The tale of Knebworth: How does your garden village grow?

A garden city planned by Sir Edwin Lutyens was never brought to completion. Plans to redevelop it today, however, threaten to destroy the character of what was created. Clive Aslet reports.

Although most people will have heard of Knebworth House, in Hertfordshire, the garden village that was developed on the estate in the Edwardian period, with Sir Edwin Lutyens as its consulting architect, is less familiar. This is surprising, given the attention that has been given to garden cities and garden suburbs in general, not least because, around the year 2000, the creation of new garden villages was promoted as a solution to the planning dilemma of where to build more homes in the crowded South of England.

The Department for Communities and Local Government has more recently re-asserted the point in its publication Locally-Led Garden Villages, Towns and Cities (March 2016). Furthermore, bucolic Knebworth Garden Village was important in Lutyens’s career, as a stepping stone — unlikely as it might seem — on the path to the vastly bigger town-planning venture. Astonishingly, before his involvement in New Delhi in India, Central Square at Hampstead Garden Suburb in north London was the only other significant piece of urbanism that he had designed.

Lutyens’s influence on Knebworth, beyond buildings produced under his eye, can still be seen by those who know where to look. This is no thanks to the local planning authority, which seems determined to betray his legacy, despite strenuous local efforts to perpetuate it. Rather than take account of local circumstances, planners point at national policy, which they seem insistent on applying.

The connection to Knebworth came through Lutyens’s wife, Lady Emily Lytton: the house was her family’s seat. In truth, she did not spend many years there when growing up. Although her father, a diplomat, poet and Viceroy of India, was made an Earl, he had little income to support the title; besides, he was made the British ambassador to France in 1887 and it was in Paris that he died in 1891. Knebworth House remained let even after the Earl’s eldest son, Victor, came of age in 1897. After his marriage five years later in 1902 to the beautiful, lively Pamela Chichele Plowden, the tenant allowed the newly-weds to have their honeymoon in the house and the Earl resumed occupation of it soon afterwards.

Lutyens helped his new sister-in-law to bring Knebworth House into the 20th century. Knebworth, comprising only one wing of a vast Tudor quadrangle, the rest of which no longer exists, had been somewhat romanticised by Elizabeth Bulwer Lytton, who settled there in 1811; her son, Edward Bulwer Lytton, writer and politician, went the whole hog, by providing a fantastical skyline of barley-sugar chimneys, heraldic beasts and gargoyles. Lutyens judiciously culled the internal excesses, too heady for neo-Georgian taste or his own preference for aesthetic discipline. The gardens were also altered, although the house exterior was left as found.

Victor Lytton, however, still had to find a way of making his house, modernised in terms of taste, pay. As did many at the turn of the century, Lytton’s income from the land had suffered the pinch of the long agricultural recession that began in the 1870s — for an earl, the Knebworth estate had never been large. No wonder then, that the example of Letchworth Garden City, only 15 miles to the north, proved inspirational. There, Ebenezer Howard’s first garden city had begun to buy land in 1903, to fulfil his vision of a settlement where people could both live and work in the healthy surroundings of Nature. The first mention of Knebworth Garden Village was made in 1904.

Lytton did not immediately enlist his brother-in-law’s help: perhaps Lutyens had already acquired the reputation of being, in the words of a Treasury official attempting to block his appointment as designer of the British Embassy in Washington in the 1920s, ‘an extremely extravagant architect who doesn’t care what he lets his client in for’. But Lutyens had no qualms about reminding Lytton of his existence, by writing: ‘Your buildings proposed are horrible and very vulgar to look upon — do you mind this?’ (Fig 5)

