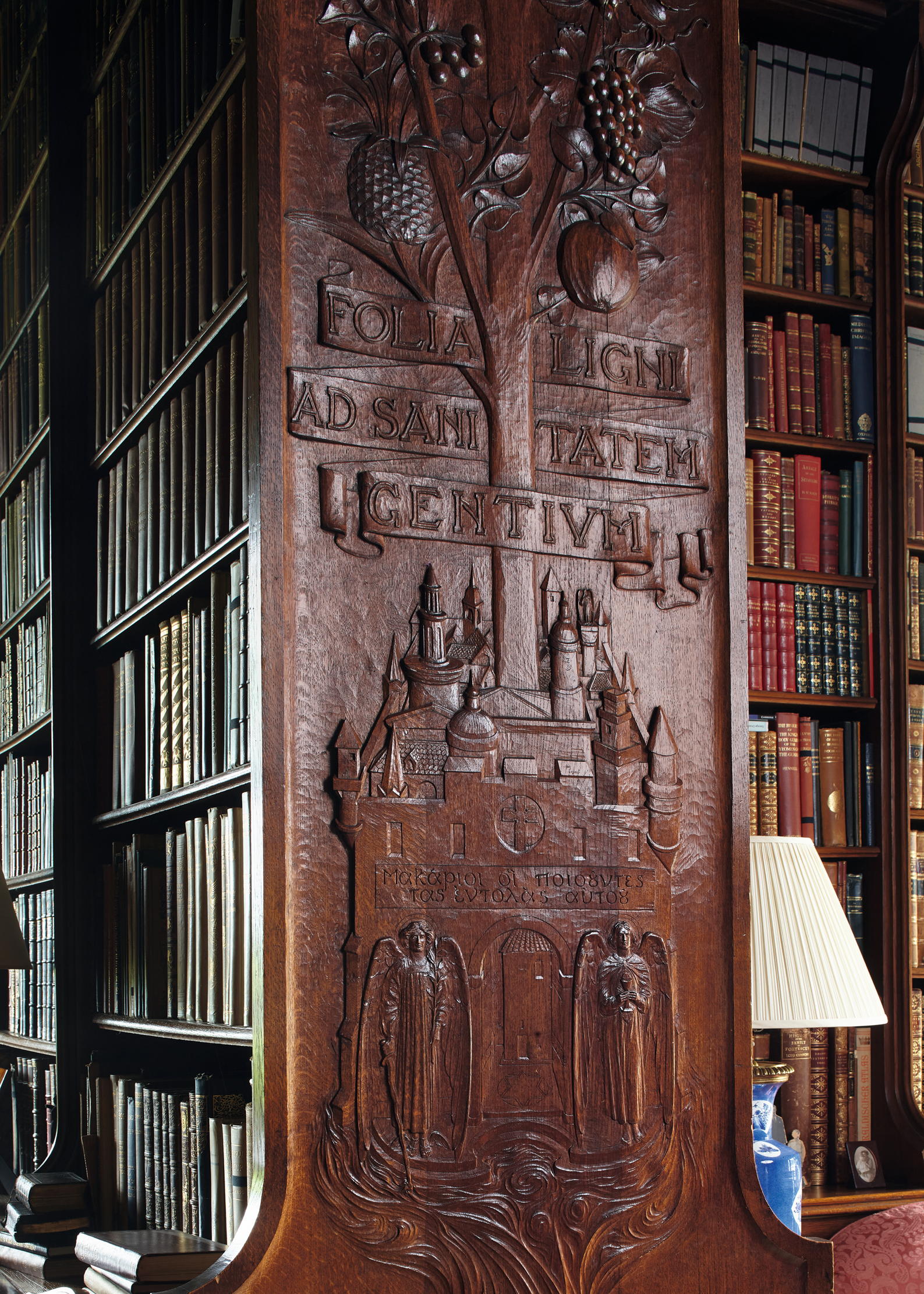

In the library, the bindings of the books and the furnishings compete for the visitor’s attention and wonder. Presiding are the ends of two projecting bookshelves that rise to the ceiling (Fig 4). One is carved in low relief with the Tree of Knowledge, its branches and roots populated with animals and birds. Beneath it, Eve offers Adam the apple under the watching gaze of the Serpent. A Latin inscription exhorts: ‘The beginning of wisdom is fear of the Lord.’ The other shelf end presents the Tree of Life, which rises from the walls of the Heavenly Jerusalem, its branches laden with fruit (Fig 3). A quotation from the Book of Revelation reads ‘the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations’; the Latin folia ligni punningly refers to leaves and pages.

