Curious Questions: Why did people used to wash clothes in urine?

An experience far from home prompts Martin Fone to delve into the history of laundry — including the rather unpleasants secrets of removing stains.

Visiting a laundrette is not normally high on my list of must-see tourist sites but whilst in Kerala I was persuaded to visit the Dhobi Ghat on Kochi’s Veli Street, a communal laundry run by around 40 families, providing services to houses, hospitals, and hotels in the area.

What I saw was astonishing.

A flick of an accomplished wrist brought the garment, sodden from the waters of the river, hard down on to a huge flogging stone with a resounding crack. It was then rinsed in tap water and starched, cotton items in rice water and others in a boiled sago-based solution with a dash of perfume. Drying took place in the serried rows of washing lines in the compound’s three-acre site. Finally, the items were ironed using a heavy, antediluvian flat iron to a crisp, creased perfection.

It was a hive of industry and it all looked phenomenally hard work. Heavily weather dependent — incomes drop dramatically during the monsoon season — it is about as far removed from our modern washing experience as you could imagine.

I realised, though, this was how our ancestors had done their laundry for centuries. Garments would be washed in the river, beaten over rocks, scrubbed with abrasive sand or stone to remove marks and stains, and generally assaulted underfoot or pounded with wooden implements. Edward Burt, whilst travelling in northern Scotland in 1754, noted in a letter; ‘commonly to be seen by the sides of the river… in all parts of Scotland where I have been… women with their coats tucked up, stamping, in tubs, upon linen by way of washing.’

Burt’s inference, though, was that this practice was now unusual in England. With populations increasingly moving from rural to urban settings, the riverbank, feet, and rocks had been replaced by large wooden washtubs and tall tubs, known as dolly-tubs or possing-tubs, in which a plunger was used to beat and stir the clothing.

One of the most pressing problems, in the absence of soaps and detergent, was how to remove stains, dirt, and grease. The Romans discovered an effective stain-remover: human urine with its high ammonia content. Urine-based cleaning agents, euphemistically known as ‘chamber lye’, were used well into the 19th century. In a process known as ‘bucking’ the items were placed in the bottom of a tub – you will be relieved to know they had a separate bucking tub especially for the task – and cheesecloth or some porous material was put over the top. The lye, once warmed, went on top of the covering and hot water poured over it, a process which was repeated several times. This meant, of course, that the lye had to be reheated each time.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In The Complete Chamber Maid (1677), Hannah Woolley described how to deal with particularly obstinate stains with a sequence to be carried out prior to washing the item:

‘Lay it all night in urine, rub all the spots in the urine as if you were washing in water; then lay it in more urine another night and then rub it again, and so do until they [stains] be quite out.’

A time-consuming, not to say unpleasant and laborious, process, even before you even got to clean, rinse, and dry the garments. With drying in the temperamental English climate a protracted and precarious undertaking in its own right, a wash was not something to be considered lightly.