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

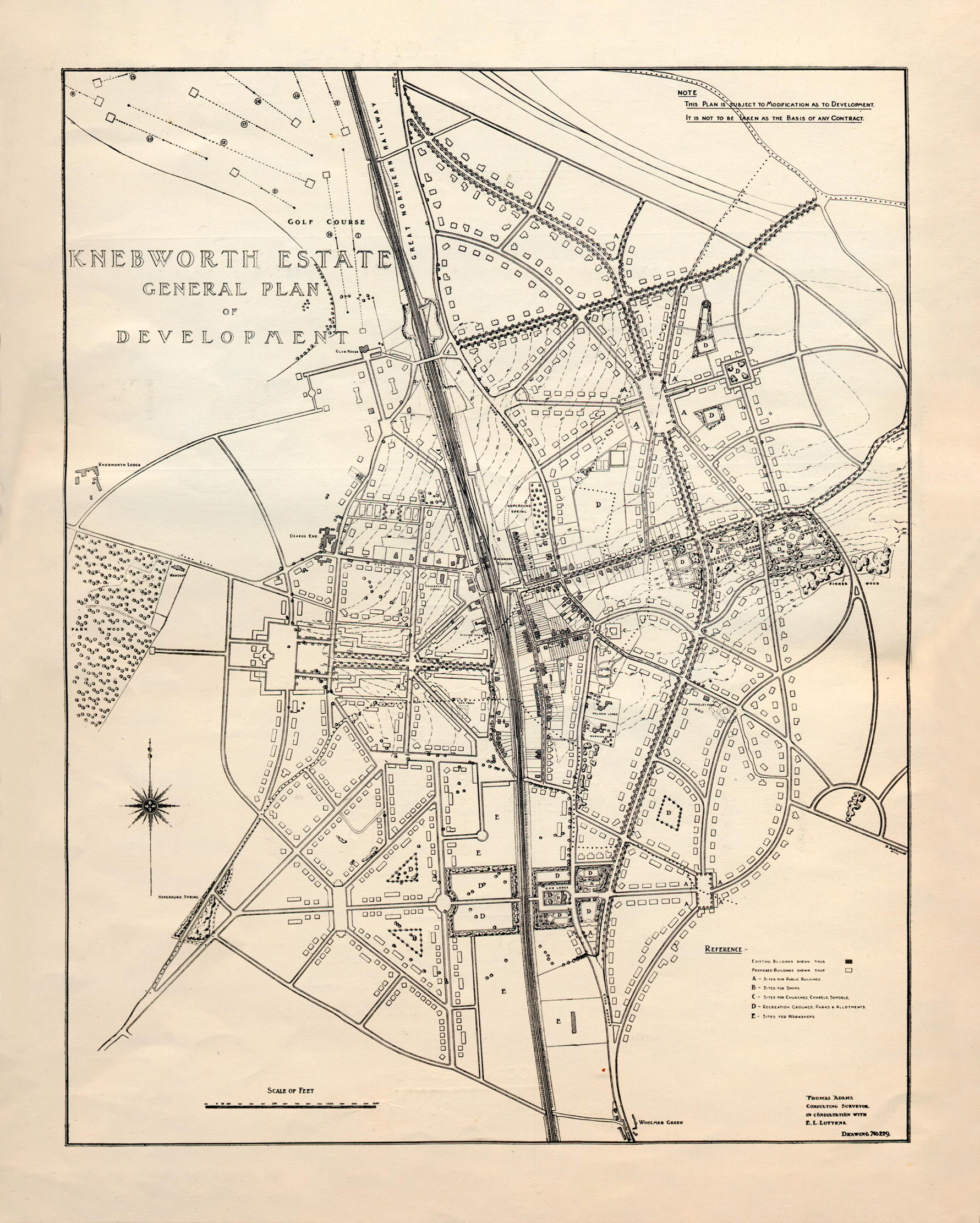

Lytton was evidently stung, because by the time the brochure announcing the scheme had been printed in 1911, Lutyens could be said to have prepared a ‘comprehensive scheme’ for the development of 1,000 acres, in conjunction with the planner Thomas Adams, who ran the development of Letchworth from 1903–06. It may be significant that the project’s long gestation came to an end the year after the passing of the Housing and Town Planning Act, which boosted the garden-city movement.

Whatever the case, by then Lutyens had been commissioned to design the focus of Hampstead Garden Suburb, Central Square, where he battled what he regarded as the faux rusticity demanded by Henrietta Barnett — whom he described to his wife as ‘proud of being a philistine, … [with] no idea much beyond a window box full of geraniums, calceolarias and lobelias, over which you can see a goose on a green’. The design of St Jude’s Church there was compromised as a result.

Given a genuinely rural site at Knebworth, however, his instinct was to regularise it with a geometrical pattern of straight, no doubt tree-lined roads, subsuming three ancient and meandering lanes (Fig 3). Still, it is noticeable that the promotional literature does not emphasise the formal qualities of the architecture, so much as the vision. The brochure’s cover (Fig 2) shows two children in a meadow, with a distant chimney and a gable — the only sign of habitation — poking through the trees. The first paragraph of the text trumpets the importance of ‘bright sunshine’, so much more abundant in rural locations than in smoke-ridden cities.

