The Summerhouse at Grimsthorpe Castle, built by Sir John Vanbrugh, restored as a true labour of love

The restoration of a Lincolnshire estate building by Vanbrugh has created a delightful cottage, where ingeniously conceived modern decoration records the lives and interests of the couple who undertook the work. Roger White tells the tale of The Summerhouse, Swinstead; photographs by Robin Foster.

Although Grimsthorpe Castle in Lincolnshire is one of England’s greatest country houses, and its thunderous entrance front is Sir John Vanbrugh’s final masterpiece, it is still less well known than it deserves.

Even less familiar is the Summerhouse, which is also almost certainly from the hand of the master. Distantly visible across the park from the Castle, but invisible from any public road, it is nearest to the little village of Swinstead, from which it lies concealed behind a screen of trees. Any building by one of this country’s greatest and most original architects is worthy of note, but the Summerhouse is notable, too, by virtue of its recent restoration.

Vanbrugh’s connection with the Bertie family of Grimsthorpe went back many years. He is recorded as travelling to The Hague in 1688 with Robert Bertie, then Lord Willoughby d’Eresby (created 1st Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven in 1715), and the younger brother Peregrine was, in 1694, described as Vanbrugh’s intimate friend. This was before his sudden conversion to the practice of architecture, which seems to have happened in the late 1690s. When it did, however, it was no surprise that Bertie commissions came his way.

The actual rebuilding of Grimsthorpe is usually thought to have begun with the north front in 1722 and was certainly completed after the 1st Duke’s death the following year. However, a plan of the previously existing house is dated 1715 in Vanbrugh’s hand and a preliminary design for recasting the north front may date from this time; indeed, it may be that the centre block was begun some years before 1722 (Country Life, April 17, 2008).

In addition, the Ancaster archives contain two sets of Vanbrugh designs, one for a large house and one for a small, which scholars John Harris and Kerry Downes agree in dating to about 1710. It does seem probable that a smallish Vanbrugh house was actually constructed at Swinstead, but nothing of this building, known as Swinstead Old Hall, survives, although bits of stonework are said to have been reused around the village.

This brings us to the Summerhouse, which Mr Harris suggests provided a visual link between the castle and Swinstead Old Hall, visible, like a piece of stage scenery, on the skyline from the former to the east and from the latter down the slope to the west.

The earliest reference to the Summerhouse is a mention in the Ancaster archives that, in 1735, Thomas Winpenny supplied green leather benches and yellow and red wool hangings for the ‘Old Summerhouse’. The date of construction cannot be established, although its design may have been connected with a visit Vanbrugh paid to his old friend Bertie in 1715.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Stylistically, it can be compared to others of Vanbrugh’s small buildings: the belvedere tower at Claremont in Surrey of 1715 and the water tower in Kensington Gardens of 1716. The belvedere, in particular (which originally loomed above Vanbrugh’s own country house), has taller towers framing a two-storey centre and a roof-top viewing platform between, which was the original arrangement at Swinstead.

The water tower, as did Vanbrugh’s own little house at Greenwich, affected a military air with its false machicolations and this may have been the case with the Summerhouse, too, the tower tops of which were possibly altered in the early 19th century.

In 1821, the architect John Buonarotti Papworth produced designs (now in the RIBA Drawings Collection) for turning the Summerhouse either into accommodation for an estate worker or into a chapel. The former would have provided single-storey wings to north and south and a pedimented room infilled between the twin towers on the second floor; it is not clear whether the whole building would then have been given over to the estate worker and his family or whether the tower rooms would have remained in Bertie usage. In any event, the stripped Classical additions of the early 19th century marry surprisingly well with the bluntness of Vanbrugh’s forms.

The majority of the Papworth drawings relate to the proposed addition of a chapel on the west side of the building, for which the centre of the Vanbrugh structure would have provided a vestibule. Because the chapel (the altar of which would, perforce, have been at the west end rather than the usual east) is designed in a Regency Gothic idiom, the pairing would have resulted in something of a stylistic shotgun marriage.

The justification for the chapel is unclear, as the castle already had its own fine chapel, Swinstead had its medieval parish church, and, traditionally, Bertie family members were buried in Edenham Church on the opposite side of the estate.

The 5th and last Duke died in 1809 and was, indeed, buried in Swinstead Church. He was succeeded by his kinsman Lt-Gen Albemarle Bertie, who inherited as 9th Earl of Lindsey, but he died in 1818 and was followed by his eldest son, George, aged four. The identity of Papworth’s client in 1821 is unclear, therefore, as the 10th Earl was then still only seven; it may have been his mother, the 9th Earl’s second wife, Charlotte. The 10th Earl was of ‘weak intellect’ and something of a family problem, although he lived till 1877.

