Port Sunlight, Merseyside: A shining example of how planned housing can be humane, successful and beautiful

A fortune made from soap manufacture created one of the largest and most impressive garden towns in Britain. Steven Brindle reports on this Edwardian dream-world of English vernacular architecture.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

William Hesketh Lever (1851–1925), later the 1st Viscount Leverhulme, was the son of a wholesale grocer. He was born in Bolton and educated at the town’s church school. At the age of 16, he entered his father’s business and studied the habits of its customers: the working-class housewives of Lancashire.

Lever realised that if he concentrated on a staple product and marketed it with sufficient skill on a sufficient scale, the family business could be transformed into something huge. The product that he chose was soap, hitherto usually made of animal tallow in long bars that were sliced up at need.

In 1884, he founded Lever Brothers with his younger sibling James Darcy Lever (who became an invalid and died in 1910). Their product was of better quality, being made of vegetable oil, and was produced in individual cakes neatly packaged with its brand name: Sunlight Soap. In 1885, they leased a factory in Warrington and the business expanded amazingly.

Lever looked for another site and, in 1888, he bought a large tract of rather depressing, marshy land on the Wirral. There, he began to build a vast factory, together with a planned village for his workers, and named it Port Sunlight. The factory started production in 1889, by which time the first rows of cottages were rising. Lever was just 38 years old at the time.

The new factory, with Lever’s energetic management and flair for marketing, brought Sunlight Soap to the whole nation. It was a classic Victorian success story – by 1897, his personal fortune was more than £1.25 million and, by 1906, the business was global and he was worth more than £3 million. Lever was a Liberal, a fervent admirer of Gladstone and a firm believer in individual responsibility and self-help.

However, there was much more to him than that. Lever had a highly original, creative mind and a very forceful personality; Sir Angus Watson, a contemporary and sometime employee, described him thus: ‘Short and thickset in stature, with a sturdy body on short legs and a massive head covered with thick upstanding hair, he radiated force and energy.’

Lever was passionately interested in architecture and his closest friend was a Bolton architect, Jonathan Simpson. At one time or another, he owned 12 houses and a full catalogue of his architectural projects would be a substantial book. Port Sunlight is arguably his greatest creation and expressive of his remarkable personality – it was at once idealistic and practical, as well as dictatorial and extraordinarily generous.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The village represents two strands in English planning and architecture. Lever wanted to combine the spacious layouts of the Picturesque tradition, as seen in late- Georgian and Victorian suburbs such as Bedford Park, with the scale of industrial housing at New Lanark in Scotland and Saltaire in West Yorkshire.

He loathed the cramped, squalid terraces that had sprung up all over the industrial North-West, and wanted to do better by his employees. His benevolent intentions were absolutely genuine, but they were underpinned by views that would be unimaginable today.

As Lever wrote, he could have offered his employees a bonus, but believed that ‘£8 is… soon spent, and it will not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the form of bottles of whiskey, bags of sweets, or fat geese for Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave this money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything which makes life pleasant—viz., nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation. Besides, I am disposed to allow profit sharing under no other form but that form’.

The property that was initially purchased in 1888 included 24 acres for the factory and 32 acres for the village. The first factory building rose next to a wharf on Bromborough Pool, an inlet of the Mersey. At the time, the pool opened into muddy tidal creeks forming an E-shape. In the initial stages of building the village, about 1888–97, the southernmost of these creeks was drained as The Dell, which remains a picturesque green space. Roads were laid out around this landscaped centre, with groups of cottages in blocks facing towards them, so the cottages would present their best face to the roads and the backyards, outhouses, lines of washing and allotments were neatly hidden away.

The first houses were designed by William Owen, the Warrington architect to whom Lever entrusted the factory. Soon, other north-western firms were engaged, including Douglas & Fordham of Chester, Grayson & Ould of Liverpool and J. J. Talbot of Liverpool. Between them, they were responsible for most of the first phase of the village (about 1889–97). No two groups of cottages are alike and in the first phase are pretty, but with much use of red pressed brick and black-and-white ‘half-timber’.

From the outset, there were public buildings and shared buildings, such as Gladstone Hall (opened by the statesman himself in 1891), built as a men’s dining hall, and the Schools (1894–96), now the Lyceum, and Hulme Hall (1900–01), built as the women’s dining hall and later used as an art gallery.

Lever was involved in every stage and approved every design. Indeed, between 1896–97, he and his family lived in the village, at Bridge Cottage just off the Dell (1892). The business continued to expand: in 1895–96, the ‘Number 2 Soapery’ was added to the original factory, effectively doubling it in size. More land was purchased to the north and, by 1900, Port Sunlight grew to 400 houses. In 1893, Lever visited the World Columbian Exposi-tion in Chicago and was impressed by its formal, Beaux-Arts layout – after about 1900, the planning of Port Sunlight gradually evolved in this direction.

In 1910, having filled in the creek channels, there was a competition for pupils in the Liverpool School of Architecture for a master plan for the remaining stages of the village. It was won by a third-year student, Edward Prestwich, who suggested developing a north-south axis, the Diamond, into a central axis crossed by The Causeway.

At the intersection today is the war memorial, planned from 1916 by Sir William Goscombe John. As a result, the informal, picturesque planning of the earlier part of the village around The Dell, to the south, gives way to straighter lines around these broad, formal features to the north.