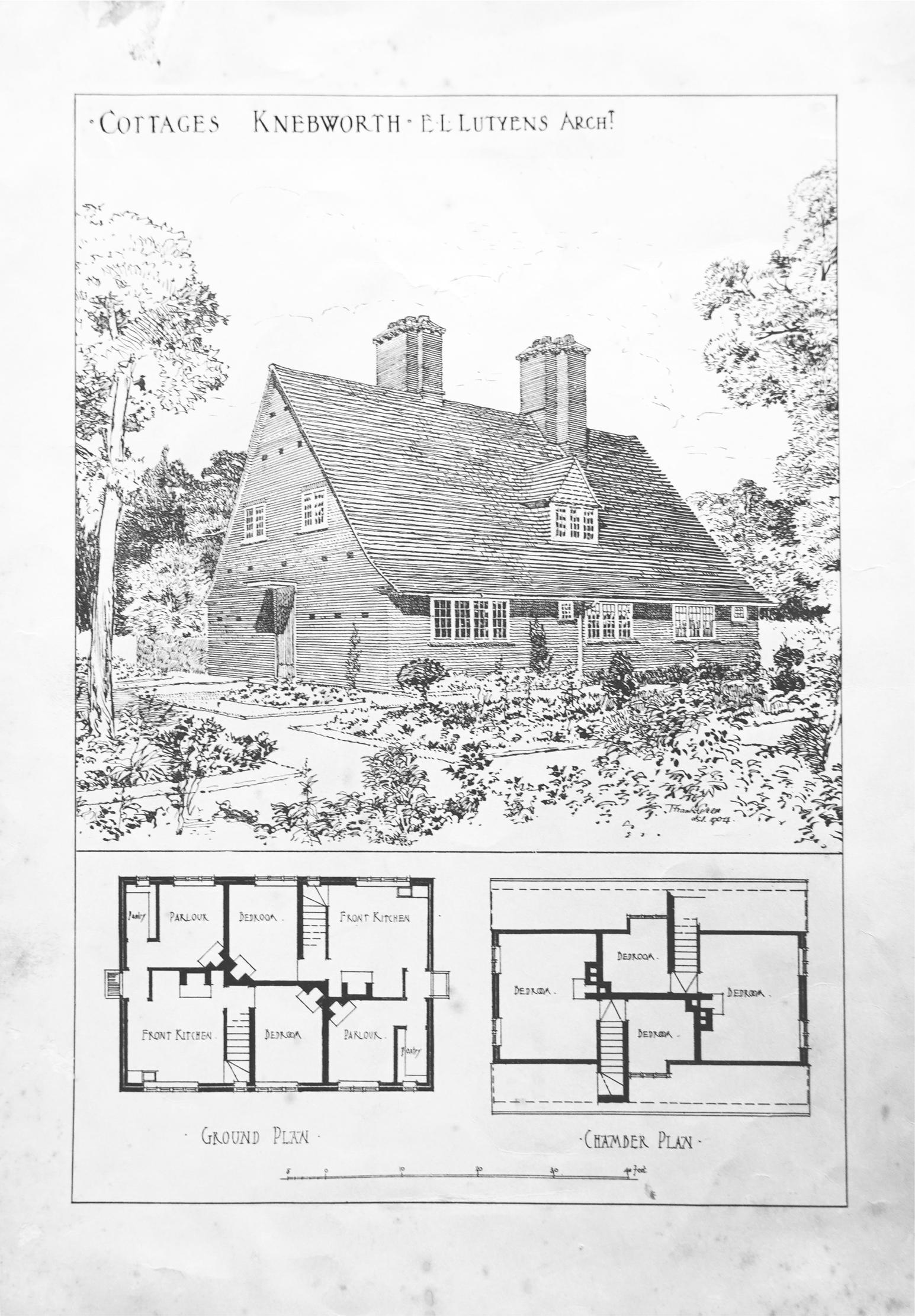

There were few pre-existing houses on this part of the estate, only three farms and a scatter of houses, often for railway workers, which had sprung up around the railway station of 1884. The new homes were to be set behind verges, hedges and generous front gardens (Fig 1). Although the years around 1911 were busy even by Lutyens’s hectic standards, he still kept an eye on the garden village. On February 16, for example, an assistant from Lutyens’s office wrote to Lytton, deploring a proposal to fill in a supposedly unhealthy pond: to do so would ‘spoil the character and colour of the surroundings’. Instead, it was observed, the problem could be solved by cleaning it out.

