The stories behind the strangest phrases in English from being 'gone for a burton' to 'caught red-handed'

Learning a language is one thing, getting to grips with a pig in a poke is another altogether. Octavia Pollock explores some of our best idioms

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The world and his wife are fond of touching wood to avoid a spanner in the works or, as the Americans have it, everyone and his mother knock on wood to prevent a wrench in the works. In England, we take French leave; across the Channel, they filer a l’anglaise. Idioms exist everywhere, stemming from the Bible, from farming, sailing, games, superstition, war, literature and any other sphere of human influence. You might know your onions and get off scot free or you might be taken aback and find yourself blotting your copybook. Before you’re befuddled by bits and bobs, here’s a baker’s dozen of the best.

1. Casting pearls before swine

Miss Piggy in her pearl necklace might object, but, according to Jesus in the Gospels, ‘neither cast ye your pearls before swine, lest they trample them under their feet’. Don’t waste your time baking a three-tier illusion cake for someone who’d rather have a Krispy Kreme doughnut — save it for your Great British Bake Off audition.

2. It’s all gone pear shaped

Sweet and delicious they may be, but if you’re wanting a glass ball or a soaring aerial circle, a pear is decidedly unwelcome. Whether it originated from over-heated glass blowing or RAF pilots getting a bit flat when looping the loop, this is one phrase no one wants to hear.

3. Buy a pig in a poke

Bustling and crowded, silver jingling in purses and pick-pockets darting every which way, marketplaces are where the grifters and the gullible mix. If you failed to open the poke — or bag — to inspect your squirming piglet, you might get a nasty surprise. Be grateful if someone lets the cat out of the bag, although, if you’re on a ship and the bosun draws the cat o’ nine tails from its red cloth, watch out.

4. The devil to pay and no pitch hot

Being caught between the devil and the deep blue sea is no place to be, when the devil is the longest seam of a ship, deep and difficult to get to. To keep deck seams watertight, sailors had to caulk, or pay, them with hot tar, or pitch, or risk an encounter with Davy Jones. William Langland has an older claim on paying the devil, however, as the phrase appears in Piers Plowman, centuries before the first man o’ war was laid down.

