Jason Goodwin: ‘Memories fade. Gavin was right: buildings outlive us all and they’re each memorials. They should not be allowed to disappear’

Our columnist remembers Gavin Stamp, the architectural critic, historian and campaigner.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Years ago, when we were young and free, we drove a former Post Office van and had a lurcher called Dorrit, who went to all the parties we were ever asked to. Coal-black and soft as gloves, she would lie on the floor in her Appenzeller collar, looking mightily bored by the conversation and, if it was that kind of a party, the photographer would always snap her. The next day, her picture would appear in the paper with a caption such as ‘An unimpressed guest’ and our hosts would be duly and understandably annoyed.

Dorrit went everywhere, as did the van – to Prague, the Hebrides, the Pyrenees and Glasgow, where, one evening, we went to hear Gavin Stamp give a brilliant, moving talk about war memorials, including the Menin Gate and Lutyens’s Memorial to the Missing of the Somme at Thiepval. It was long ago and not long enough, for the other day, at St Giles’s, Camberwell, we attended his funeral.

If you appreciate good building and mourn the destruction of historic architecture, you will have heard of Gavin, architectural critic, historian and campaigner; if you don’t, come to think of it, you might have heard of him, too. His last article for Country Life (November 8, 2017), one of his best, explored the ways other nations commemorated their war dead. He was a brilliant historian of world war, a fierce pacifist who knew everything about remembrance and its forms.

He was the voice of Piloti in Private Eye, too, skewering the ugly, the gimcrack and the insincere. In thrall to no one, he raged with all the barbs at his command against the destruction of our past through carelessness and greed. He despised the rich when they tried building on the cheap, whether they were a university college or a developer; he tilted at powerful interests and lobbies and people who, perfectly law-abiding in private life, were prepared to skirt the edges of the law in the pursuit of profit.

His campaigning stopped all our iconic red telephone boxes from being grubbed up and restored ‘Greek’ Thomson to the Glasgow pantheon and the nation. He loved all our great cities: their buildings preserved our story as a people and he sought to defend them from ugliness and wanton loss.

A funeral service wants to accomplish so much: remembrance, gratitude, grief and the life. This one was brilliantly conceived. Crammed with Fleet Street editors and old students, luminaries of conservation and the media, it ended up being more than the sum of its parts, with readings from Betjeman and Blake, Jonathan Meades’s splendid fierce eulogy and sunlight slanting through the stained-glass windows that Gavin had photographed the day before his death.

After, we went to the pub – Gavin also wrote about pubs. I fell in with Liz Davidson, who’s master-minding the restoration of the Glasgow School of Art, which has revealed lost elements of Rennie Mackintosh’s design. ‘You and your wife came to Gavin’s talk in Glasgow,’ she said, suddenly. ‘Years ago, when Gavin was teaching at the Mac. You brought your dog. A lurcher?’

‘Oh dear,’ I said, remembering. ‘Dorrit. She went everywhere with us in those days.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

‘Don’t worry,’ Liz said. ‘At one point, we were stunned by the contemplation of the Thiepval Memorial and all the deaths that lay behind it. Almost in tears. Even Gavin’s voice cracked – and your dog lifted her head at the back of the hall and gave the most mournful howl. It was perfect.’

I’d forgotten. Memories fade. Gavin was right: buildings outlive us all and they’re each memorials. They should not be allowed to disappear.

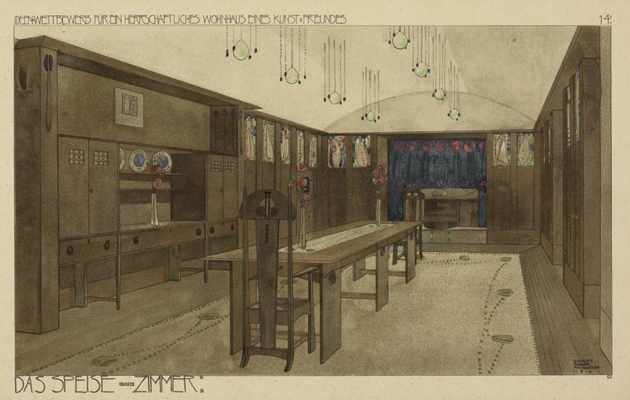

Exhibition review: Mackintosh Architecture at RIBA, London

Gavin Stamp explores a show of Charles Rennie Mackintosh designs.

Gothic for the Steam Age: An illustrated biography of George Gilbert Scott by Gavin Stamp

John Goodall is impressed by this concise and beautifully illustrated account of Scott's achievements.

The saving of Mount Grace Priory: A ruin revived in Arts-and-Crafts style

The saving of Mount Grace Priory in North Yorkshire is a fascinating tale of far-sightedness, persistence and determination. Gavin Stamp