It shouldn't happen at a coronation: A brief history of crowning day disasters

Things don’t always go to plan at a coronation, from stumbling peers to muddled clergy, dripping candles and even earthquakes, reveals Carla Passino.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Being in touch with the people is a useful talent for a monarch, and it's a skill that William IV had. With little liking for pomp and circumstance, and coming to the throne in difficult economic times, William considered ‘whether the Coronation could not be dispensed with’ altogether, according to Arthur Penrhyn Stanley’s Historical Memorials of Westminster Abbey; when told it could not, he put on a ceremony that cost £42,298 3s. 9d — less than George IV splurged on his robes and banquet alone. It was dubbed the ‘The Half-Crownation’ by bitter MPs expecting more of a show, but the wider public loved the King’s frugality, everything went well, and it entered the history books as a great success.

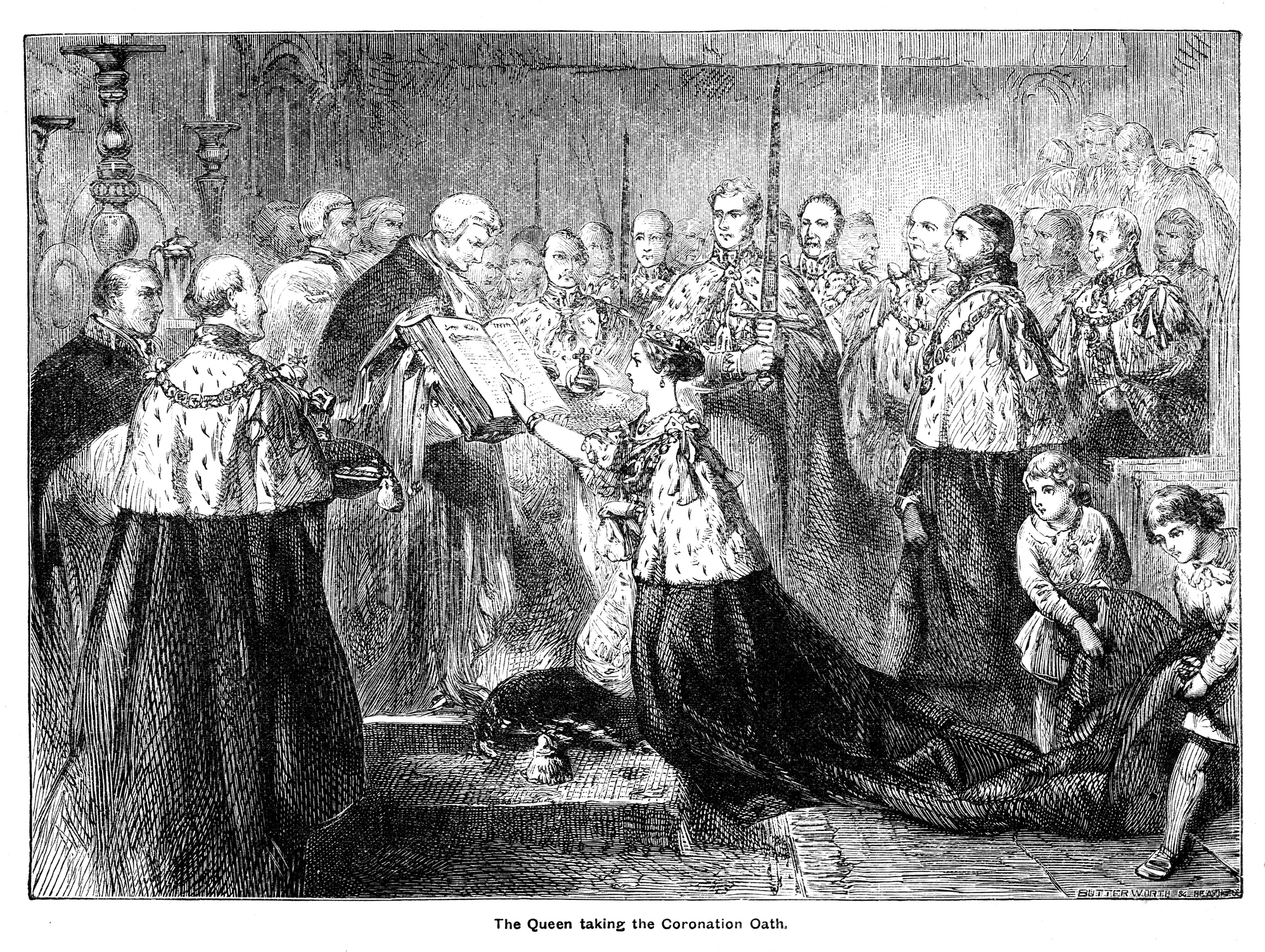

Other monarchs haven't been so lucky. Queen Victoria's coronation was marred by John, 1st Baron Rolle, who took a tumble during the supreme moment. But the elderly peer might have been relieved to discover that his mighty tumble was hardly the only blunder to take place at a coronation.

