'Russia must be isolated. Utterly walled off,' said the Russian. 'When Putin falls, the new regime will be the same as the old'

Jason Goodwin heads east and meets an exiled Russian with an eye-opening perspective.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I went to Tallinn for the Estonian Literary Festival, to interview the Finnish crime writer Leena Lehtolainen and the Welshman Philip Gwynne Jones, who writes murder mysteries in Venice. It was very international, but there was only one country we were all thinking about. Space was made for a formal discussion between an investigative journalist, a Russian exile and an Estonian MP.

‘Russia,’ the Russian said, ‘must be isolated. Utterly walled off. Let the world forget Russia.’ There was no murmur of protest, so he continued: ‘The state must be declared rogue, a terrorist organisation. You don’t deal with it. Because when Putin falls, and he will, the new regime will be the same as the old one, with another figurehead.’

Russia missed its chance to change in the 1990s and what the Estonian MP called the ‘Chekist state’ would rule Russia forever; the people are too miserable, poor and ill-educated to protest.

On my way home, I changed planes and, on each flight, I sat next to an architect. The American specialised in house renovations for the super-rich, stipulating every detail, down to their cars, their cutlery and their bread.

Natasha lived in Switzerland, where she specialised in historic-building conservation, mostly churches. In one hand, she held a miniature bottle of Vana Tallinn, the Estonian liqueur; with the other, the arm rest. I explained that aeroplane wings are built as a single piece running through the fuselage, information I have found reassuring. She thanked me and screamed gently when we lurched on take-off. ‘I prefer trains,’ she said.

"She became a librarian, in a world that could have been devised by a satirist like Gogol"

She had just made a difficult journey to St Petersburg to see her father, a prominent art critic who had been married four times and had scores of girlfriends; he was a charmer, a dancer on tables, juggler of epigrams and vodka shots. ‘All the women in the family told me I must come now, to see him,’ Natasha explained, ‘because he is very ill.’

She flew first to Helsinki and then found a private car taking passengers to St Petersburg. ‘On the way back, I took a bus to the Estonian border and I walked across the border carrying my bags. But he was not actually so ill.’

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Natasha grew up surrounded by books, not least because of her grandmother, who enlisted at the age of 15 and spent five years of the Second World War under arms. When the war ended, she found herself on the far side of the Donbas, on the edge of the Caucasus, and settled down with an army veteran who gave her a daughter and then died of his wounds. She became a librarian, in a world that could have been devised by a satirist like Gogol. By order of the Five-Year Plan and the central distribution committee, books written in Russian, approved in Moscow and printed in Cyrillic were distributed to every Soviet republic, whether there were any readers of Russian to enjoy them or not. Every month, Natasha’s grandmother travelled through the Turkic-speaking regions where nobody read Russian, the so-called ‘Stans’, buying up unwanted books to bring back to Russian-speaking republics where people might actually read them. She was, in a sense, built into the Plan.

It seemed superfluous to discuss the war, and when conversation veered in that direction Natasha’s eyes filled with tears. We began to descend bumpily through the clouds. Natasha gave me a weak smile and knocked back a shot of Vana Tallinn.

Russia, I thought, is not a place one can easily forget.

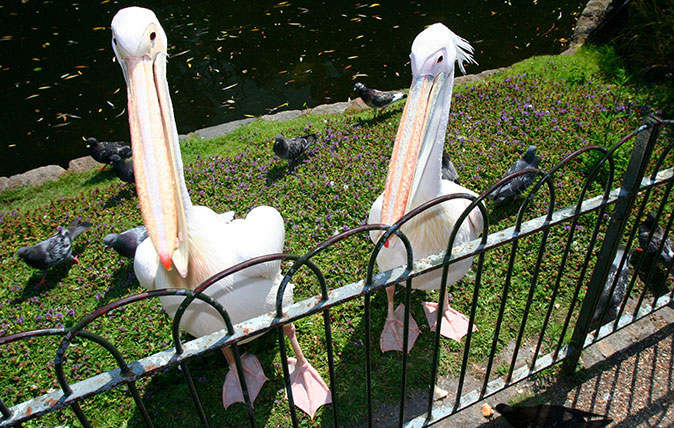

How the St James's Park pelicans sparked a Cold War stand-off between Russia and the USA

Former diplomat Alistair Kerr tells the strange tale of the pelicans that live in the centre of London – and how

The real-life farm and animals that give life to George Orwell's Animal Farm

It's 75 years since George Orwell published Animal Farm, and while the book is an allegory based on Soviet Russia