The doors of the room possess striking metal doorplates decorated with the Beauchamp arms and are ornamented with low-relief carving. Their imagery and inscriptions celebrate the pursuit of knowledge and beauty. One at the far end shows a scholar at his desk. Two inscriptions refer to the books that surround him: ‘They are all silent’ and ‘You are doctors to me’. Behind him is a crucifix.

Open this door and you pass from one marvel of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement into the lobby of another: the chapel. Again, this combines images and text in a manner reminiscent of the sumptuous interiors created at Cardiff Castle and Castell Coch in South Wales a generation earlier by the Marquess of Bute (COUNTRY LIFE, August 18, 2021).

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

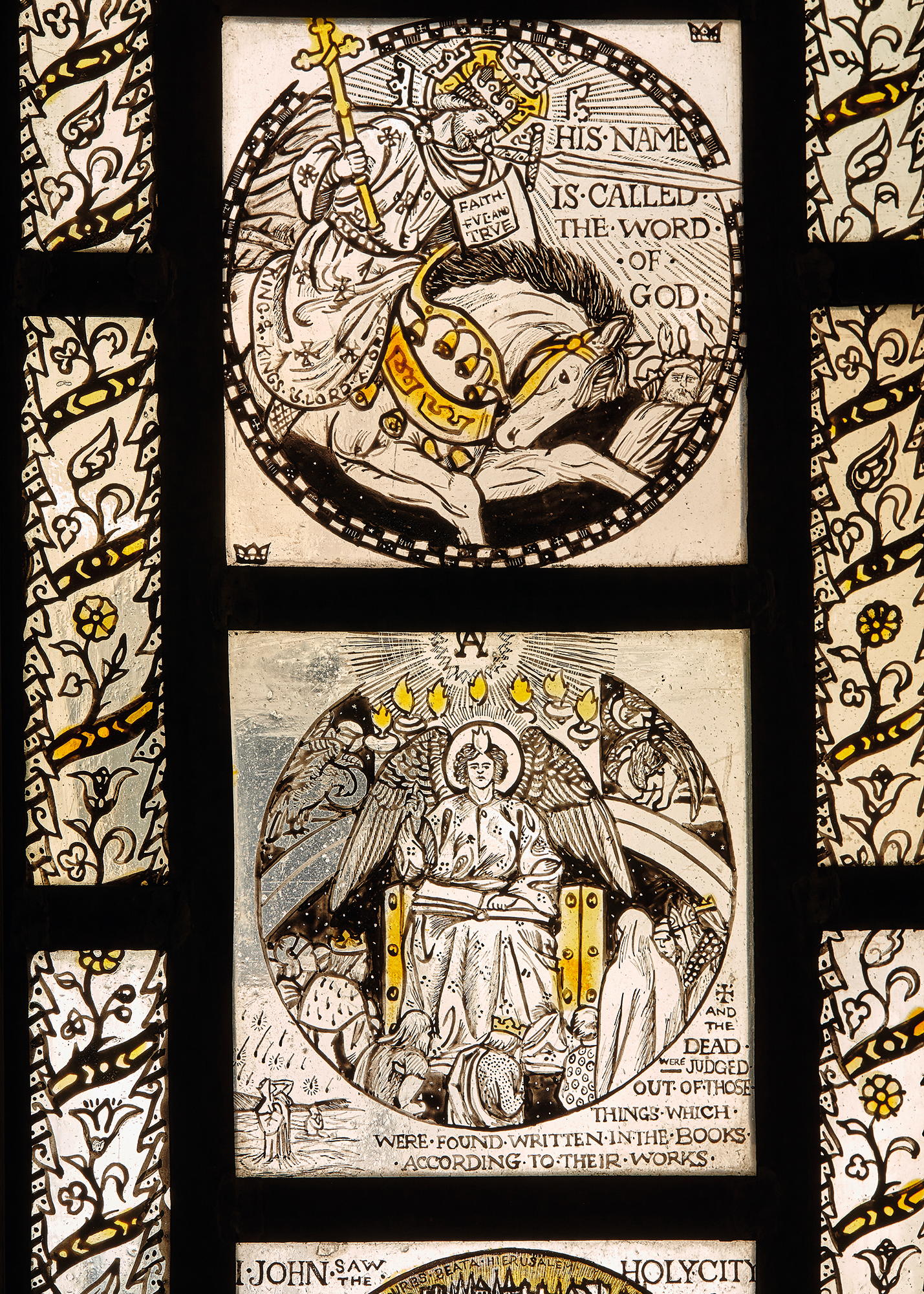

The decoration of the chapel is the outstanding work of Harry Payne (with three assistants), who studied and later taught at the Art School in Birmingham and was interested in watercolour and stained glass. The work was Lady Lettice’s wedding gift for her new husband and took more than two decades to realise, with the Earl closely involved throughout. Its iconography relates to that of the library, with an emphasis on the Book of Revelation. Walking into this intimate space, the visitor is catapulted into another universe, an enclosed garden populated with birds and filled with flowers, timeless, seasonless and serene; what Jane Mulvagh has called a ‘Garden of Albion’.

A short, anonymous pamphlet of about 1907 offers an illustrated meditation on the painted decoration of the interior. Its prefatory quotation from the Song of Solomon, ‘A garden enclosed is my sister — my wife’, introduces the complex intertwined themes of marriage, heaven and praise that are celebrated here. The text goes on to explain how a garden with its smells and colour speak of the glory of God. Here, the walls ‘have caught the glory of that world outside: overhead is green, the colour of charity and peace; honeysuckle clings to the rafters, doves circle around them… Roses climb about the trellis that encloses our garden’.

The pamphlet continues with a description of the two figures who command the side walls of the interior. To the right is St Michael, archangel and arbiter of the Last Judgement. Beside him is the Recording Angel, prepared to note good and evil deeds, ‘a challenge in his eye’. In his book is the inscription ‘This is none other than the House of God, and this is the Gate of Heaven’. Opposite is the Virgin, the crushed violets beneath her feet ‘sweeter for her tread’. Over the altar is Christ in glory enthroned on the Tree of Life above a rainbow, ‘the water of life, as clear as crystal’, pouring from beneath his feet (Fig 10). Angels offer praise and, on the side walls, rush towards him.