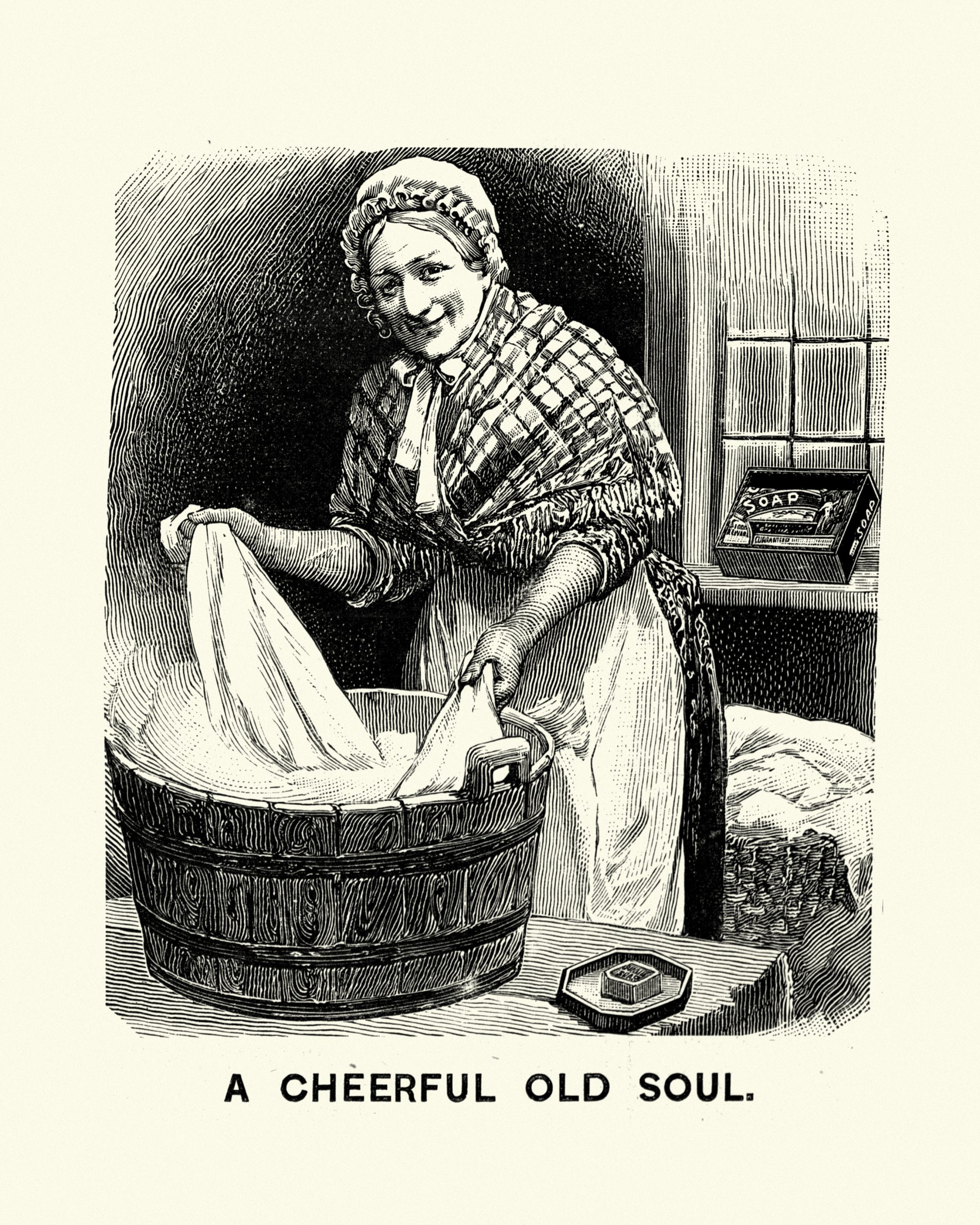

Those who could took great pride in having a large supply of linen that would tide them over for a few weeks, before what Hannah Glasse, the Mrs Beeton of Georgian England, described as a ‘great wash’ took place. Often a professional washerwoman was employed to take care of the heavier aspects such as washing and wringing out the sodden linen.

Flora Thompson, in Candleford Green (1945), a charming novel set around 1890, described the village postmistress, Miss Lane, who ‘still kept to the old middle-class country custom of one huge washing of linen every six weeks… the better off a family a family was, the more changes of linen its members were supposed to possess, and the less frequent the washday’. She hired a washerwoman, who left after the second of evening of washing with her fee of three shillings, the rest of the week spent by the family in ‘sprinkling, mangling, ironing and airing the clothes’.

Miss Lane may have been a relic from the past. Anna Cummings Johnson, in her Peasant Life in Germany (1858), suggested that by the mid-19th century even the Germans had moved away from a large, infrequent wash to one done ‘every two weeks, exactly like the English and Americans’. For many families, though, a large supply of linen was a luxury they could ill-afford and more regular washing days were a necessity.

