Jonathan Self: The collections that made me, from pressed flowers to my 416 'do not disturb' signs stolen from hotels

Who knew that pressing flowers could be thrilling and skilful? Jonathan Self, a self-confessed 'obsessive collector', tells all.

‘It is good to collect things,’ said Anatole France, ‘but it is better to go for walks.’

I’ve been doing both.

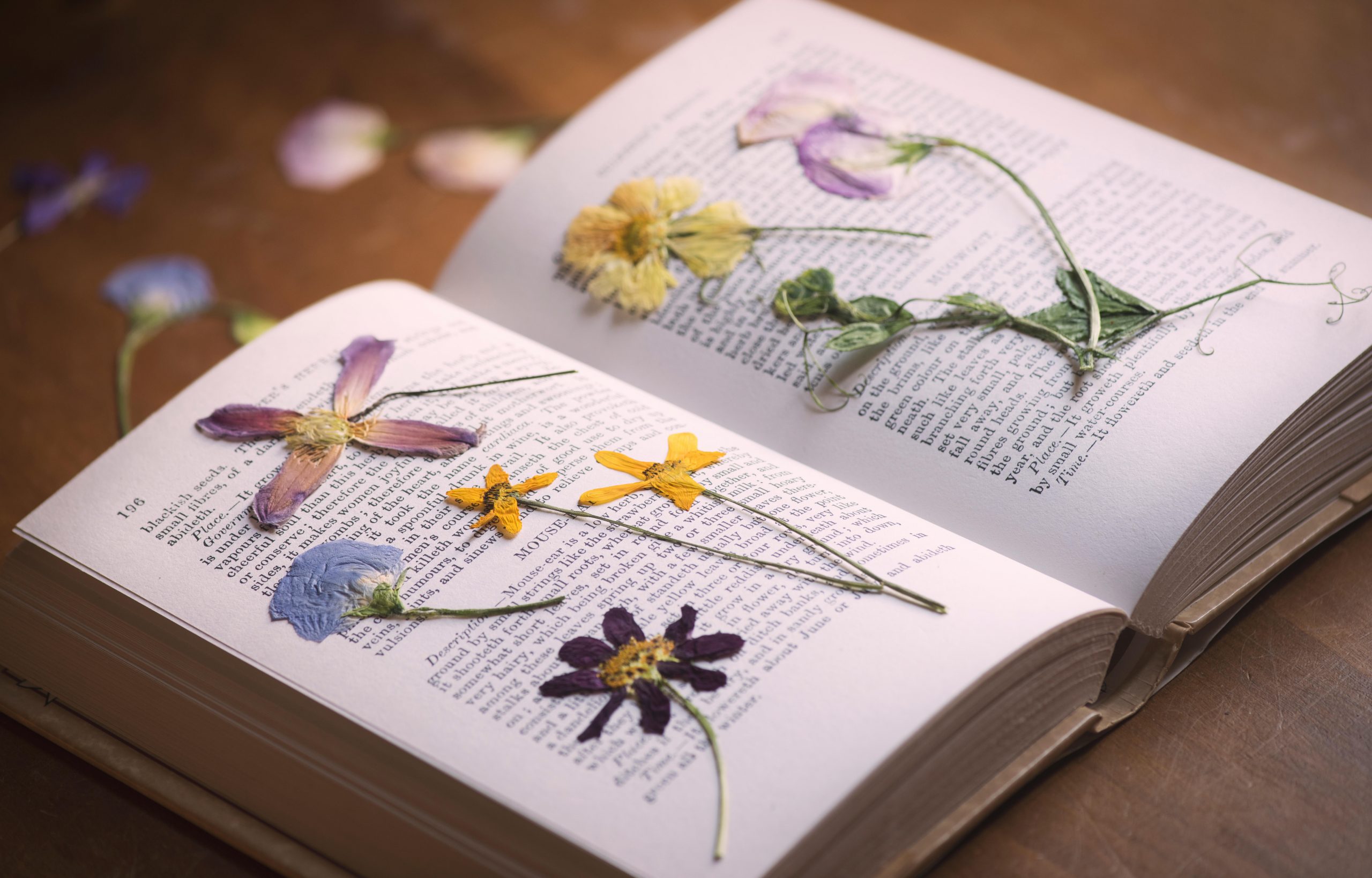

Fed up with the same daily walk since the first lockdown, I decided, in January, that I would make it more interesting by picking and pressing a single example of every wildflower I spotted on my route over the course of the year. All terribly Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady, I know, but it turns out to be a surprisingly engaging hobby. To begin with, there is — as it were — the thrill of the chase. I am currently gloating over what I think (hope) is a green-winged orchid, discovered in a field of cows, which is as rare as it is beautiful (the orchid, not the field of cows).

Anyway, searching for specimens has helped me to rediscover what had become an all-too-familiar landscape. I have also developed new skills — carefully cutting only one specimen, identifying plants and preserving them is a trickier business than I had ever imagined — plus there is the satisfaction of mounting each exhibit in a special album purchased for the purpose, at great expense, from a store I don’t care to advertise (oh, all right, Smythson). Never mind the etchings, future visitors to the Self residence will be invited to come up and see my dried flowers.

"The worth of a collection should not be measured solely in terms of its monetary value"

I have always been a somewhat obsessive collector. I am not quite as bad as P. G. Wodehouse’s fictional millionaire J. Preston Peters, who ‘came to love his scarabs with that love surpassing the love of women, which only collectors know’, but I understand what Sara Teasdale meant when she wrote:

Spend all you have for loveliness, Buy it, and never count the cost.

At the moment, I am actively searching for anything by the Victorian jeweller E. W. Streeter; paintings by the East Anglian artist Harry Becker; antique amulets (present objective a Viking, gold-mounted elf shot, which protects the wearer from invisible arrows fired by elves — how useful is that?); books with amusing titles (recent finds include The Manly Art of Knitting, The Practical Pyromaniac and Fancy Coffins to Make Yourself); and old photographs of people with their dogs.