Within the gilded altar that forms the focus of the interior is Christ ‘with the Invitation on his lips’: ‘Come unto me all ye who labour.’ Behind him ‘is spread the table of the Marriage-feast’ and angels bearing the ‘garments of praise’ that must be worn by any who would attend. In the wings are a harvester and vine dresser with the Israelites gathering Manna in the wilderness, the bread of Heaven that shall be ‘given to him that overcometh’.

What this pamphlet description omits to describe properly — and what gives such impact to this scheme — are the almost life-size family portraits that flesh out this astonishing display. They connect this celestial vision to the living world and the family that prayed here. Flanking the altar are the kneeling figures of William and Lady Lettice, the latter in her wedding dress, and on the walls their children. Only the figures of the two eldest — William (b.1903) and Hugh (b.1904) — are mentioned in the text, but they are not identified, merely described as ‘Living jewels dropped unstained from Heaven’. The angel playing a psaltery who presides over them is a portrait of their nurse (Fig 7).

All seven children appear, the last of them born in 1916, and contriving space for them must have been a challenge. Some read manuscripts (Fig 8) and others play. Also preserved in the chapel are their personalised prayer books, each one with a written dedication from their father. Their names also appear on the chapel lobby screen (Fig 6), which is otherwise filled with square glass panels, each one bearing an image that illustrates an accompanying text from the Book of Revelation (Fig 9). Most poignant of all, how-ever, is the stained glass in the lobby window, also executed by Payne. It depicts Christ healing the centurion’s servant (Luke 7:1-10), with a portrait of the Earl as the centurion.

Work to the chapel was under way when attention turned to the staircase hall, its huge volume created during the late-19th-century alterations. In classic late-Victorian form, it creates a circulation space with a gallery on the first floor giving access to the bedrooms. From at least 1908, designs for this interior were under discussion with Randall Wells and Ernest Gimson and the imposing fireplace was a wedding gift from the Duke of West-minster. Its staircase with heraldic beasts on the newel posts and crystal balusters is at once Gothic Revival and Art Deco (Fig 2).

