'Of all the countries in the world, Ireland is the country for ruins'

Jonathan Self muses on the abandoned, forgotten and mislaid objects which dot his surrounds.

On one of my regular walks, I pass a ruined tower house that bizarrely, although windowless, still has a solid oak door. It is my occasional habit (I concede it is a little eccentric, but it brings me pleasure) to stop and, having checked that I am alone, recite a few lines from The Listeners, complete with knocking and smoting. Anyway, yesterday, I had just got to: ‘And a bird flew up out of the turret,/Above the Traveller’s head’, when I felt something brush against my leg and, after returning to earth (I am a jumpy soul), I perceived a small tabby kitten. Far too clean and well fed to be wild, far too far from the nearest farm to have got itself lost, I recognised the poor little thing for what it was: an unwanted Christmas present that had been driven out to the countryside and abandoned. It was in the right place. The landscape around here is knee deep in abandoned items.

Offhand, I can think of a huge, half-built yacht in a field, several rusty tractors, a megalithic stone circle, various bits of redundant agricultural equipment, a dozen old beehives and a rotting gypsy caravan. This is before I start to list the abandoned buildings. In 1843, a German geographer called Johann Georg Kohl published an account of a trip made to Ireland the previous year. ‘Of all the countries in the world,’ he wrote, ‘Ireland is the country for ruins.’ Not much has changed in 180 years.

Our townland boasts a ruined mine, a ruined school, a ruined mansion, a ruined church, two ruined castles, one ruined hamlet, about a dozen ruined farmhouses and more ruined cottages, barns, byres and sheds than I care to count. In one abandoned house, the dining-room ceiling clearly collapsed onto a fully laid table. Everyone seems to have simply got up and moved elsewhere, for even the napkins are still there. There’s a cottage where the only thing left is a wall of framed family photographs. I imagine a conversation between the last inhabitants as they drove away: ‘I forgot the photographs.’ ‘Will we go back?’ ‘No, it is too late now.’

Some of the abandoned properties are little more than piles of stones. Others, although empty for years, are full of furniture and personal possessions. It is easy to understand why there are so many of them. One hundred years ago, seven out of 10 people lived in the countryside. Today, seven out 10 people live in towns or cities. As Oliver, 18, is fond of saying: ‘Do the math.’ According to Longfellow: ‘All houses wherein men have lived and died,/Are haunted houses.’

Ruins bring us closer to the unseen world, remind us of our mortality, pique our curiosity and stimulate our imagination. Even if they are invariably a result of tragedy — in particular, famine, failure, poverty, or death — there is something irresistible about an abandoned house. When Rose Macaulay wrote The Pleasure of Ruins 70 years ago, she was on to something.

We own an abandoned building ourselves. For the past few months, my wife, Rose, has been renovating a derelict gate lodge, which had fallen into such disrepair that you could see the sky through the ceiling of every room; next month, we will be welcoming a family who has been forced to abandon their own home. The dogs, who, in the space of 24 hours, have made their feelings about the abandoned kitten abundantly clear, are hoping that our new Ukrainian guests will take her in.

Jonathan Self: Don't measure your life in years — measure it in dogs

Jonathan Self celebrates a birthday for a beloved dog.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Credit: Alamy