The chapel remained unbuilt, but alterations were certainly carried out to the Summerhouse and, very likely, by Papworth or his office. The rooftop viewing platform was replaced by a central room lit by austere triple slots and the ground-floor arch was replaced by an equally austere window of five slots to make an enclosed room; probably, at this point, a small extension was applied to the rear elevation, providing the limited accommodation thought adequate for an estate employee. The ground-floor tower windows were blocked, so the Summerhouse lost the transparency Vanbrugh had intended. It may also have been at this point that the tower tops were re-formed with low pyramid roofs, losing the false machicolations that perhaps originally crowned them.

After the First World War, the second-floor room was lined on all four sides with reinforced concrete to form a water tank. During the Second World War, the building saw duty as an anti-aircraft battery and, thereafter, stood empty and unregarded. That is, until one evening in January 1990, when Martin Williams encountered me at a Chelsea dinner party. He was looking for a folly in the Home Counties to rescue, but his ears pricked up when I mentioned the derelict tower on the Grimsthorpe estate.

Curious and enthused, he went home to wake his wife, Gil, who was in bed with flu, and within weeks they drove up to Lincolnshire for an inspection. Although the building was looking austere and unloved — especially in the bleak winter weather — and what became a garden was then a field, it appears to have been love at first sight.

Negotiations for a long lease were lengthened by the sudden departure of the incumbent agent, but terms were at last agreed and plans drawn up. The necessity of increasing the accommodation at the rear of the tower, even modestly, was at first opposed by English Heritage on account of its Grade I status, but a fortuitous encounter with an appropriate senior official on holiday in Italy had the result of unblocking the logjam.