Even so, they liked to keep up appearances, dividing their apparel between weekday clothing and ‘Sunday best’. Despite involving fewer, but perhaps more soiled, garments, a wash was still an involved and time-consuming process. The water had to be heated, whites and coloureds washed separately, agitated using a dolly plunger or a washboard, rinsed, mangled and, for certain items, starched, before being hung on a line to dry. Starting the process early on a Monday morning, often around five or six in the morning, maximised the opportunity to have their Sunday best ready for the following Sabbath.

An aspiring housewife, wondering how to organise her week, could find guidance from this 19th century piece of doggerel:

‘Wash on Monday Iron on Tuesday Mend on Wednesday Go to market on Thursday Clean on Friday Bake on Saturday Rest on Sunday.’

So popular was the rhyme that it gave rise to a set of Day Of The Week tea towels, usually six, a seventh being deemed unnecessary for a day of rest, each telling the housewife what she should do that day. The irony that they added to her laundry burdens was, doubtless, not lost on her.

Nursery rhymes were always a good way of reinforcing standards of expected behaviour. Halliwell’s Nursery Rhymes of England (1842) contained this gem, highlighting the perils and time pressures associated missing the Monday wash:

‘They that wash on Monday Have all the week to dry; They that wash on Tuesday Are not so much awry; They that wash on Wednesday Are not so much to blame; They that wash on Thursday Wash for shame; They that wash on Friday Wash in need; And they that wash on Saturday Oh! they’re sluts indeed.’

There were other reasons for washing on a Monday. As the laundry process was so protracted, all other household chores went by the board that day. There was no time to prepare a meal — the master of even the poorest house would consider it beneath his dignity to cook dinner — but, fortunately, there would often be leftovers from the Sunday meal. These could be served cold on a Monday evening without incurring the husband’s wrath. Also, in industrial towns, Sunday was a day of rest even for the factory chimneys belching out plumes of foul smoke. The air was at its cleanest if you hung your washing out on a Monday morning. It made sense.

Nowadays washing is relatively easier and is done whenever we want, tumble dryers aiding the drying process. It is worth a moment’s reflection, though, on how far we have come.

Credit: Alamy

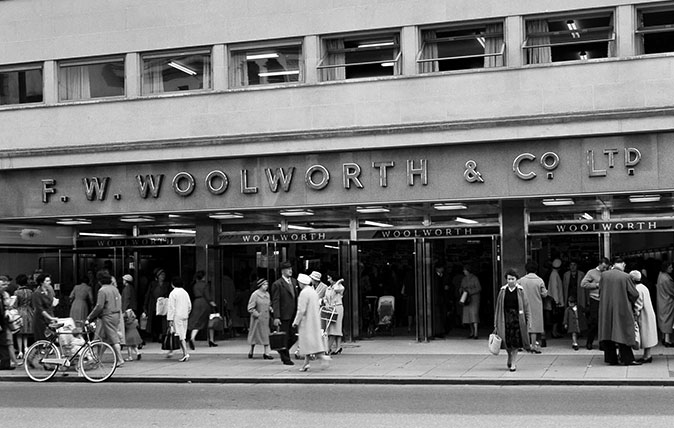

The day that Woolworths accidentally sold me an endangered species

Charles Quest-Ritson reminisces about the day his bargain purchase of a cyclamen in Woolworths proved to be something rather special.

Credit: Getty Images/EyeEm

Jason Goodwin: The night I accidentally sent a friend to go dogging on a remote West Country hilltop

Oh, Jason. It could have happened to anyone.

Credit: Andrew Barwick / Getty

A farmer in Norfolk has accidentally turned one of his fields into an entire field of sunflowers

Fakenham sugar beet grower Robert Hambidge added 'a few more' seeds to his mix and ended up with a vast

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.