Carla Carlisle: 'You don’t need a map to tell you that East Anglia and Russia are closer than they look'

'It was like a Tarantino movie where the bad chase the bad,' says our columnist Carla Carlisle as events in Russia consume her attention.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

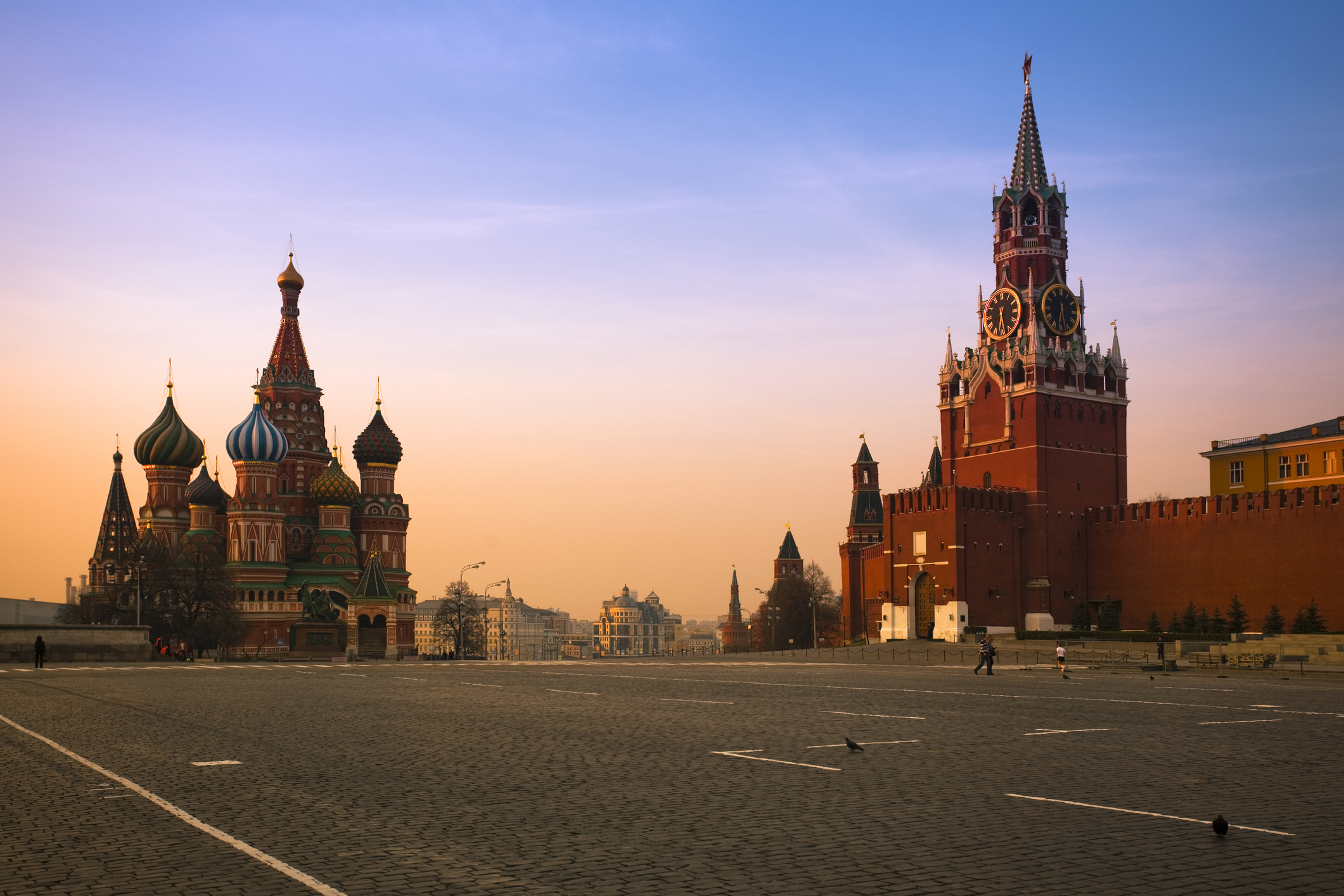

My first English Christmas was spent in Cambridge. The carol service at King’s College Chapel. A heavy snowfall. Icy grandeur. It was beautiful. It was cold. ‘There is nothing between the flat lands of East Anglia and Siberia except Ely Cathedral,’ my Cambridge friends told me. I’ve now repeated that many times. Unlike Sarah Palin, I can’t see Russia outside my bathroom window.

My husband says that showing me a map is like taking a labrador to an art gallery. When I look at the Times World Atlas for the ‘nothing between’ this flat patch of Suffolk and Russia, I see a 1,000-piece picture puzzle of land and sea. And yet, for 24 hours last week, we listened to the radio, watched the news on television and read the newspapers as if Russia was just beyond Norfolk.

It was like a Tarantino movie where the bad chase the bad. At first we wanted Putin to lose to the murderous mercenary from St Petersburg who turned a catering company into the world’s largest private army. Then we remembered: Prigozhin would be worse.

Map reading is not my only geographical limitation. ‘Good god! They are closer to Moscow than Bury St Edmunds is to London!’ I cried, when the reporter announced ‘120 miles from Moscow’. I stared at the rolling convoy. Then, suddenly, the Tarantino movie turned into Wes Anderson, more The Death of Stalin than The Grand Budapest Hotel as the most battle-hardened part of the Russian army turned around. This was not a break for lunch before the coup, but a long day’s journey into exile in Belarus. Or somewhere. Nobody really knows.