Four segments of the garden village had been built out by 1914. These survive substantially intact, with broad expanses of shared lawn and the houses, designed by Lutyens’s younger contemporaries, including his own son, Robert, set back behind hedges. Two of them — Stockens Green and Deards End Lane — are now conservation areas. Beyond the plan, Lutyens himself contributed a golf club house, in a countrified early-Georgian style, a twist being provided by a very deep roof with dormers and cupola; and the church of St Martin (Fig 4), a Greek cross within a square, very plain inside, but majestic from the use of two sizes of order, one of the arcades, the other at the crossing. The First World War brought building work to a halt. St Martin’s was hurriedly completed with a plain brick wall at the west end, rather than the intended portico, which remained until Sir Albert Richardson replaced it with a more appropriate design — with pediment, bell turret and three-light window — in the early 1960s.

In the difficult years after the First World War, the garden village languished; can this be explained by Lytton’s absence from England during the period 1922–27 when he served as Governor of Bengal? Estate maps show, however, that what had been built of the Lutyens scheme survived intact until the dark days of the 1970s, when some of the still-undeveloped areas were filled with the standard housing of the day. Infill continued, more intensively, during the 1980s. In 2019, a former builder’s yard on the high street, which might have formed an open nucleus for the settlement, became the site of a large retirement home; the arch into it is so low that ambulances cannot enter.

Yet the inhabitants of Knebworth today still prize the values of the garden village. This was loudly voiced in the meetings that have been held on numberless recent Wednesday evenings in the village hall during the compilation of several parish and local plans. These exercises in local democracy, which took place over many years, invariably reached the same conclusion: that local people like the green and open character of their surroundings, ultimately inherited from the Lutyens scheme. According to the brochure of 1911: ‘Lord Lytton determined that the development of his property should proceed only upon the very best lines and with due regard to the wellbeing of all who should reside there.’

His example has been followed by his successor at Knebworth, Henry 3rd Baron Cobbold, who has worked in concert with the equally exemplary Wallace family, farmers who bought some of the land sold from Knebworth to pay for death duties in the 20th century. They both prepared carefully researched design guides for the development of three sites on the edge of the garden village that were allocated for building when the North Herts Local Plan 2011–31 was eventually approved in 2022. Alas, the planning winds have now changed. Rather than localism ruling the day, the final word goes to design-review panels of unelected outsiders. The pro-garden-city sentiments of the 2010s have been replaced by a desire to increase the density of population and discourage car use.

These may be worthy objectives in towns and cities, where they tend to promote community interaction and reduce the carbon emissions, but are not necessarily appropriate in the countryside. True, Knebworth has a railway station, but not every journey will be made to places that can easily be reached by rail. The elderly of the village will not find it easy to bicycle to the nearest superstore, particularly given the hilly character of the topography.

Knebworth Garden Village — New Knebworth, as it became known — is not a settlement in search of an identity; it already has a unique one, thanks in part to Lytton and Lutyens, but also given its location in Hertfordshire, a cradle of the garden-city movement. Admittedly, this has been degraded in parts, but it would be surely better to build on the legacy that exists rather than seek to replace it with a new personality, based on today’s planning nostrums.

Cars may be regarded as the Devil’s work, but is it really wise to insist on a busy settlement using only the ancient lanes that existed before New Knebworth had been born? Or to build new schools without any provision for parents to drop off their young? Hedgerows have come to be regarded as sacrosanct, when any countryman knows that many can be easily re-laid, with little detriment to wildlife or species diversity. Meanwhile, proper planning — as exemplified by Lytton’s garden village — is allowed to go hang. To adapt Lutyens’s words, the planners will soon have made New Knebworth horrible to look upon. Do the councillors of North Hertfordshire mind this?

Historic Houses president Martha Lytton Cobbold: 'We aren’t looking for special treatment, simply an equal playing field'

The new Historic Houses president talks to Teresa Levonian-Cole about leaky roofs, lobbying Government and VAT.