My Favourite Painting: David Linley

David Linley chooses his favourite painting for Country Life.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

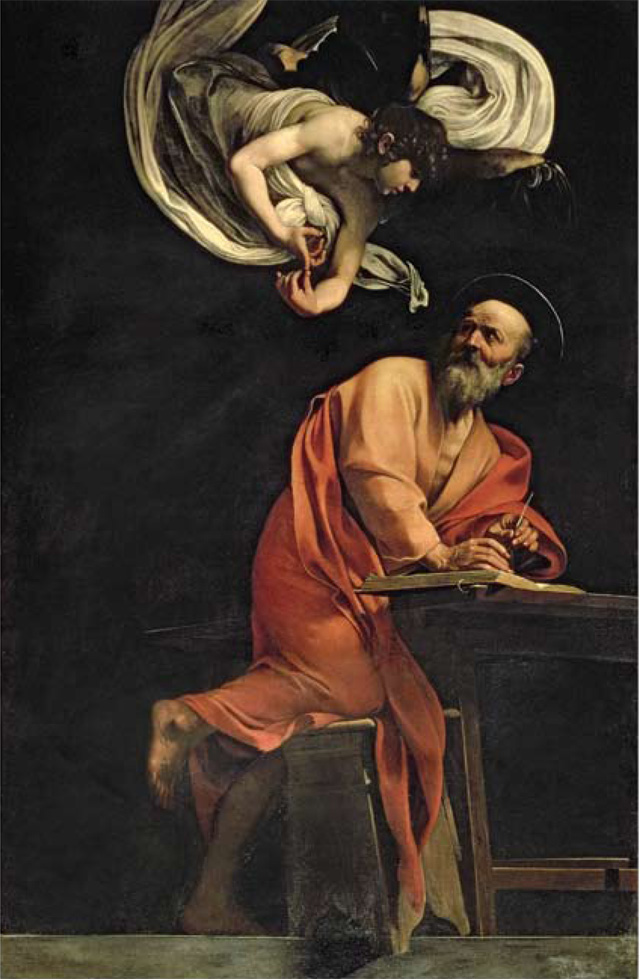

St Matthew and the Angel, 1602/3, 116in by 77in, by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571–1610), San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome. Bridgeman Images.

David Linley says: ‘I first saw this painting when I visited Rome with my mother and sister in my mid twenties. As with the furniture I admire, I was immediately drawn to the simple and strikingly modern composition. One is struck by the serene design, the masterly use of colour and acute observation to create such realism with dramatic light effects. Such an exceptional work is an example of Caravaggio’s great craftsmanship and skill in fooling the eye with the projection of the scene into our space.’

Viscount Linley is a furniture designer, founder of Linley and chairman of Christie’s UK.

Art critic John McEwen comments: 'In the Orthodox Church, strict rules still govern the depiction of sacred subjects. In the western Church, these rules slackened long ago and, with the Renaissance, the confines of icon painting were totally abandoned as artists brought sacred imagery down to earth in every sense. No one did this more audaciously than Caravaggio, whose sacred pictures emphasise ordinary humanity to the point of costume drama.

The degree to which he pushed this new-won freedom caused the rejection of his first picture of St Michael and the Angel for the Contarelli Chapel in San Luigi. It showed a scruffy, apparently barely literate St Matthew being helped to write his gospel by a young angel, who leans over his shoulder to guide his hand across the page. The result was deemed irreverent and unbecoming. It was, nonetheless, a notably gentle and compassionate image in Caravaggio’s invariably dramatic and sometimes shockingly violent oeuvre. The picture was destroyed in the Second World War, having finished up in a Berlin museum.

This is Caravaggio’s more acceptable second version. St Matthew is no longer a scruff. He wears sumptuous robes and has a noble demeanour, and the angel, a handsome boy, doesn’t guide his hand, but dictates the holy words. Matthew’s Gospel begins with a recitation of Christ’s genealogical descent from Abraham down to Joseph. This is the moment depicted, the angel numbering Jesus’ forefathers on his fingers. In accordance with a more elevated, less intimate, interpretation of the subject, the angel is not casually posed, but descends from heaven.'

This article was first published in Country Life, March 23, 2011

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.