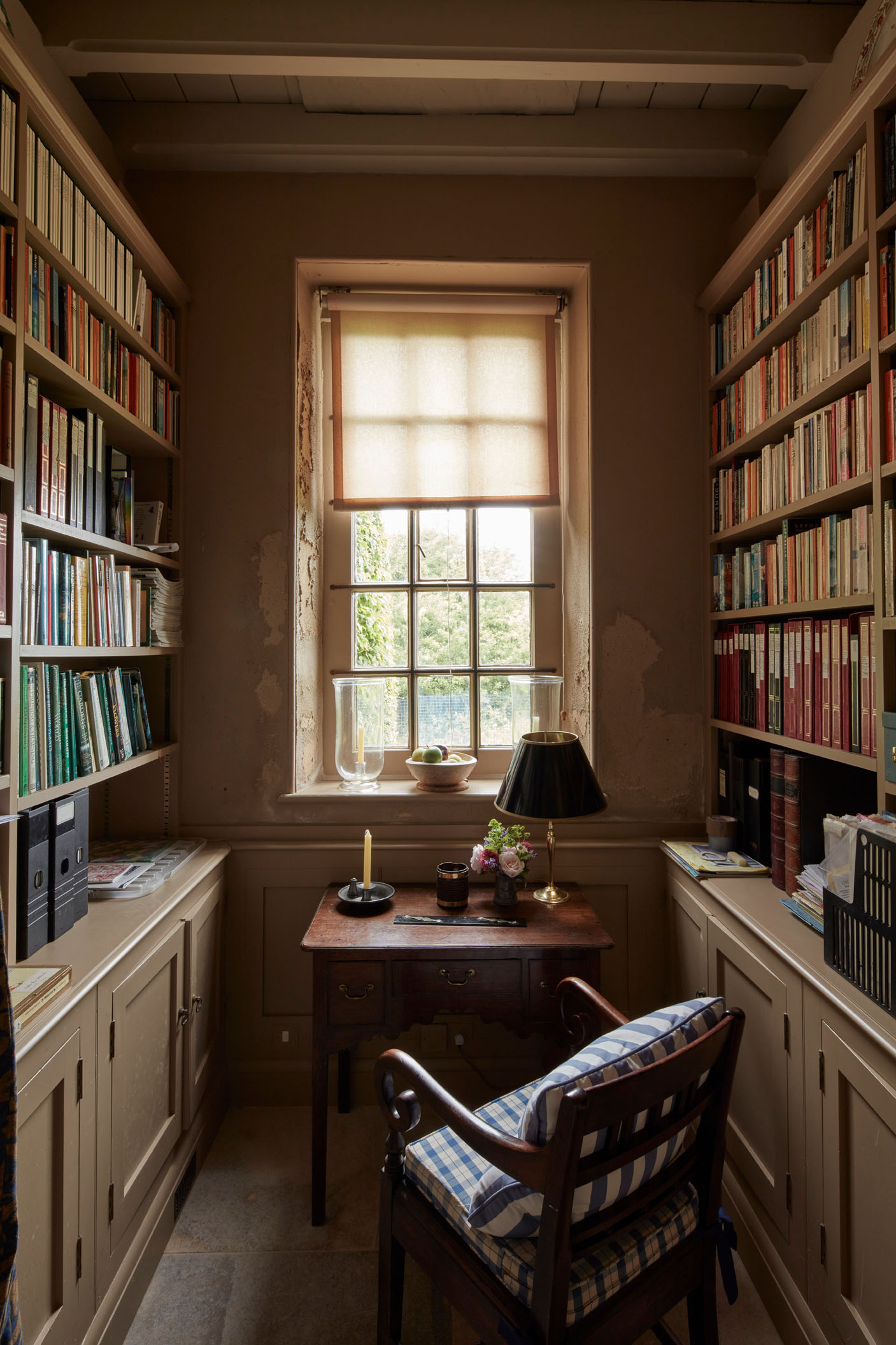

The architect for the project was Michael Barker, who produced a very liveable small house featuring many ingenious touches. The contractor, John Gregory of Corby Glen, was from the local area and the stone for the new rear extension was sourced from Ketton in Rutland. However, the decoration that has made something truly memorable of the previously featureless interior was entirely the inspiration of Gil and, following her tragically unexpected death in 2019, it forms a touching memorial both to her and to the couple’s marriage.

As Gil Darby, Mr Williams’s wife had been a well-known teacher of art history and authority on ceramics, first at the V&A Museum and subsequently at Christie’s Education. To document the couple’s respective lives and interests, the first-floor saloon was frescoed in gouache by William Grantham and Fiona O’Neill in 1992. Gil herself designed the ceiling as a Renaissance take on Pompeii, incorporating four panels with specific personal references: the Dugald Stewart Monument on Calton Hill in Edinburgh, alluding to the city of her education; the V&A, her place of work; the Royal Albert Hall, of which Mr Williams was a trustee; and the William Chambers temple at Osterley Park, where, in the first years of their married life, the couple had a top-floor flat.

Further personal attributes are symbolised by a trug and fork (for Gil’s gardening enthusiasm); a violin to record Mr Williams’s love of music; their astrological signs; a pair of walkman headphones; their respective spectacles; pen and ink for Gil’s writing and lecturing; and a glass of wine for them both.

The new saloon chimneypiece is based on one by Vanbrugh in the Prince of Wales’s Apartment at Hampton Court Palace and the delicate wall panels are the invention of Mr Grantham. They elegantly incorporate what might be termed trompe l’oeil information labels, those flanking the chimney-piece having, respectively, the Williams’s initials and the date of the murals, as well as the day they moved in. A recently painted label on the window wall has Gil’s initials and the year of her death.

The southern tower contains the tightly ascending staircase, the other opens from the saloon as a little ‘cabinet’, as prettily frescoed as the main room. Here the oval vignettes have apt architectural references. Three depict Vanbrugh buildings — the north front of Grimsthorpe, vanished Eastbury in Dorset, and the architect’s own house at Greenwich. The fourth is Scamozzi’s Villa Rocca Pisana, destination of a number of very happy family summer holidays in the Veneto.

Mr Williams says of the Summerhouse interior that ‘Everything speaks of Gil’. This also applies to the gardens, which were created entirely from scratch and are now fully mature. At the rear is a simple lozenge-shaped enclosure that consciously echoes the Duchess’s Bastion in Stephen Switzer’s fortified garden at the castle; behind a single-storey outbuilding is a small formal flower garden with box compartments.

A larger green garden contains a formal canal aligned on the south tower, the severity relieved by terracotta pots of agapanthus, pollarded trees and classical urns on pedestals. High yew and hornbeam hedges provide the necessary shelter in what is quite an exposed location. All this — the gardens, the restoration of the derelict building, the decoration and furnishing of the interior — amounts to a small, but exquisite tour de force of autobiographical record.

Belvoir Castle: From Norman conquest to Regency prodigy

New discoveries in the archives at Belvoir are fleshing out the history of this outstanding castle. John Goodall delves into

Blair Castle: Feudal power, sophisticated patronage, rebellion and romance

Reinvented several times, this ducal seat reveals to Mary Miers the story behind the Rococo palace in the wilds. Photographs

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.