Curious Questions: Who invented the jelly cube?

Once a sweet treat fit for the Royal Court, jelly was transformed into a favourite dessert of the masses by the launch of Rowntree’s concentrated jelly cubes. Harry Pearson tells their tale.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

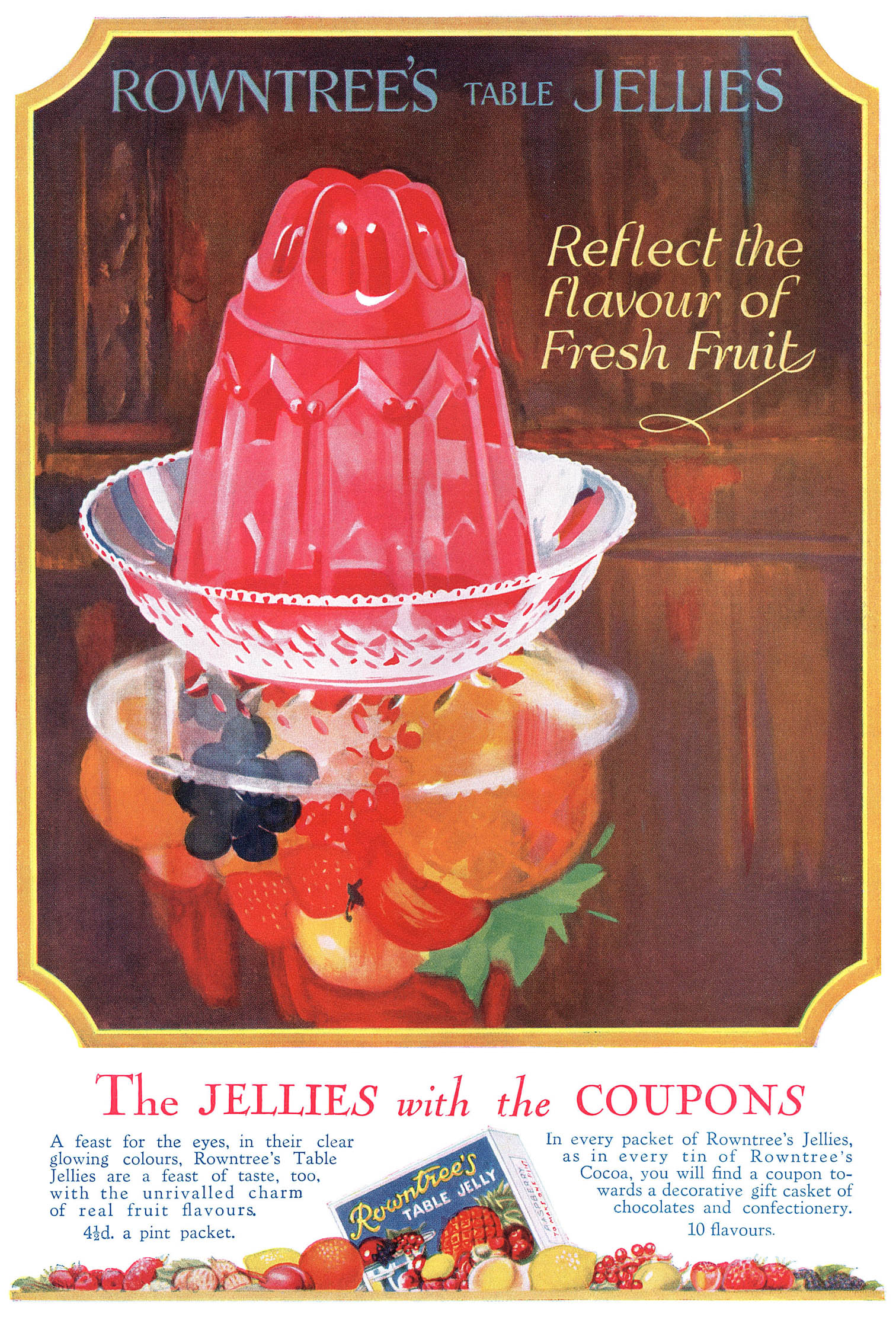

Ninety years ago, Rowntree’s of York launched the world’s first concentrated jelly cubes. Available in 10 tantalising flavours (such as pineapple, vanilla and greengage), they dissolved in half the time of any rival. The year 1932 also saw the publication of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and these magic cubes, which allowed the preparation of a ‘thrilling’ dessert in a mere 80 seconds, might have sprung from the pages of his novel, as a glistening, fruity glimpse of mankind’s future.