On the his-and-her bookshelves in this house is a Russian library. His include Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Turgenev, Chekhov — the great Russian writers Before the Revolution. Mine are After the Revolution, filled with volumes by writers and poets who died tragically early, committed suicide or perished at the hands of the state — Akhmatova, Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva, Pasternak, Nabokov, Brodsky.

I don’t like to admit that my passion for these writers began with Doctor Zhivago — the movie. No one has ever mistaken me for Julie Christie, although I’ve dressed in Russian-style hats and coats since 1966. The legacy I admit to: the book. After I saw the film, I read the novel. I then read everything by and about Pasternak in print, including the writers who were his friends. That’s how I found the poet Marina Tsvetaeva.

"These aren’t political exiles: they go back and forth, complaining only that travel to the US and the UK now involves flying to Dubai and changing planes"

I read the Russians in English. I’ve been to Russia only once, a small ‘cultural’ tour described as ‘St Petersburg: Pictures and Palaces’, led by a Russian specialist from the V&A Museum. The city was still emerging from its long Soviet dormancy and western hotels, Michelin-starred restaurants, Chanels and Burberrys were opening. The black-and-white world of John le Carré was history.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

On the second day, I defected from the palaces and made my way to the apartment in Fountain House, where the poet Anna Akhmatova lived from 1923 to 1952. An ‘internal emigree’, she was unable to publish any poetry between 1925 and 1940. One day, she was visited here by Isaiah Berlin, then a diplomat at the British Embassy in Moscow. He was a rare and precious contact for the poet, but, soon after their meeting, she was branded an ‘enemy of the people’.

The next day, I managed to find the Nabokov Museum, the three-storey house on an elegant street where the writer and lepidopterist was born in 1899. Two years after the Revolution in 1917, the house was seized by the Red Guard and the Nabokov family emigrated from Russia, never to return. I was the only visitor and the sole guard asked if I wanted to see ‘the English film’. I then spent an hour watching a film made by the BBC in 1962 as the guard sat motionless in the doorway.

I felt I knew the house from Nabokov’s achingly beautiful memoir Speak, Memory. These were the rooms of the perfect childhood: a much-loved child of sensitive, cultured parents in St Petersburg, a bewildering sequence of English nannies and governesses, Pears Soap, Golden Syrup and blazers. He could speak and write in English before he could speak Russian, a fluency that served him well in his life of exile, beginning in 1919 when he was admitted to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied Zoology before changing to Slavic and Romance languages. He skipped lectures, read King Lear and Ulysses, translated Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and poems by Rupert Brooke into Russian and decided to become a writer.

Watching the coup-that-wasn’t awakened my own Speak, Memory. For days following the invasion of Ukraine, I felt fury at the Russians who are proud of Putin and his kleptocratic clique, who admire Prigozhin and his army of mercenaries. My anger grew. No, the Russian ballet/opera/musicians shouldn’t perform here (I forgot about Nureyev). More rage: a friend in Nice tells me that ‘you now hear more Russian here than French’. The Russian diaspora likes warm climates: Israel, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Florida. These aren’t political exiles: they go back and forth, complaining only that travel to the US and the UK now involves flying to Dubai and changing planes.

Then I remember the Pussy Riot collective who staged a protest against the regime of Putin. I see Navalny sitting in a glass box during his show trial. I think of Anna Politkovskaya. Two years after she published Putin’s Russia, she was shot dead in the elevator of her apartment building in Moscow. Who does not wish that Navalny was in California with his daughter?

Last year, we raised funds for the Halo Trust in Ukraine. The would-be mutiny is a reminder to start again. You don’t need a map to tell you that East Anglia and Russia are closer than they look.

Carla Carlisle: 'Who thought visas that will expire on Christmas Eve was a good idea? The sooner they delete Bing Crosby’s I’ll be home for Christmas from the Department for Transport playlist the better'

Carla Carlisle does her very, very best to stay positive — and just about pulls if off.

Credit: Getty Images

Carla Carlisle: 'I’m about to expand on my belief that reading fertilises our memories and allows us to visit our past without getting hurt when I see her eyes wander off towards Monty Don'

Books create a powerful connection with the home of your youth, finds Carla Carlisle.

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle: 'We took it for granted that we could travel the world and live wherever we wanted... Now the dice is loaded against our children and against the planet. What were we thinking?'

Carla Carlisle on being a pessimist, making lists, and seeing snow for the first time.

Carla Carlisle: 'I felt a surge of gratitude and hopefulness that’s hard to describe. You could call it Thanksgiving.'

A visit to St Paul's Cathedral provokes a flood of feelings in Carla Carlisle.

Credit: Alamy

Carla Carlisle: 'There are decades when nothing happens and weeks when decades happen'

Carla Carlisle on how she brightened her Christmas with music, the perfect balm in stormy times.

Credit: De Agostini via Getty Images

'It took my son and daughter-in-law a weekend to set up an online shop... In a week, we sold £10,000 of wine that was languishing in the bonded warehouse'

Carla Carlisle's lockdown has taken her farm shop to places she'd never imagined — but now she's there, she's not