Carla Carlisle: The enduring search for Sir Ernest Shackleton's Endurance

When Carla Carlisle discovered that her path had crossed that of Sir Ernest Shackleton — albeit many years apart — it triggered a lifelong fascination with the explorer, his crew, his ship and his official photographer.

Editor's note: Just a day after we originally published this column, the news broke that Shackleton's ship has indeed been found. 'We have made polar history with the discovery of Endurance, and successfully completed the world’s most challenging shipwreck search,' said expedition leader Dr John Shears after the wreck's discovery 3,008 metres below the surface of the Weddell Sea. The wreck is said to be in an extraordinary state of preservation thanks to the extreme cold which has prevented microorganisms from decaying the timbers.

'This is by far the finest wooden shipwreck I have ever seen,' said Mensun Bound, the expedition's director of exploration. 'It is upright, well proud of the seabed, intact, and in a brilliant state of preservation … This is a milestone in polar history.'

Read more at the BBC or The Guardian.

I am sitting at my desk in a Suffolk manor house that is a collage of dates: 1585, 1640, 1920. All the places we’ve ever lived have a way of imprinting our lives. I was born on the banks of the Yazoo — Choctaw for River of Death. It’s a good name for a muddy tributary of the Mississippi that is deadly when it floods, deathly when the flat land surrounding it reaches 100 degrees at dawn.

My legacy from this land of heat, cotton and copperheads? A lifelong yearning for… snow. A love of the world of white-on-white that I knew only through photographs, movies and books.

Another place that enriched my nomadic life was Putney Heath. The friend who introduced me to the man who installed me in this manor house, coached me: ‘Don’t go on about how much you love Putney. It sounds so suburban,’ but I loved the flat carved out of the first floor of an Edwardian house. Five days after I moved in, the blizzard of December 1981 transformed my new universe. It was a sign. Before the snow had melted I learned that, from 1911 to 1913, Ernest Shackleton, his wife Emily and their three children had lived in my house.

Not that I knew a lot about the heroic polar explorer when I arrived at No 7, Heathview Gardens. I knew North was the Arctic (polar bears) and South was Antarctic (penguins, no polar bears). In Mississippi, a land half-in love with defeat, it was Robert Falcon Scott who was revered.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

English, courageous, a lover of Russian novels and the poetry of Tennyson, he was the tragic hero who, in 1912, reached the South Pole 34 days after Amundsen planted the Norwegian flag in the snow. Two months later, Scott and what was left of his gallant team pitched their second-rate tent, tucked themselves into their reindeer-hide sleeping bags and entered the sleep that polar explorers know will be their last. The most heart-breaking part of the story? They were only 11 miles from One Ton Depot, with its plentiful supplies.

"What I had not counted on was discovering how close a man could come to dying and still not die, or want to die"

The other arctic explorer we learned about was the American Admiral Richard Byrd. The first person to fly over the North Pole and, later, the South Pole, it was the five months he spent alone in a one-room underground shack in Antarctica in 1934 that fascinated me. One summer, I found a copy of ‘Alone’, Byrd’s account of that journey.

He believed he would spend his time reading and listening to classical music on his wind-up record player, but, a month in, he realised the fumes from his oil-burning stove were poisoning him. 'What I had not counted on was discovering how close a man could come to dying and still not die, or want to die,’ he wrote. Read enough memoirs of polar exploration, including Ranulph Fiennes, and you realise it is a sombre theme.

Shackleton and his epic journey across the treacherous Weddell Sea soon became my obsession. He is also at the centre of the modest, if unlikely, polar shrine in this manor house.

I have more than 40 books on polar exploration, including maps, journals and photographs. On the sitting-room walls are 10 ‘museum quality’ photographs by Frank Hurley, official photographer of the Endurance expedition. I live with his legendary images: Endurance strangled by ice, the men pulling the open boats over land, and the dogs, the dogs who trusted the men who led them into this white danger (that story is too sad to tell here).

Every evening, I log on to follow another expedition. A century after Endurance was crushed by ice and sank, a state-of-the-art South African icebreaker, Agulhas II, with a crew of 46 and a team of scientists, has gone in search of her. Financed by an anonymous donor at a cost of more than $10 million, Endurance22 has only two weeks and two underwater drones to locate and survey the lost ship which is sitting in 10,000ft of water in what Shackleton described the ‘worst sea in the world’.

I follow Endurance22 in various podcasts. Tonight, the icebreaker is stranded in pack ice just like Endurance, a reminder that ice is a brutal dictator that doesn’t respect tenacity, courage, modern technology and science. The marine archaeologists think they are close to the right spot—give or take a few miles—based on the calculations of the ship’s captain, Frank Worsley, who Endurance obsessives believe was the real hero of the greatest survival story in exploration.

The $10 million cost of the expedition also stayed in my mind. In my nightly tracking of Endurance22, I began searching for a photograph of the Putney house when Shackleton lived there. I found mention of it — Shackleton, always on the edge financially, worried the house added to his woes — but no family photo. Instead, I discovered that the house is for sale. Turned back into a single dwelling, it now sits behind two imposing gates and a high fence. It has the whiff of oligarchy about it, including a swimming pool and pool house in the garden where I once planted tree peonies that were beyond my means. The price tag is almost exactly the cost of the Endurance22 expedition.

One thing gives me peace of mind, however. If Endurance is found, the drones will take photographs and make laser scans of the wreckage, but the site won’t be disturbed. It was declared a historic monument under the terms of the Antarctic Treaty signed in 1959 ‘to preserve the continent for peaceful purposes'.

I wish I could say the same for my — and Shackleton’s — old house. You might think its significance is emotional, not historical, but I believe one of those round blue plaques would have been a more valuable addition than a swimming pool.

Sir Ernest Shackleton's former home in Putney is up for sale, and it's a home fit for a hero

Ernest Shackleton swapped this beautiful home in a leafy London suburb for the bleak conditions of the Antarctic.

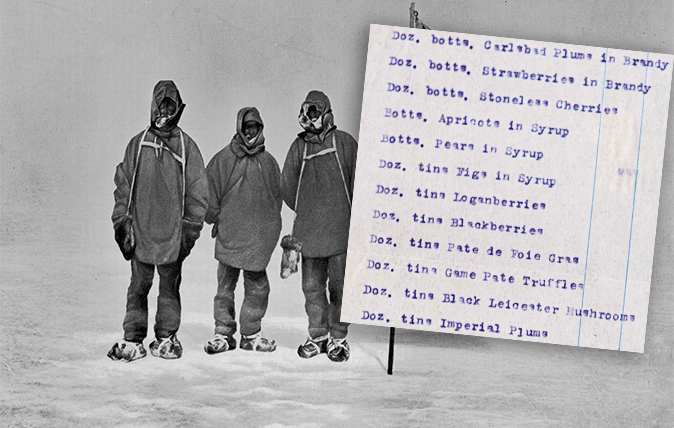

Ernest Shackelton’s arctic shopping list, and other secrets of Britain’s great shops

Harrods, Fortnum & Mason and most of Britain's other great retailers have archivists – and they shared some of their