As more houses were planned, Lever introduced many more architects to design them. There were other northern firms, such as Lever’s friend Simpson and his son James Lomax-Simpson, Lockwood & Sons of Chester and Sir Charles Reilly of Liverpool. There were also prominent London architects, including Sir Ernest George, Maurice Adams and Sir Edwin Lutyens. The variety of design continued and the houses from the Edwardian phase have a softer, more mellow palate of materials, more redolent of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement. By the time the First World War broke out in 1914, the outlines of the village were largely complete, although houses continued to be added up to the time of Lever’s death in 1925, and beyond.

The magical quality of Port Sunlight arises in part from generous planning—the overall density is about 10 houses per acre – and the aspect of the houses over unbroken lawns towards the roads. Then there is the variety of designs and materials, as well as distinctive detailing. Underlying this visual variety, however, the houses are of only two main types. The smaller ‘kitchen cottages’ were planned with a kitchen, scullery and bathroom on the ground floor and three bedrooms above, as the larger ‘parlour cottages’ have a parlour added to the ground floor and an extra bedroom above. The provision of bathrooms to most houses, and the provision of a gas-supply to all of them, reflected Lever’s determination to provide a better standard of living – the estate was converted to electricity in the 1920s.

Then there is the wealth of facilities including shops, an open-air swimming pool, a large inn, a school and a hospital. Two other public buildings, however, stand out: the church and the art gallery. They were Lever’s personal gifts, paid for out of his own pocket (the rest of the village was paid for by the company). Christ Church (1902–04), designed by Owen and his son, Segar, is a splendid work of late-Perpendicular revival in dark-red Cheshire sandstone. Lever was himself a Congregationalist, but, remarkably, the church was planned to be non-denominational, with services from a range of visiting clergy.

The same firm designed the superb, but very different, Lady Lever Art Gallery. This closes the northern end of the Diamond and it is a masterpiece of Beaux-Art Classical architecture, in marked stylistic contrast to the rest of the village, but integrated into it with great skill. The gallery commemorates Lever’s wife Elizabeth Ellen Hulme, the daughter of a Bolton mill-manager, whom he married in 1874; her placid, domestic personality was the perfect foil to his dynamism and it was a very happy marriage.

Lever was made a baronet in 1911, but his wife died in 1913, before he was raised to the peerage. In her memory, he added her name to his to create his title, becoming Baron Leverhulme in 1917 and Viscount Leverhulme in 1922. As a result, Hulme was Lady Lever, but not Lady Leverhulme, hence the gallery’s name. Lever collected art on a grand scale and from these vast holdings he chose a range of paintings, sculpture, furniture and fine-art objects to give to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, which opened in 1922.

Lever died in 1925 and there are two monuments to his memory in the village. West of the art gallery rises a tall, black obelisk (1930) designed by Lomax-Simpson with further allegorical sculptures by Sir William Reid Dick. At the west end of Christ Church is a more personal table monument with effigies of Lever and his wife carved by Goscombe John, commissioned by Lever after her death.

Port Sunlight has evolved, but its visual qualities have been well protected. Lever’s company, which became Unilever in 1929, repaired the village after wartime bomb damage and carried out a sensitive modernisation of most of the houses in the 1960s. In the 1980s, the company began to sell off the houses and the restriction that only employees could live there was lifted. This might have spelt trouble, but the village’s future was safeguarded by the formation of the Port Sunlight Village Trust in 1999. Unilever transferred its property to the trust, which thus owns about 300 of the 900 or so Grade II-listed buildings. These are let, generating an income stream that enables the trust to maintain the public buildings and open spaces to a high quality. It sets standards for the management of all the houses through restrictive covenants, as well as the listing and Conservation Area controls. The trust encourages visitors and has opened a fine museum in the former Girls’ Club close to the art gallery, together with a furnished ‘kitchen cottage’, which is open to the public. A walk around the village with a visit to the museum and the art gallery makes an excellent day out. Unilever, which happily maintains one of its largest factories on the original site, remains benevolently involved in the background. Its founder would surely be pleased.

Through the storms and upheavals of the 20th century, Lord Leverhulme’s village has thrived, and it remains a shining example of how planned housing can be humane, successful and beautiful.

Credit: Russell Hart / Alamy Stock Photo

The best places to live near Manchester – and what you could get for your money

If you're happy to commute from within an hour of Manchester, there's a world of possible places to live. Eleanor

The Tudor mansion in Sussex where Lutyens and Jekyll pooled their talents

Legh Manor: The Tudor mansion in Sussex where Lutyens and Jekyll worked together

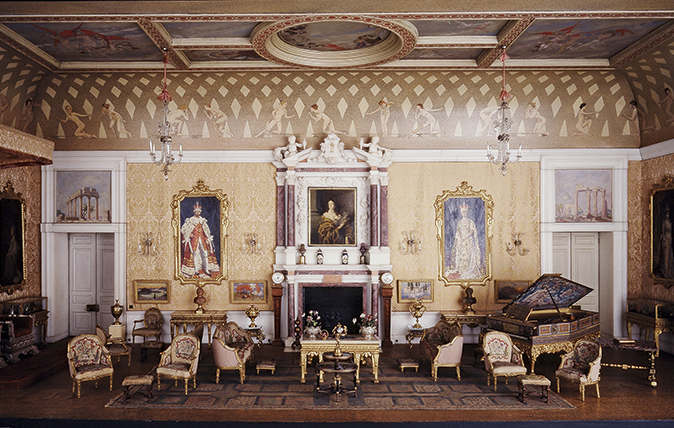

A doll's house fit for a queen: How Lutyens created a Lilliput for Queen Mary

A miniature palace designed by Lutyens and promoted by Country Life offers a fascinating perspective on the 1920s, as Gavin

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.