In fact, while Britain is great at pageantry, its most meticulously-planned ceremony has so often been riddled with mishaps that they have almost become a tradition in their own right. Here are some of the most extraordinary.

William the Conqueror: Fire at Westminster Abbey

It all started with William the Conqueror and a misunderstanding. It was Christmas Day in 1066 and the King was about to be crowned. Asked whether William should take the crown of England, Norman and Anglo-Saxon notables roared their assent in their respective languages — but the soldiers stationed outside Westminster Abbey took the din for a sign of English betrayal and set fire to some houses nearby.

A tumult ensued and many involved in the service fled. Only a handful of ecclesiastical officials kept their cool as Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, crowned a fearful William amid the flames.

Henry III's lost jewels

Thankfully, most other coronation debacles weren’t quite as tragic (with the exception of the massacre of Jewish people that marred Richard the Lionheart’s crowning). Nine-year-old Henry III had to put up with wearing one of his mother’s corollas at Gloucester Cathedral in 1216, because most of the royal jewels had been lost, probably in a bog, when his father, John, fled his barons’ rebellion. It clearly didn’t do Henry any harm: he went on to become medieval Britain’s longest-reigning king.

Richard II's bedtime

Another boy king, Richard II, wasn’t so lucky. The courtiers planning his coronation in 1377 vastly overestimated the endurance of a 10 year old — according to late-medieval chronicler Thomas Walsingham’s Historia Anglicana, the King was so exhausted by the end of the proceedings that he was carried ‘in humeris militum’ (on the soldiers’ shoulders) to his chamber so that he could muster enough energy to attend the banquet.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Not that the courtiers minded when, as Walsingham reports, in the middle of the Royal Palace stood a hollow marble column topped by a gilded eagle, from the feet of which ‘wines of different kinds flew for the entire Coronation day’. Richard II perhaps ought to have taken his fatigue as an ill omen: quickly becoming an unpopular monarch, he was eventually deposed by Henry of Bolingbroke.

Charles I's coronation earthquake

When it comes to portents, nothing beats Charles I’s coronation: from the tainted Archbishop of Canterbury, who had killed a gamekeeper in a hunting accident, to the earthquake that shook the ground during the ceremony via the left wing of the dove that broke off the sceptre staff, it was a catalogue of disasters. Even Charles didn’t help himself by breaking with tradition and choosing to wear white satin instead of the customary purple. The only redeeming quality of the day was that ‘it was one of the most punctual Coronations since the Conquest,’ according to Charles MacFarlane’s Cabinet History of England. There have been greater feats.

James II's wobbly crown

Not many Stuart kings enjoyed hitch-free coronations — notably James II, whose crown refused to sit properly on his head.

Removing his gigantic wig would have probably done the trick, but constituted a fashion crime, so he put up with wobbly headgear instead.

George III's crown-undrum

What to do with the crown also troubled George III, albeit for different reasons. Should he take it off to receive Holy Communion? He quizzed the Archbishop, who, in turn, asked the Bishop of Rochester, ‘but neither of them could say what had been the usual form,’ according to the Gentleman’s Magazine.

As party planners go, George III’s were appalling: apart from being evidently uninformed on matters of Royal Communion etiquette, ‘in the morning they had forgot the sword of state, the chairs for the King and Queen and their canopies,’ that old busybody Horace Walpole noted in a letter. ‘They used the Lord Mayor’s for the first and made the last in the Hall.’

George I's Latin lesson

Despite all that, George III’s coronation was less awkward than that of his grandfather, George I, in 1714. Fresh from Hanover, the King spoke as much English as his new Court spoke German: nil. Cleverly, one bright spark saved the day by celebrating the service in Latin — thereby ensuring that no one understood anything.

George IV 'forgets' to invite his own wife... and Karma delivers him a catalogue of disasters

The most disastrous coronation was, by far, George IV’s. The King detested his wife, Caroline of Brunswick, to such an extent that he refused to have her crowned alongside him and even banned her from the service.

Determined to attend, she arrived in full regalia, only to find all the doors closed and Sir Robert Inglis awaiting with an unequivocal message: ‘It is my duty to inform you that there is no place provided for your Majesty in the Abbey.’

Whether by coincidence or instant karma, however, the ceremony was also an ordeal for George IV. Already struggling with the heat of the day before he entered Westminster Abbey — which, having been lit by more than 2,000 candles, was not cool, either — the monarch was soon close to overheating.

Swathed in gold and velvet clothes that made him look like ‘some gorgeous bird of the east’, according to Benjamin Haydn, the King was found — in the words of a 19th-century Dean of Westminster, Arthur Penrhyn Stanley — ‘cooling himself, stripped of all robes, in the Confessor’s Chapel and, at another part of the service, was only revived by smelling salts’.

The rest of the congregation was feeling the heat, too, ‘for occasionally large pieces of melted wax fell, without distinction of persons, upon all within reach’. The ladies’ hair ‘lost all traces of the friseur’s skill long before the ceremony was concluded’ and the choir, possibly outdone by the suffocating temperature, left too early.

When the King headed to Westminster Hall, the Barons of Cinque Ports, who were meant to bear the canopy over his head, visibly shook. Conscious that getting tangled in silk, however richly embroidered, was perhaps not the best way to mark his coronation, George IV found a fresh spring in his usually plodding step and hastened ahead — but the Barons, determined to do their job, tottered behind him, the massive canopy swaying ever more perilously close to the King.

No wonder that, when he arrived at the hall, ‘his Majesty was evidently fatigued’, according to A Brief Account of the Coronation of His Majesty George IV published by D. Walther in 1821. The booklet also reports that those present ‘never saw him in better spirits’, but, when later recalling his coronation, he’s said to have muttered: ‘I would not endure again the sufferings of that day for another kingdom!’

Queen Victoria's

It’s a feeling his niece Victoria must have shared and not merely because of poor Lord Rolle’s unfortunate accident or the Duke of Wellington’s social faux pas of exposing his boots when he descended the steps from the throne after swearing allegiance. The Queen had a more ‘gripping’ problem. Goldsmiths Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, had made a coronation ring to fit her pinky, but it was meant to fit her ring finger.

The Archbishop forced it on anyway, so poor Victoria not only had to soldier through the day with a pinched digit, but also ‘had the greatest difficulty’ in prising the ring off and eventually only managed ‘with great pain,’ as she noted in her diary.

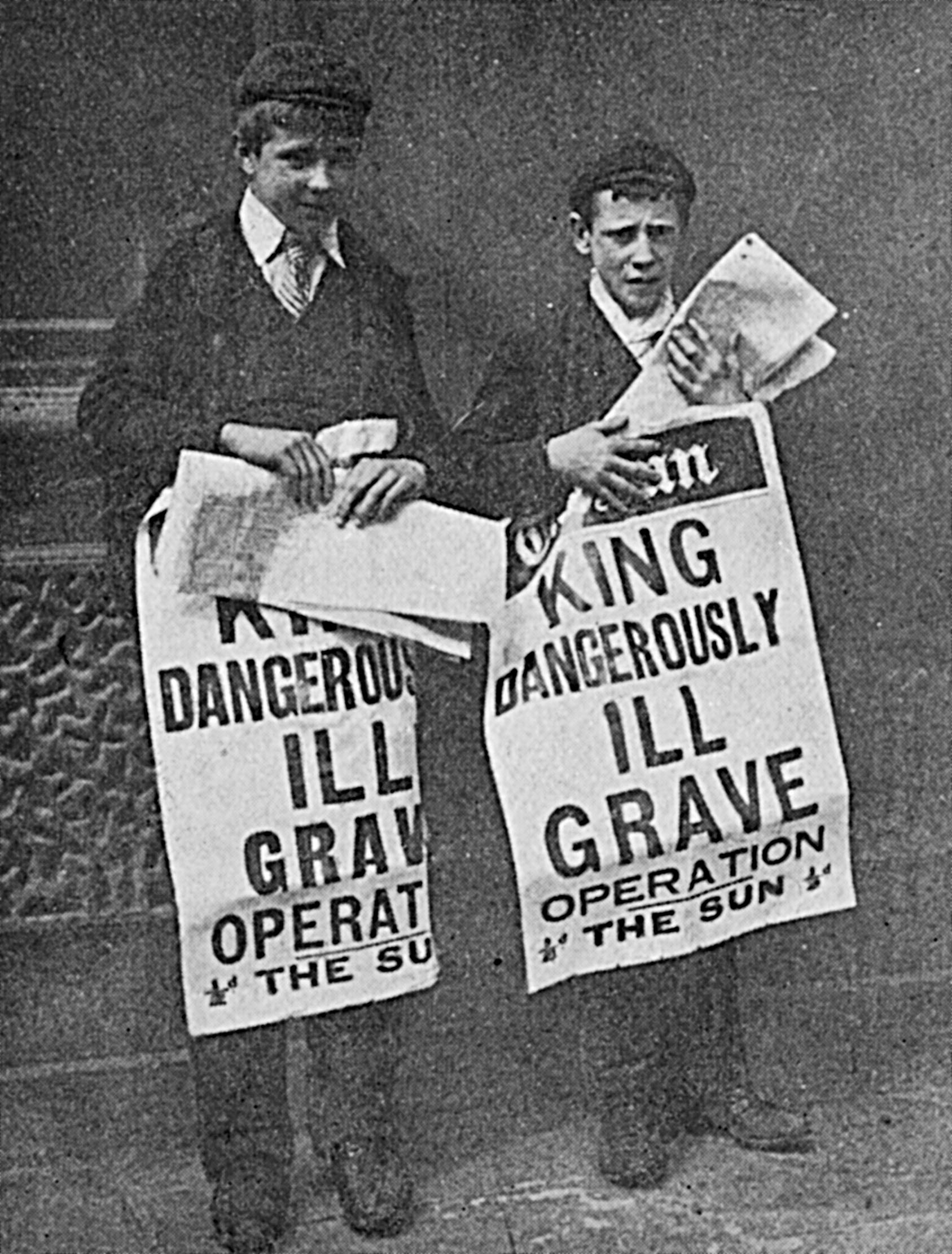

Edward VII's surgical excuse for postponing his own coronation

A sore finger was nothing to the pain suffered by Victoria's son, Edward VII, who came down with appendicitis two days before his big day on June 26, 1902. The event had to be postponed to August so the King could undergo surgery.

Despite the extra practice time, on the day itself, the ancient Archbishop of Canterbury, who was almost blind, still put the crown on the King’s head the wrong way around.

The coronation that wasn't — until it was, with a last-minute change of King

More than 30 years after they had had to make do with a delayed coronation, the British were treated to another surprise ceremony when Edward VIII abdicated after less than a year on the throne, eventually delivering a farewell address rather than a coronation speech.

With preparations already under way for his crowning in May 1937, his brother, George VI, decided it made no sense to start anew: ‘Same date, different king,’ he is said to have quipped.

The day itself was hardly flawless — the elderly Dean of Westminster fell and nearly sent the crown flying, the Archbishop of Canterbury struggled to place it on George VI’s head and a bishop stepped on the King’s train, not to mention the fact that the lengthy service induced several peers to seek solace in the arms of Morpheus.

However, this can hardly have mattered to a man that rose and met his greatest challenge: speaking in public. ‘Not a moment’s hesitation or mistake!’ the King reported triumphantly to his speech therapist in a letter that was unearthed a few years ago.

Queen Elizabeth II's freezing June

George VI's daughter — Elizabeth II — also suffered at her coronation, and was the meteorologists who got it sorely wrong. They had suggested June 2 as the perfect date because, statistically, it was the day most likely to have sunshine.

It turned out to be so drizzly and cold that the Royal Mews staff had to tuck a hot-water bottle in the Queen’s carriage to keep her warm.

At least Elizabeth II’s ceremony went without a glitch; here’s hoping the same holds true for Charles III.

What the Charles III coronation invitations look like — and why they'll likely be worth a fortune one day

Invitations to coronations have always been highly prized. Since the 18th century, they have also been designed to reflect the

The Timetable for the Coronation of King Charles III, including the order of service and The Oath

Eleanor Doughty takes a look at what's happening over coronation weekend — and explains the changes in the roles of dukes

What sort of man is King Charles III, and what sort of king will he be?

A brilliant conversationalist, a cracking host and, surprisingly, an excellent actor, Charles III genuinely cares for people and strives to

Sir John Major on King Charles III: 'The King was so far ahead of received wisdom that he had to wait for it to catch up'

Ahead of the curve, diligent and gifted with an empathy that allows him to connect with all people, Charles III

Camilla, the Queen Consort: The 'best listener in the world' and the King's secret weapon

Whether she’s highlighting domestic abuse, championing literacy, dining with pensioners or quietly supporting her husband, our new Queen is excelling

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.