Rowntree’s ‘cube-moulded’ instant jelly was the final stage of the quivering pudding’s slow procession from the palaces of the Pharaohs, via royal wedding feasts, to the paper bowls of a million children’s parties. The rubbery squares would carry jelly to the very peak of popularity, only to see sales shiver and collapse under a remorseless onslaught from ice cream and yoghurt.

Although Britain’s relationship with jelly dates back to Anglo-Saxon times, the idea of serving it as a sweetmeat arrived in the Middle Ages, when refined meat jelly — often made from pig’s ears — was flavoured and coloured with saffron, cochineal or the juice of pressed violets.

By the Renaissance, gelatine for desserts was being made largely by boiling either calves’ feet or shavings of hartshorn — the antlers of young male deer (alternatives included isinglass, obtained from the swim bladders of fish, and, later, arrowroot imported from the West Indies). The fact that gelatine was the boiled reduction of meat led early medical scientists to conclude that, under extreme emotion, people might literally be reduced to jelly. In Hamlet, Shakespeare tells us that the sight of the King’s ghost has ‘distll’d’ the watchmen ‘almost to jelly with the act of fear’.

In the beginning, jelly was only for the wealthy elite. Straining and skimming the liquid until it was clear and flavourless was a laborious task that took days, rather than hours. The sugar used to sweeten it, together with the spices — cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and coriander — required to flavour the pudding, were eye-wateringly expensive, too, so much so that serving it was a sign of both the status of the household and the esteem in which hosts held their visitors.

When the Embassy of Spain arrived in England in 1517, Henry VIII arranged a lavish banquet at which 20 different jellies — including the King’s favourite, flavoured with rosewater — were served. The glimmering array dazzled one visitor, Francesco Chiericarti, who observed that the jellies ‘were made in the shapes of castles and animals… as beautiful as can be imagined’.

By Georgian times, jelly had become extremely fashionable in England, when the jelly houses in London’s St James’s — such as Tomlin’s and Kelsay’s — were the 18th-century equivalent of an exclusive modern cocktail bar. In their gilded interiors, wealthy young rakes who aspired to be Lord Byron gobbled jellies from cut-glass goblets. Indeed, Kelsay’s, located opposite St James’s Palace, was so en vogue that it featured in the satirical cartoons of James Gillray.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

However, jelly’s enviable exclusivity was challenged in the early years of Queen Victoria’s reign, when J. & G. Company of Edinburgh launched the world’s first industrially produced powdered gelatine. This and the development of pneumatic presses, which could produce hundreds of copper jelly moulds per day, helped propel the jelly into middle-class homes. At the Great Exhibition of 1851, visitors to the refreshment rooms of Crystal Palace were served jellies in five different flavours, made using instant gelatine and pressed copper moulds, where the treats were hailed as irrefutable proof of British ingenuity and industrial progress.

Copper moulds came in myriad shapes, from lions, ziggurats and hedgehogs to domed temples, salmon and pyramids. Among the most fashionable were those that mimicked London’s latest sensation, Cleopatra’s Needle. Many were made of multiple parts, fastened with pins. Temple & Reynolds of Belgravia produced one of the most elaborate — a copper outer with six spiralled pewter liners, which could be screwed out once the surrounding jelly had set, before the hollows were filled with fruit or flavoured creams. The resulting jelly — known as The Belgrave — looked like the mountain palace of some capricious European monarch. Even more extraordinary were the moulds made by Benham & Froud for the wedding of Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess Alexandra of Denmark in 1863. The emblems of the Star and Garter and the Brunswick Cross ran through them like the name of a seaside resort through a stick of rock.