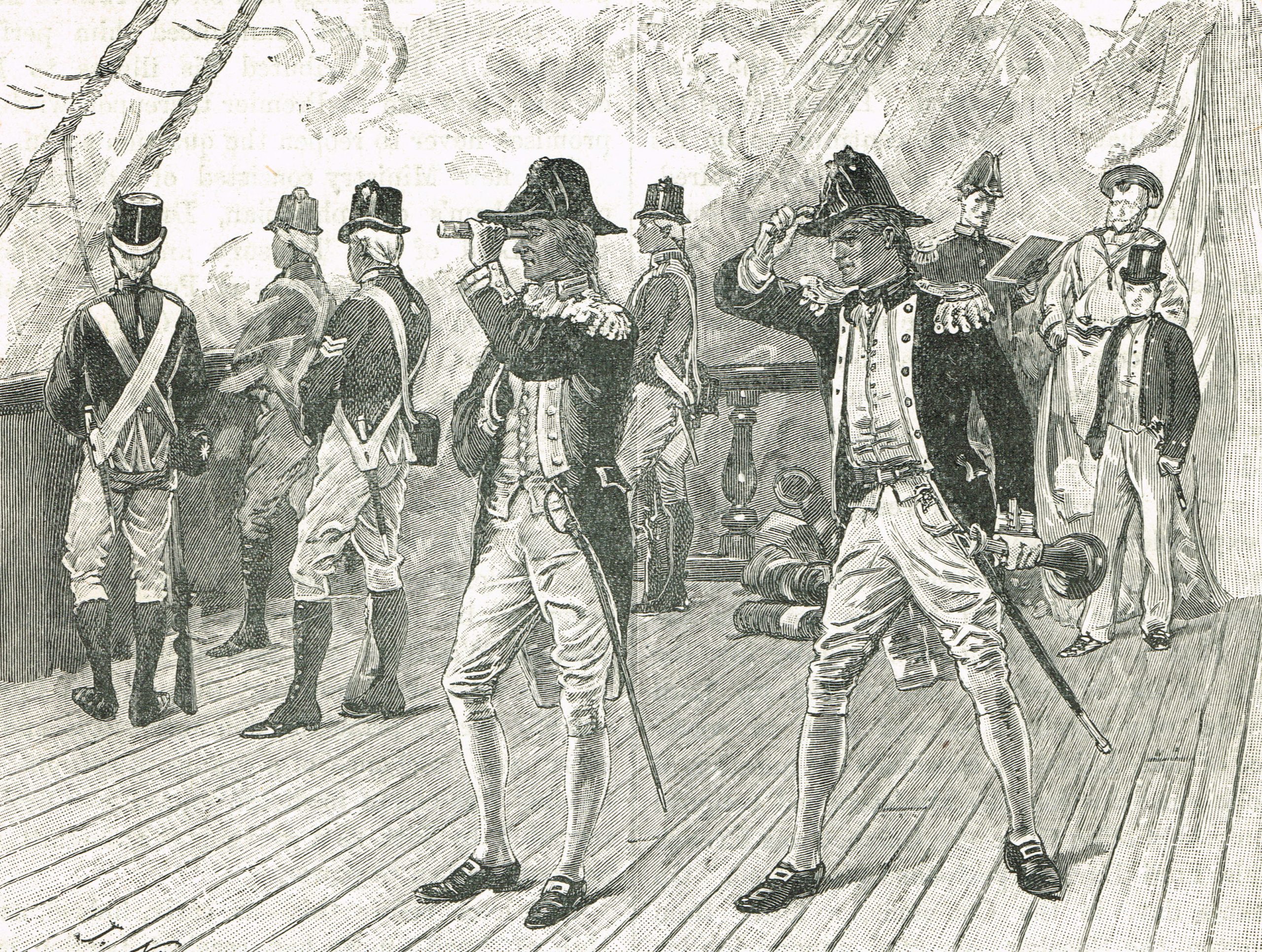

5. Turning a blind eye

Our greatest naval hero was not averse to using guile with his friends, as well as his enemies. Disagreeing with Admiral Sir Hyde Parker’s order to retreat at the Battle of Copenhagen, Nelson viewed the signal flags with the telescope to his blind eye, famously declared to the ship's company 'I see no ships,', then pushed on and won the day.

6. Steal someone’s thunder

In the wings of the theatre, a stagehand might lurk, out of the limelight, with the flexible sheet of tin shaken to emulate thunder at dramatic moments. John Dennis invented the device in 1709 for his play Appius and Virginia, which closed soon after it opened. Perhaps it was his chagrin at its failure that led him, on attending a performance of Macbeth in which they used his effect, to exclaim: ‘They will not let my play run and yet they steal my thunder!’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

7. Win hands down or by a long chalk

We’d all like an effortless win now and then, when we can canter across the finish line without ever having gathered the horse together or raised our whip hand. It’s also satisfying to see the score being steadily marked up with ever-longer chalk marks, much less stressful than being neck and neck down to the wire.

8. Caught red handed

Fieldsports have given us countless common phrases; how many MPs realise that their parliamentary whips echo a hunt’s whippers-in? Many are literal, including beating around the bush (to put up birds). A poacher who had successfully shot a deer would do the gralloch — in other words, disembowelling the unfortunate creature — before taking off with his prize. This stationary period would give a gamekeeper time to catch him with hands scarlet from the blood.

9. Wear your heart on your sleeve

A knight on his high horse had no qualms about revealing a tendre for a particular lady as he lined up for the joust. Indeed, he would display her favour, perhaps a ribbon or handkerchief, prominently. Tying it to his arm would be the obvious place and, if he won his bout, he might win her heart, too.

10. Gone for a burton

The beer of Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire led to this RAF euphemism for giving up the ghost: such was the quality of the town’s ale that pilots who didn’t come back were deemed, with wartime black humour, to have chosen a pint over reporting for duty.

11. Worth your salt

The stem of ‘salt’, sal, reveals the origins of this phrase: the Latin for salary. In Roman times, salt was so valuable it was sometimes distributed instead of money. ‘Earning your salt’ would meet with Jesus’s approval: in the Sermon on the Mount, he called his followers ‘the salt of the earth’.

12. Tar with the same brush

Sheep today might sport all kinds of colourful hues at lambing time, but a lonely goatherd or shepherd in times past was more restricted when it came to marking his herd, with only sticky tar to hand. Let’s hope he never cried wolf, or he might have found himself a lamb to the slaughter.

13. He who pays the piper calls the tune

If you want to be in control, pay your dues or beware… when the Mayor of Hamelin refused to pay the Pied Piper, all the children of the town were lured away. Or, more prosaically, if you’re the laird of a castle holding a grand ceilidh, you can choose to bump bottoms in Strip the Willow or practice your one-handed press-ups in the Eightsome circle.

Curious Questions: Who invented tennis?

It's 150 years since the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club was formed – though originally it was solely for

Curious Questions: Should animals wear clothes?

Martin Fone, decidedly not an animal person, ponders whether animals should wear clothes and, indeed, what a stylish pet would

Carla Carlisle: 'It sounds tactless, but I’ve long believed that the most beautiful word in the English language is "cancelled"'

Raging against the lockdown isn't for Carla Carlisle, as she admits to 'a swoosh of contentment' whenever she thinks about

Octavia, Country Life's Chief Sub Editor, began her career aged six when she corrected the grammar on a fish-and-chip sign at a country fair. With a degree in History of Art and English from St Andrews University, she ventured to London with trepidation, but swiftly found her spiritual home at Country Life. She ran away to San Francisco in California in 2013, but returned in 2018 and has settled in West Sussex with her miniature poodle Tiffin. Octavia also writes for The Field and Horse & Hound and is never happier than on a horse behind hounds.