The Earl was by now well experienced in public life. Office in the Royal Household graduated into a place in the cabinet of Prime Minister Asquith, where he was a vehement advocate of peace as the First World War loomed. There were other prestigious offices besides, including his appointment as Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1913 and the Chancellorship of the University of London from 1929. He entertained at Madresfield throughout in considerable style. Describing a house party in 1901, Viscount Mersey noted that: ‘Everything was done in great style: minstrels in the gallery at dinner, numbers of footmen in powder and breeches and a groom of the chambers worthy of Disraeli’s novels.’

The prominence of the footmen was not fortuitous. Over the same period, the Earl acquired a reputation as a homosexual and disapproval mounted. It might have mattered for little, but for the fact that his brother-in-law, the Duke of Westminster, began to pursue him with all the determination of extreme hatred. He forced the estrangement of Lady Lettice from her husband and took her, tog-ether with her youngest child, into his care. In 1931, the Earl was driven into European exile and was refused permission to return for his wife’s funeral in 1936. The authorities relented, however, when his second son died a few months later. The Earl himself followed to a Madresfield grave in 1938.

During the scandal, the Lygon children sided with their father, but the image of familial order and affection presented in the chapel was overturned. Indeed, it was disfigured, because Lady Lettice’s image was whitewashed over. Her marble bust was found years later in the moat. It has been restored to the house, but at a distance from that of her husband.

Madresfield escaped requisition by the army during the Second World War and was instead designated as a possible evacuation home for the Royal Family. To an unusual degree, therefore, its principal interiors preserve their early-20th-century character. When the 8th — and last — Earl Beauchamp died in 1979, the house passed to Lady Rosalind Morrison, who lovingly maintained it. Despite that care, the house was in need of renewal when the present owner — Lucy Chenevix-Trench, great-niece of the 8th Earl — arrived with her husband, Jonathan, and four young children in 2012.

Their first task was to re-roof the building and modernise its services, work overseen by Sarah Butler of Donald Insall Associates. It is now heated with a biomass boiler. The whole interior has been subtly renewed and brought back to order under the direction of the interior-design company Todhunter Earle. Where necessary, decoration has been refreshed, pictures restored, chairs reupholstered and appropriate furniture brought. New bedrooms have been created and bathrooms installed. This has been done with such sympathy that a first-time visitor would struggle to know that anything had changed.

To make Madresfield Court more practical as a modern home, the building has also been turned back to front. Today, the 1870 servants’ bridge is the approach to the family front door. Opening off the new hall is a kitchen/living room designed with specialist advice from Jane Taylor (Fig 11).

This is a modern interior in keeping with the character of the house, but there is an attractive detail that would particularly appeal to the 7th Earl: the handles of the cupboards are cast from sculptures of leaves and feathers carved by the owner. They make tangible the contribution of the 28th — and 29th — generation of the family to live in this outstanding house. Without the benefit of a Jennens legacy, they aim to sustain the house with new businesses that would appeal to both the 6th and 7th Earls: gardening-clothing company Mad About Land, inspired by the chapel murals, and a restaurant in Malvern that showcases the regeneratively farmed produce from the estate.

Visit www.madresfieldestate.co.uk

900 years old, one careful owner: How Madresfield Court has come down the centuries in the hands of one family

John Goodall looks at the early evolution of Madresfield Court, Worcestershire — the home of Lucy and Jonathan Chenevix-Trench — to

Madresfield Court: A Worcestershire garden where new and old combine in perfect harmony

Steven Desmond visits Madresfield Court in Worcestershire, where high Victorian romanticism has been blended with modern ideas to create a

A walk in the footsteps of Evelyn Waugh at Madresfield Court, the real-life inspiration for Brideshead Revisited

Fiona Reynolds takes a walk around the home that captured Evelyn Waugh’s imagination, finding a place that is both intriguing

John spent his childhood in Kenya, Germany, India and Yorkshire before joining Country Life in 2007, via the University of Durham. Known for his irrepressible love of castles and the Frozen soundtrack, and a laugh that lights up the lives of those around him, John also moonlights as a walking encyclopedia and is the author of several books.