Although mould-makers and cooks fought to outdo one another, the nature of jelly precluded things from getting out of hand. Few jelly moulds stand taller than 5in in height, as jelly is a slave to gravity and, once it rises above 6in, it is likely to collapse under its own weight. Nonetheless, the dessert’s quivering vulnerability added a touch of theatrical tension to its arrival at the table. Under the heat of the candlelight that shed the pudding’s jewelled colours across white tablecloths, the jelly might melt and slump, as those of the unfortunate Mr Jorrocks did in R. S. Surtees’s novel Jorrocks’ Jaunts and Jollities.

As well as a splendid pudding, jelly — nutritious and easy to eat — was also viewed as a panacea. In Cranford, Mrs Gaskell writes of Mrs Forrester, whose ‘admirable and digestible’ bread jelly is sent out to the sick of the village, and Florence White tells of a Miss Anstey, whose grandmother would administer her homemade Portwine jelly (made using isinglass and gum Arabic) ‘to an invalid in small teaspoonfuls’.

The first commercial instant jelly — comprising gelatine granules mixed with sugar and fruit flavourings — was invented in 1897 by American Pearle Wait, who stumbled across it when trying to produce a laxative tea. Unfortunately, neither Wait nor the man to whom he sold the Jell-O patent (orator Frank Woodward) could make any headway commercially. After several futile years, Woodward sold his company for only $35. Frustratingly for him, 18 months later and thanks to a cunning advertising campaign that boasted that the unknown pudding was ‘America’s most favourite dessert’, Jell-O sales were worth more than $250,000. By 1904, they’d topped $4 million. If Wait and Woodward ever ate Jell-O again, it must have tasted rather bitter.

In the post-war years, jelly — whether served on its own or as part of a trifle — could justifiably claim to be Britain’s favourite pudding. Yet, the old magic was slowly melting away. Jelly had once been an architectural marvel of the dinner table — now, it was increasingly viewed as infantile and even a little silly. It was seen as the stuff of children’s teas, where, dolloped with tinned cream and sprinkled with hundreds and thousands, it might find itself loaded onto a spoon by William Brown and catapulted into the ringlets of Violet Elizabeth Bott.

The arrival of television further vulgarised poor old jelly, when — on The Benny Hill Show and The Two Ronnies — it became the subject of bawdy comedy. The grand opera of the Victorian era had dissolved into pantomime. It had become the whoopee-cushion of puddings.

On Blackpool Pleasure Beach in 1997, the Army Logistics Corps spent 12 hours building the world’s largest jelly. Measuring 1m (about 3ft) in height and 7m (23ft) wide, it was set using dry-ice machines. Looking back, it is easy to see the emergence of the giant quivering mass from the billowing white clouds as one last gesture of defiance. Three years later, with jelly sales plummeting, the pub-restaurant giant Brewers Fayre announced it was removing jelly from its children’s menu and replacing it with a doughnut.

Thankfully, not everyone has given up on jelly. Heston Blumenthal is a champion of the pudding, food historian and author Peter Brears has headed an annual celebration of jelly at British country houses and gin-and-tonic flavoured jelly has enjoyed a moment in the spotlight. The shimmering British pudding that was marvelled at by foreign dignitaries may never be as popular as it was in its heyday, but its reputation is slowly being restored. We may yet see it return to its rightful position as the most dramatic finale of the celebratory banquet.

Greatest recipes ever: Elderflower and raspberry jelly

Thomasina Miers picks elderflower and raspberry jelly as one of her greatest recipes ever.

The wibbliest, wobbliest auction of the year: 400 jelly moulds and cake tins go under the hammer

A collection of historic jelly moulds and cake tins is up for sale over the next week or so.

Tom Aitken's elderflower and lemon jelly

Make the most of the summer flavours – and put some away for winter.

Harry Pearson is a journalist and author who has twice won the MCC/Cricket Society Book of the Year Prize and has been runner-up for both the William Hill Sports Book of the Year and Thomas Cook/Daily Telegraph Travel Book of the Year.