Space does not allow a description of past infatuations (416 ‘Do Not Disturb’ hotel signs, anyone?) or future manias. Indeed, I have just purchased an exquisite medieval encaustic tile, which may or may not lead to further acquisitions, although whenever I have one of something, I can’t help thinking of a snatch of dialogue from the Father Ted series in which Dougal says: ‘Ted, could you pass me my record collection?’ To which Ted replies: ‘Okay, here it is. Oh, and Dougal, you need more than one record for a collection. What you have is a record.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

I feel I am in good company, at any rate. Wasn’t Noah, after all, the first ever collector, having been instructed to gather ‘of every living thing of flesh, two of every sort’?

My own collecting hero has always been J. Paul Getty, who was authorising purchases for his museum on his deathbed. In 1965, he wrote a short, but inspirational book called The Joys of Collecting, in which he waxes lyrical about hunting for pieces to add to one’s collection, the research process and the fact that the true collector does not acquire objects for himself, but in order to share them with others.

Crucially, he points out that the worth of a collection should not be measured solely in terms of its monetary value. Turning the pages of my beloved dried-flower album, I can vouch for the truth of this.

Credit: Le Chameau

Best walking boots for women, from walks in the woods to hiking the Himalayas

Whether you are planning a long country walk or a gentle stroll on a well-beaten path, make the most of

A Great British holiday on wheels? What it's like spending four days in a Ford Nugget campervan

The boom in British holidays has brought a boom in the number of people getting campervans such as the Ford

Jonathan Self: Don't measure your life in years — measure it in dogs

Jonathan Self celebrates a birthday for a beloved dog.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

Jonathan Self: Our postman delivers 1,000 items a week — and less than 50 are 'real' letters

Jonathan Self laments the fact that we're losing the art of writing letters.

After trying various jobs (farmer, hospital orderly, shop assistant, door-to-door salesman, art director, childminder and others beside) Jonathan Self became a writer. His work has appeared in a wide selection of publications including Country Life, Vanity Fair, You Magazine, The Guardian, The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph.