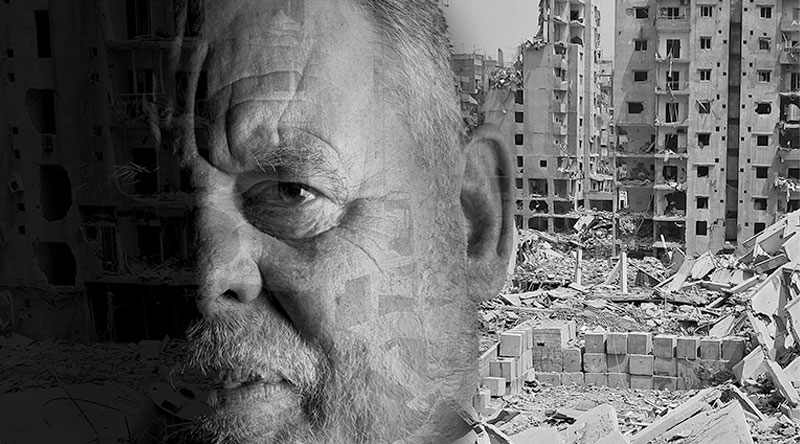

Terry Waite: 'I was captured myself. To be frank, I wasn’t surprised.'

On the 25th anniversary of his release, former hostage Terry Waite looks back on his work, his years in captivity, and how the BBC World Service saved his life.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It was January 1971 and I was travelling with my wife and three small children back to our home in Kampala, Uganda, after a brief holiday in Kenya. The previous weeks had been stressful to say the least. The Ugandan army appeared to have a licence to do exactly as it wished and violent robberies throughout the city were commonplace. We ourselves had almost lost our lives on two occasions when we were held up at gunpoint and lost our car on both occasions.

We approached the border post expecting the usual harassment travellers were subject to, but, to our surprise, there was no one on duty.

We sailed through the open barrier and were soon home.

Early the next morning, we heard gunfire. This was nothing exceptional and we ignored it. I then turned on the radio to get the early-morning news from the World Service of the BBC to be greeted with the announcement: ‘There has been a coup in Uganda. Milton Obote has been overthrown, and General Idi Amin has taken command.’

Once again, the World Service was ahead of the game.

It was my habit, from when I first started on my international travels, always to take with me a shortwave radio to receive the World Service. Today, I pack my iPad, but, long before computers were commonplace, a small radio receiver was an essential part of my travelling kit.

It was undoubtedly true that no other international broadcaster could hold a candle to the World Service for accuracy and balanced reporting. The tune Lilliburlero rang out across the world and one instantly knew that one was tuned into London, not Moscow or the Voice of America.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Today, that tune is only played infrequently, but it was an important distinguishing signal, especially when one was tuning in from an area where reception was far from adequate.

Then, the BBC maintained a string of repeater stations across the world to boost the shortwave transmissions and, during my travels, I would often visit them for a chat with the staff who manned them. Although the World Service was an invaluable source of information, little did I realise in those days how much it would come to mean to me.

For a number of years, I was active in the field of hostage negotiation in Iran, Libya and Beirut, to mention but a few of the places where I was a frequent visitor. Once I was in situ, I was on my own. Telephone communications were out of the question and local radio stations were often less than impartial in their presentation of the news. However, shortwave covered most of the world and I could usually tune in to the World Service without difficulty.

I also appreciated the fact that, although there was a bias in favour of news reporting, there was an attempt to bring some balance to the listeners by broadcasting concerts, plays, quiz programmes and news about Britain. No apology was made for the fact that the BBC was transmitting something of the British way of life.

Let’s skip forwards a few years. After gaining the release of hostages from several parts of the world, the virtually inevitable happened and I was captured myself.

To be frank, I wasn’t surprised. If one decides to do what is a very dangerous job, then one is a fool not to take into account the fact that one may be captured or, indeed, killed. If that happens, then one takes personal responsibility.

Nobody made me do what I did. It was my free choice to work for the release of innocent captives and, when things went badly wrong, all one could do was to make the best of a difficult situation.

For almost five years, I was kept in total solitary confinement. I was chained by the hands and feet to the wall and had no books or papers or contact with the outside world for much of that time.

When anyone came in the room, I had to pull a blindfold over my eyes, so I had no real contact with another human being. To say the least, it was austere.

I knew that there were captives in the room next to where I was kept and, for almost four years, I tapped out my name on the wall using a laborious code— one tap for A, two for B and so on. (I soon started to regret that my name was Terry Waite.) Finally, after years of effort, I heard the taps from the other side of the wall and the names of John McCarthy and Terry Anderson were distinguishable.

Much later, when we all met in freedom, I learned that they had been unable to respond to me until one of the group was moved and chained to the wall on which I was tapping and could thus reply.

They had a radio—something which I didn’t—and they tapped out news from the World Service: the end of apartheid, the fall of the Berlin Wall and, more importantly to me at that moment, news that my family was well. My cousin, John Waite, himself a broadcaster on Radio 4, sent short messages over the World Service with the hope that they might get to me. They did, but not quite in the way he expected.

All the captives in that unusual relay station said that, although they tuned in to all the international broadcasters, it was the World Service they trusted most of all. In the final weeks of captivity, I, too, was allowed to have a small radio and was delighted to discover that the World Service was broadcasting to Beirut virtually 24 hours a day.

I will never forget balancing the small set on the iron bar to which my chains were secured and tuning in for the first time. It was the first night of the Proms and Elgar was being played.

That music, so evocative of my home country, was the first I had heard for years and it meant so much to me. What a shame that music is no longer a part of the World Service programming.

Alas, recent years have seen dramatic changes at the BBC and balanced broadcasting by the World Service has virtually gone out of the window.

It was a sad day for me when I heard that the service, based for so long at Bush House, was to be changed dramatically. The whole operation was to be transferred to Broadcasting House and would become more intimately related to domestic news broadcasting.

International broadcasting is very different thing; the old Bush House had a team spirit, with a culture that was highly professional and, without a doubt, was a world leader. I owe it a great deal.

It was, truly, a lifesaver.

Terry Waite

https://youtu.be/uUl1BaKGNt4?t=10s

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.