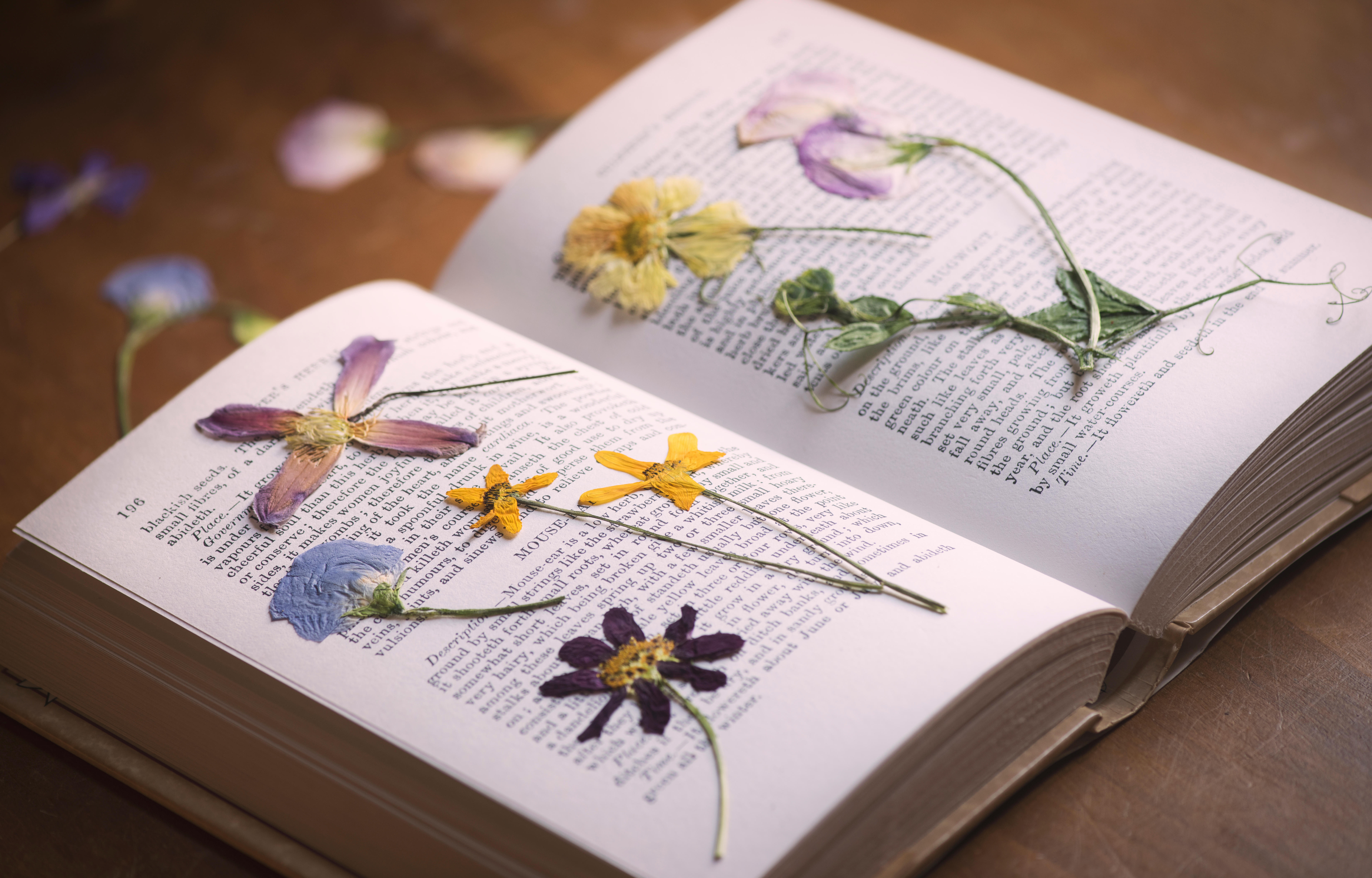

Jonathan Self: The collections that made me, from pressed flowers to my 416 'do not disturb' signs stolen from hotels

Who knew that pressing flowers could be thrilling and skilful? Jonathan Self, a self-confessed 'obsessive collector', tells all.

Jonathan Self: 'In Ireland, summer smells sweet, effervescent and damp. In Tuscany, one almost has to push one’s way through it'

Jonathan Self's recent move to Italy has brought a fresh challenge. Or rather, a hot and heavy one.

Credit: Getty Images

Jonathan Self: 'Ten yards from shore, I felt completely and utterly alone, the last man on earth'

A wintry dip in the ocean revitalises Jonathan Self.

Credit: Alamy

Jonathan Self: 'Town folk know pleasures, country people joys'

Live in a village and you'll live longer, says Jonathan Self — just be prepared for everyone to know your business.

"Hippocrates's advice — 'if you're in a bad mood, go for a walk' — would have me constantly perambulating"

Jonathan Self on the End of the World, ancient battlegrounds and friendly pigs.

After trying various jobs (farmer, hospital orderly, shop assistant, door-to-door salesman, art director, childminder and others beside) Jonathan Self became a writer. His work has appeared in a wide selection of publications including Country Life, Vanity Fair, You Magazine, The Guardian, The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph.